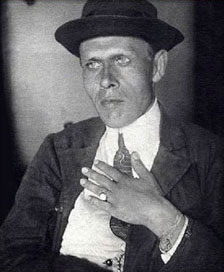

Daniil Ivanovich Kharms (real name Yuvachev; December 17 (30), 1905, St. Petersburg – February 2, 1942, Leningrad) – Russian and Soviet writer, poet and playwright. Founder of the OBERIU association.

He was repressed and arrested on August 23, 1941. He died in a prison hospital on February 2, 1942 in Leningrad. Rehabilitated on July 25, 1960.

Daniil Yuvachev was born on December 17 (30), 1905 in St. Petersburg in the family of Ivan Pavlovich Yuvachev (1860-1940) and Nadezhda Ivanovna Yuvacheva (Kolubakina) (1869-1929). Daniil Ivanovich himself considered January 1 as his birthday. Later, he loved to tell pseudo-autobiographical, absurdist stories about his birth, leaving several texts on this topic (“Now I will tell …”, “The Incubator Period” – both 1935). I.P. Yuvachev was a People’s Volya revolutionary who was exiled to Sakhalin and became a spiritual writer. Daniel’s father was familiar with A.P. Chekhov, L.N. Tolstoy, M.A. Voloshin and N.A. Morozov.

In 1915-1918 (according to other sources, in 1917-1918) Daniil Yuvachev studied at a secondary school (Realschule), which was part of the Main German School of St. Peter (Petrishule), in 1922-1924 – at the 2nd Children’s Village Unified Labor school, from 1924 – at the First Leningrad Electrical Technical School, from where he was expelled in February 1926. On September 15, 1926, he was enrolled as a student in film courses at the State Institute of Art History.

Beginning of literary activity

Around 1921-1922, Daniil Yuvachev chose the pseudonym “Kharms”. Researchers have put forward several versions of its origin, finding sources in English, German, French, Hebrew, and Sanskrit. In the writer’s manuscripts there are about forty pseudonyms (Kharms, Haarms, Dandan, Charms, Karl Ivanovich Shusterling and others). When submitting an application to join the All-Russian Union of Poets on October 9, 1925, Kharms answered the questionnaire questions as follows:

Last name, first name, patronymic: Daniil Ivanovich Yuvachev-Kharms

Literary pseudonym: No, I write Kharms

In 1924-1926, Kharms began to participate in the literary life of Leningrad: he performed reading his own and others’ poems in various halls, and joined the “DSO Order of Brainiacs,” organized by Alexander Tufanov. In March 1926, he became a member of the Leningrad branch of the All-Russian Union of Poets (expelled for non-payment of membership fees in March 1929). This period is characterized by Kharms’s turn to “abstract” creativity, which occurred under the influence of the works of Velimir Khlebnikov, Alexei Kruchenykh, Alexander Tufanov, Kazimir Malevich.

In 1925, Kharms met members of the poetic and philosophical circle “plane trees,” which included Alexander Vvedensky, Leonid Lipavsky, Yakov Druskin and others. Since 1926, Kharms has been actively trying to unite the forces of the “left” writers and artists of Leningrad. In 1926-1927, he organized several literary associations (“Left Flank”, “Academy of Left Classics”). In the fall of 1927, a group of writers led by Kharms received their final name – OBERIU (“Union of Real Art”). OBERIU included Daniil Kharms, Alexander Vvedensky, Nikolai Zabolotsky, Konstantin Vaginov, Igor Bakhterev, Boris (Doivber) Levin, Klimenty Mints and others. The brightest page in the existence of OBERIU was the “Three Left Hours” evening, which took place on January 24, 1928. At this theatrical performance, the Oberiuts read their works, and Kharms’ play “Elizabeth Bam” was staged.

