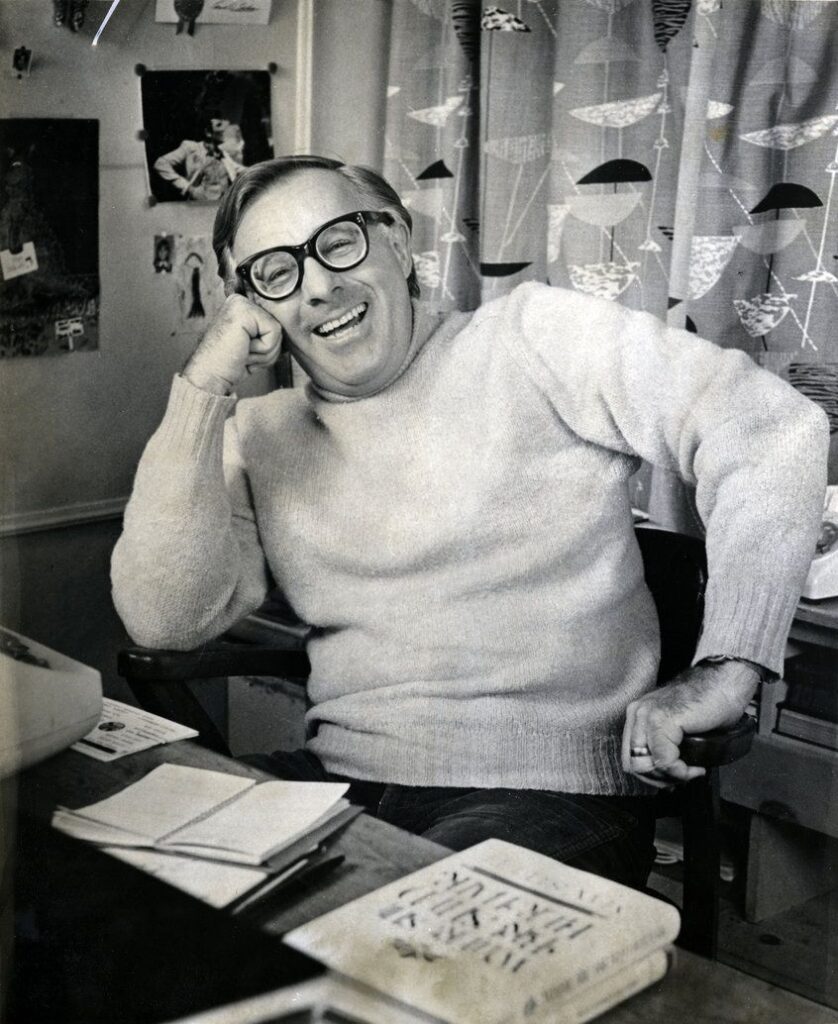

Un-pillow Talk, Ray Bradbury

Un-pillow Talk

‘Good Lord.’

‘Good Lord, indeed!’

They fell back and stared at the ceiling. There was a long pause in which they regained their breath.

‘That was wonderful,’ she said.

‘Wonderful,’ he said.

There was another pause while they examined the ceiling.

Finally she said, ‘Wonderful, but—’

‘What do you mean “but”?’ he said.

‘It was wonderful,’ she said. ‘But now we’ve ruined everything.’

‘Ruined?’

‘Our friendship,’ she said. ‘It was such a great thing and now we’ve lost it.’

‘I don’t believe that,’ he said.

She examined the ceiling in even more detail.

‘Yes,’ she said, ‘it was so marvelous. It went on for a long time. What was it, a year? And now, like damn fools, we’ve killed it.’

‘We weren’t damn fools,’ he said.

‘That’s how I see it. In a moment of weakness.’

‘No, passion,’ he said.

‘No matter how you put it,’ she said, ‘we’ve spoiled everything. How long ago was it? A year? We were great pals, fine buddies, went to the library together, played tennis, drank beer instead of champagne, and now we let one little hour throw it all overboard.’

‘I don’t buy that,’ he said.

‘Think about it,’ she said. ‘Stop and examine the last hour and the last year. You’ve gotta come around to my way of thinking.’

He watched the ceiling to see if he could see there any of the things she had just said.

At last he sighed.

She heard the sigh and said, ‘Does that mean yes, you agree?’

He nodded and she felt the nod.

They both lay on their separate pillows, staring at the ceiling for a long while.

‘How do we get it back?’ she said. ‘It’s so stupid. We’ve known better than this with other people. We’ve seen how things can be killed and yet we went right ahead and killed it. Do you have any ideas? What do we do now?’

‘Get out of bed,’ he said, ‘and have an early breakfast.’

‘That won’t do it,’ she said. ‘Hold still for a while, maybe something will come to us.’

‘But I’m hungry,’ he said.

‘I’m more than hungry, I’m ravenous. For answers, that is.’

‘What are you doing? What’s that sound?’

‘I think I’m crying. What a terrible loss. Yes, I think I’m crying.’

They lay for another long moment and then he stirred.

‘I’ve got a crazy idea,’ he said.

‘What?’

‘If we lie here with our heads on our pillows and look at the ceiling and talk about the last hour and then the last week to see how we led up to this, and then the last month and the whole last year, mightn’t that help?’

‘In what way?’ she said.

‘We’llun-pillow talk,’ he said.

‘Un what?’

‘Un-pillow talk. We’ve heard of pillow talk all our lives, the talk that goes on late at night or early morning. Pillow talk between husbands and wives and lovers. But in this case maybe we can put everything in reverse. If we can talk our way back to where we were last night at ten o’clock, and then at six, and then at noon, maybe somehow we can talk the whole thing away. Un-pillow talk.’

She made the smallest sound of laughter.

‘I guess we could try,’ she said. ‘What do we do?’

‘Well, we’ll just lie very straight and relax and look at the ceiling with our heads on our pillows and we’ll start to talk.’

‘What’s the first thing we talk about?’

‘Shut your eyes and just say anything you want to say.’

‘Butnotabout tonight,’ she said. ‘If we talk about the last hour, we might get into even worse trouble.’

‘Forget the last hour,’ he said, ‘or remember it quickly, and then let’s get back toearlyin the evening.’

She lay very straight and shut her eyes and held her fists at her sides.

‘I think it was the candles,’ she said.

‘The candles?’

‘I shouldn’t have bought them. I shouldn’t have lit them. It was our first candlelit dinner. Not only that, but champagne instead of beer; that was a big mistake.’

‘Candles,’ he said. ‘Champagne. Yeah.’

‘It was late. Usually you go home early. We break it up and get together early mornings to play tennis or to head to the library. But you stayed awfully late and we opened that second bottle of champagne.’

‘No more second bottles,’ he said.

‘I’ll throw out the candles,’ she said. ‘But before that, what kind of year has it been?’

‘Really great,’ he said. ‘I’ve never known a greater pal, a greater buddy, a greater companion.’

‘Same goes here,’ she said. ‘Where did we meet?’

‘You know. It was the library. I saw you prowling the stacks almost every day I was there, for about a week. You seemed to be looking for something. Maybe it wasn’t a book.’

‘Well then,’ she said. ‘Maybe it wasyouafter all. I saw you wandering the stacks, saw you studying the books. The first thing you said to me was, “How about Jane Austen?” What a peculiar thing for a man to say. Most men don’t read Jane Austen, or if they did they wouldn’t admit it or open a conversation with a line like that.’

‘That wasn’t a line,’ he said. ‘I thought you looked like a reader of Jane Austen, or maybe even Edith Wharton. It was quite natural.’

‘From there,’ she said, ‘it really opened out. I remember we began to walk through the stacks together and you pulled out a special edition of Edgar Allan Poe to show me, and though I never was a Poe fan, the way you talked about him, the way you inspired me, I began to read the awful man the next day.’

‘So,’ he said, ‘it was Austen and Wharton and Poe. Those are great names for a literary company.’

‘And then you asked me if I played tennis and I said yes. You said you were better at badminton but you’d try tennis with me. So we played against each other and that was great…I think one of the mistakes we made was that this week, for the first time ever, we played doubles and we played together against the other two.’

‘Yes, that was a great mistake. As long as I opposed you, there was no chance for any candles or any champagne. Maybe that’s not strictly true, but you beating me all the time, I must admit, made it difficult.’

She laughed quietly. ‘Well then, I have to admit that when we became a team on the court and won the game yesterday, not long after that, without thinking, I went out and bought the candles.’

‘Good God,’ he said.

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘Isn’t life strange?’ She paused and looked at the ceiling again. ‘Are we almost there?’

‘Where?’

‘Back where we should be. Back a year ago, a month ago, hell, even a week ago. I’d settle even for that.’

‘Keep talking,’ he said.

‘No, you,’ she said. ‘You’ve got to help.’

‘Well then, it was those days driving up the coast and back. We never stayed overnight. We just loved the drive in the open car with the wind and the sea and there was one hell of a lot of laughter.’

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘That’s it, isn’t it? When you think back about all your friends and all the most important times in your life, laughter is the greatest gift. We did much of that.’

‘You actually went to some of my lectures and didn’t fall asleep.’

‘How could I? You’ve always been brilliant.’

‘No,’ he said. ‘A genius, yes, but not brilliant.’

She laughed again, quietly.

‘You’ve been reading too much Bernard Shaw lately.’

‘Does it show?’

‘Yes, but I don’t mind. Genius or brilliant, the talk has been fine.’

‘How are we doing?’ he said.

‘I think we’re getting close,’ she said. ‘I’m almost back to six months ago. If we keep going, it will be a year. And tonight will be just some sort of bright, wonderful, dumb memory.’

‘Well put,’ he said. ‘Keep talking.’

‘Another thing,’ she said. ‘In all our travels, from breakfast at the seaside to lunch in the mountains to dinner in Palm Springs, we were always home before midnight–me dropped off at the door and you driving off.’

‘That’s right. What wonderful trips. Well now,’ he said, ‘how do you feel?’

‘I think I’m there,’ she said. ‘This un-pillow talk was a great idea.’

‘Are you back in the library and walking, all by yourself?’

‘Yes.’

‘I’ll follow after a while,’ he said. ‘Just one more thing.’

‘Yes?’

‘At noon tomorrow, tennis, but this time you’re across the net again and we play against each other, like in the old days, and I’ll win and you’ll lose.’

‘Don’t be so sure. Noon. Tennis. Just like the old times. Anything else?’

‘Don’t forget to buy the beer.’

‘Beer,’ she said. ‘Yes. Now what? Friends?’

‘What?’

‘Friends?’

‘Of course.’

‘Good. Now, I’m very tired; I need sleep, but I’m feeling better.’

‘Me, too,’ he said.

‘So, my head’s on the pillow, your head’s on yours, but before we go to sleep there’s one more thing.’

‘What?’

‘Can I hold your hand? Just that.’

‘Of course.’

‘Because I have a terrible feeling,’ she said, ‘that the bed might spin and you’ll be thrown off and I’ll wake up to find you’re not holding my hand.’

‘Hold on,’ he said.

His hand touched hers. They lay very straight, very still.

‘Good night,’ he said.

‘Oh, yes, good, good night,’ she said.

The End