Children’s literature

At the end of 1927, Samuil Marshak, Nikolai Oleinikov and Boris Zhitkov attracted members of OBERIU to work in children’s literature. From the late 1920s to the late 1930s, Kharms actively collaborated with children’s magazines “Hedgehog”, “Chizh”, “Cricket”, “Oktyabryata”, where his poems, stories, captions for drawings, comic advertisements and puzzles were published. Unlike, for example, Alexander Vvedensky, Kharms took a very responsible approach to working in children’s literature, which was for him a constant and almost the only source of income. As N.I. Khardzhiev, a researcher of the Russian avant-garde and friend of the Oberiuts, noted,

Vvedensky was a hack in children’s literature: he wrote terrible books, there were very few good ones… And Kharms, it seems, wrote only six children’s books and very good ones – he did not like it, but he could not write badly.

In the period from 1928 to 1931, 9 illustrated books of poems and stories for children were published – “The Naughty Traffic Jam” (banned by censorship in the period from 1951 to 1961), “About how Kolka Pankin flew to Brazil, and Petka Ershov did not believe anything “”, “Theatre”, “First and Secondly”, “Ivan Ivanovich Samovar”, “About how the old lady bought ink” (classified as one of the books “not recommended for public libraries”), “Game”, “About how my dad shot my ferret,” “Million.” In 1937, Wilhelm Busch’s book “Plikh and Plyukh” was published, translated by Kharms. In 1940, Kharms’ book “The Fox and the Hare” was published, and in 1944, the poem “The Amazing Cat” was published in a separate publication, but anonymously. Also during the writer’s lifetime, separate editions of the poem “Jolly Siskins,” written together with S. Marshak, and the book “Stories in Pictures,” the text of which was written by Kharms, Nina Gernet and Natalya Dilaktorskaya, were published.

First arrest

In December 1931, Kharms, Vvedensky, and Bakhterev were arrested on charges of participating in an anti-Soviet group of writers, and the reason for the arrest was their work in children’s literature, and not the noisy shocking speeches of the Oberiuts. Kharms was sentenced by the OGPU board to three years in correctional camps on March 21, 1932 (the term “concentration camp” was used in the text of the sentence) [K 1]. As a result, on May 23, 1932, the sentence was replaced by deportation (“minus 12”), and the poet went to Kursk, where the exiled Alexander Vvedensky was already located.

Kharms arrived in Kursk on July 13, 1932 and settled in house number 16 on Pervyshevskaya Street (now Ufimtseva Street). Kharms returned to Leningrad on October 12, 1932.

1930s

After returning from exile, a new period begins in Kharms’ life: OBERIU’s public appearances stop, the number of children’s books published by the writer decreases, and his financial situation becomes very difficult. In Kharms’s work there is a transition from poetry to prose. J.-F. Jacquard identified two major periods in the writer’s work, separated by a deep ideological crisis of 1932-1933: the first period (1925 – early 1930s) – metaphysical and poetic, associated with the utopian project of creating the world with the help of the poetic word, the second (1933-1941 years) – prosaic, expressing the failure of the metaphysical project, the collapse of the image of the world and the literary language itself.

Realizing that he will not be able to publish anything other than works for children, Kharms nevertheless does not stop writing. In the 1930s, he created his main works – the cycle of stories “Cases”, the story “The Old Woman”, as well as a huge number of short stories, poems, sketches in prose and verse.

In the summer of 1934, Kharms married Marina Malich. He continues to communicate with Alexander Vvedensky, Leonid Lipavsky, Yakov Druskin, with whom he forms a friendly circle of “plane trees”. They met several times a month to discuss recently written works and various philosophical issues. You can get an idea of these meetings from “Conversations” by Leonid Lipavsky, which are a recording of conversations between D. Kharms, A. Vvedensky, N. Oleinikov, Y. Druskin, T. Meyer, L. Lipavsky in the mid-1930s. In the late 1930s, Kharms was also friendly with the young art critic and aspiring writer Vsevolod Petrov, who in his memoirs calls himself “Kharms’s last friend.”

Second arrest and death

On August 23, 1941, Kharms was arrested for spreading “slanderous and defeatist sentiments” among his circle. The arrest warrant cites the words of Kharms, which, as A. Kobrinsky writes, were copied from the text of the denunciation:

The Soviet Union lost the war on the first day, Leningrad will now either be besieged or starve to death, or be bombed, leaving no stone unturned… If they give me a mobilization leaflet, I’ll punch the commander in the face, let them shoot me; but I won’t wear a uniform and I won’t serve in the Soviet troops, I don’t want to be such shit. If I am forced to shoot from a machine gun from attics during street battles with the Germans, then I will not shoot at the Germans, but at them from the same machine gun.

On August 21, 1941, on the basis of this denunciation, the NKVD detective sergeant of state security Burmistrov wrote an indictment. It determined the fate of the poet. At the same time, apart from the denunciation and indictment of Burmistrov, there is no evidence of the so-called. Kharms’ “pro-German” sentiments. In 1941, in double issue No. 8-9 of the children’s magazine “Murzilka” (subscribed for publication on September 5, 1941), D. Kharms’s last lifetime children’s poem (“In the yard in a green cage…”) was published.

Literary critic Gleb Morev and poet and translator Valery Shubinsky write: “Back in the spring of 1941, Nina Gernet Kharms said: “There will be a war. Leningrad faces the fate of Coventry.” According to L. Panteleev, Kharms was “patriotic” – “he believed that the Germans would be defeated, that it was Leningrad – the resilience of its inhabitants and defenders – that would decide the fate of the war.” True, Panteleev’s “Leningrad Records” were published in 1965 – their text was undoubtedly auto-censored. Kharms also told Yakov Druskin that the USSR would win the war, but with a different connotation: “The Germans will get stuck in this swamp.” None of Kharms’ acquaintances (including his wife) says anything about his “pro-German” sentiments. There is no evidence that he pinned his hopes of getting rid of Soviet power—or any hopes at all—to the war.”

Kharms’ premonitions are also evidenced by his words quoted in the siege diary of the artist and poet Pavel Zaltsman:

On one of the first days, I accidentally met Kharms at Glebova’s. He was wearing breeches and carrying a thick stick. He and his wife were sitting together; his wife was young and pretty. There were no worries yet, but, knowing well about the fate of Amsterdam, we imagined everything that would be possible. He said that he expected and knew about the day the war began and that he agreed with his wife that, according to his well-known telegraphic word, she should leave for Moscow. Something changed their plans, and he, not wanting to part with her, came to Leningrad. As he left, he set his expectations: this was what haunted everyone: “We will crawl away without legs, holding on to the burning walls.” One of us, maybe his wife, or maybe I, laughingly, noticed that it was enough to lose your legs for it to be difficult to crawl, even clutching entire walls. Or burn with uncut legs. As we shook hands, he said, “Maybe, God willing, we’ll see each other.” I listened carefully to all these confirmations of general thoughts and mine too.

To avoid execution, the writer feigned madness; The military tribunal determined, “based on the gravity of the crime committed,” to keep Kharms in a psychiatric hospital. Daniil Kharms died on February 2, 1942 during the siege of Leningrad, in the most difficult month in terms of the number of starvation deaths, in the psychiatry department of the Kresty prison hospital (St. Petersburg, Arsenalnaya street, building 9).

Kharms’ wife Marina Malich was initially falsely informed that he had been taken to Novosibirsk.

On July 25, 1960, at the request of Kharms’ sister Elizaveta Gritsina, the Prosecutor General’s Office found him not guilty. His case was closed for lack of evidence of a crime, and he himself was rehabilitated.

The most likely burial place is Piskarevskoye Cemetery (grave No. 9 or No. 23).

Family and personal life

On March 5, 1928, Kharms married Esther Aleksandrovna Rusakova (née Ioselevich; 1909-1943), who was born in Marseille in the family of an emigrant from Taganrog, A.I. Ioselevich. Many of the writer’s works, written from 1925 to 1932, are dedicated to her, as well as numerous diary entries that testify to their difficult relationship. In 1932 they divorced.

Esther Rusakova was arrested along with her family in 1936 on charges of Trotskyist sympathies and sentenced to 5 years in the camps in Kolyma, where she died in 1938 (according to official information, she died in 1943). Her brother, convicted at the same time as her, is the composer Paul Marcel (Pavel Rusakov-Ioselevich; 1908-1973), the author of the pop hit “Friendship” (When with a simple and tender gaze…, 1934) to the words of Andrei Shmulyan, who was part of the repertoire of Vadim Kozin and Klavdia Shulzhenko. Her sister Bluma Ioselevich (Lyubov Rusakova) became the wife of revolutionary Viktor Kibalchich.

On July 16, 1934, Kharms married Marina Vladimirovna Malich (1912-2002), with whom he lived until his arrest in 1941. The writer also dedicated a number of works to his second wife. After the death of Kharms, Marina Malich was evacuated from Leningrad to the Caucasus, where she came under German occupation and was taken to Germany as an ostarbeiter; after the end of World War II she lived in Germany, France, Venezuela, and the USA. In the mid-1990s, literary critic V. Glotser found M. Malich and wrote down her memories, which were published in the form of a book.

Editions of works

Archive of Daniil Kharms

Unlike the archives of Oleinikov and Vvedensky, which were only partially preserved, the Kharms archive was preserved. The archive was saved thanks to the efforts of Yakov Druskin, who in 1942, together with Marina Malich, collected the manuscripts in a suitcase and took them out of the writer’s house that was damaged by the bombing. V. Glotser described the writer’s archive as follows:

Since 1928, D. Kharms … does not even retype his manuscripts on a typewriter – as it is unnecessary. And from then on, all his manuscripts… are in the full sense of the word manuscripts, autographs. Kharms wrote either on separate sheets and pieces of paper (smooth, or torn from a ledger or from a notebook, or notebooks, or on the back of cemetery forms, invoices of a “laundry establishment”, tables of fasteners and point screws, the back of printed notes, pages from an employee’s notebook magazine “Hygiene and Health of the Working and Peasant Family”, etc.), or in notebooks (school or general), in ledgers, in notebooks, and very rarely – in various kinds of homemade books (“Blue Notebook”, etc.).

Yakov Druskin transferred the main part of the archive to the Manuscript Department of the State Public Library. M.E. Saltykov-Shchedrin (now the Russian National Library, F. 1232), the other part entered the Manuscript Department of the Institute of Russian Literature (Pushkin House).

Lifetime editions

During Kharms’s lifetime, only two of his “adult” poems were published. The first publication took place in 1926, after Kharms joined the Union of Poets: the poem “Chinar-Gazeer (an incident on the railway)” was published in the Union’s almanac. In 1927, “The Verse of Peter Yashkin the Communist” was published in the anthology “Koster”. The word “Communist” from the title was removed by censorship. A number of projects to publish collections of works by Oberiuts were not implemented.

Works for children were published in children’s magazines and published in separate editions.

Publications from the 1960s to the 2000s

In 1965, two poems by Kharms were published in the Leningrad edition of the collection “Poetry Day,” which marked the beginning of the publication of “adult” works by Kharms in the USSR and abroad. Since the late 1960s, some “adult” works by Kharms have been published in USSR periodicals, which are presented as humorous. For example, in the collection “Club of 12 Chairs” (works published on the humorous page of the same name in the Literary Gazette) Kharms’ stories “Fairy Tale”, “Bale” and “Anecdotes from the Life of Pushkin” were published. The publication is preceded by a foreword by Viktor Shklovsky “On Colorful Dreams. A word about Daniil Kharms.”

During this period, a much larger number of texts by Kharms and other Oberiuts began to be circulated in samizdat. Individual editions of the writer’s works first appeared abroad in the 1970s. In 1974, the American Slavist George Gibian prepared for publication the book “Daniil Kharms. Favorites”, which contained stories, poems, the story “The Old Woman”, the play “Elizabeth Bam”, as well as works for children. Another publication was undertaken by Mikhail Meilakh and Vladimir Erl, releasing four volumes of the “Collected Works” out of nine planned in 1978-1988 in Bremen.

In the children’s magazine “Murzilka” in No. 4 for 1966, the poem “Cats” by D. Kharms was published, in No. 1 for 1976 – the poem “Ship. Amazing cat.”

The first Soviet edition of the “adult” works “Flight to Heaven” was published only in 1988 by the publishing house “Soviet Writer”. The most complete (however, criticized for errors in deciphering manuscripts) publication at the moment is the 6-volume “Complete Works,” published in the second half of the 1990s by Valery Sazhin in the Academic Project publishing house.

Currently, the repertoire of a number of publishing houses constantly includes collections and collected works of Kharms, which are republished from year to year.

Impact on culture

The processes of understanding Kharms’s work and his influence on domestic literature, both unofficial Soviet literature and subsequent Russian literature, begin only in the last third of the 20th century. After former members of the Leningrad literary group “Helenukty” gained access to the legacy of Kharms and other Oberiuts in the early 1970s, the poetics of OBERIU in one way or another influenced the work of Alexei Khvostenko, Vladimir Erl, as well as Henri Volokhonsky, who was not part of the group .

Despite the fact that Kharms was practically not considered from the perspective of postmodern reading, researchers trace Kharms’ influence on Russian rock (Boris Grebenshchikov, Anatoly Gunitsky, Vyacheslav Butusov, NOM, “Umka and Bronevik”), on modern Russian fairy tale (Yuri Koval), Russian literary postmodern (Viktor Pelevin), film dramaturgy (“Epitaph of a plaster pioneer in the manner of Daniil Kharms”), they have yet to study the influence that Kharms’s work has had on modern literature and art.

On December 22, 2005, in St. Petersburg, at house 11 on Mayakovsky Street, in which Kharms lived, a memorial plaque by the architect V. Bukhaev was unveiled on the occasion of the writer’s centenary. Artist D. V. Shagin, author of the project People’s Artist of the Russian Federation V. E. Receptor. The composition consists of a marble relief portrait, a flower shelf and a prison still life; a line from Kharms’ poem “A Man Came Out of the House” is engraved on the board; the inscription reads: “The writer Daniil Kharms lived here from 1925 to 1941.”

The asteroid (6766) Kharms, discovered by astronomer Lyudmila Karachkina at the Crimean Astrophysical Observatory on October 20, 1982, a street in the Krasnogvardeisky district of St. Petersburg, is named after Daniil Kharms.

As part of the festival dedicated to the 100th anniversary of Kharms, two monuments were erected. “The village of Veretyevo has a chance to become a kind of Mecca for admirers of the talent of Daniil Kharms. One of the structures is a metal pillar with Kharms’ “head” at the top. The composition is complemented by a “stream” of old women falling from above – characters from one of the writer’s works. The author of the work was the sculptor Pavlov. The idea of another monument belongs to the Kyiv artist Stolbchenko. A stylized bench and a three-legged table were installed against the backdrop of the sun with its rays. And the table supports are figurines of Kharms’s characters, turned upside down.”

In 2006, a graffiti-style portrait of Kharms, 2 floors high, appeared on the wall of house 11 on the street. Mayakovskaya in St. Petersburg. In October 2021, the Dzerzhinsky District Court decided to paint over the portrait. On June 3, 2022, the graffiti was painted over by utility services; according to the services, the portrait will be replaced by a light projection.

Interesting Facts

Kharms is mistakenly credited with the authorship of a series of literary anecdotes “Jolly Fellows” (“Once Gogol dressed up as Pushkin…”), created in the 1970s by the editorial office of the magazine “Pioneer” in imitation of Kharms (he actually owns a number of parody miniatures about Pushkin and Gogol). The appearance of literary jokes by pseudo-Kharms coincided with the 150th anniversary of the birth of F. M. Dostoevsky, whose name appears in 16 jokes, and the book was published in 1998.

The first dissertation in the USSR about the Oberiuts and Kharms (“The Problem of the Funny in the Works of the Oberiuts”) was written by Anna Gerasimova (Umka), who sometimes gives public readings of his stories

Address in St. Petersburg

St. Mayakovskogo, 11, apt. No. 8 (1926—1941)

List of works by Daniil Kharms

Films with Kharms

1929 – Mail, director Mikhail Tsekhanovsky – cartoon based on a poem by S. Marshak, sound version. D. Kharms – author of the text, entertainer

Film adaptations of works by Daniil Kharms

1972 – “Merry Carousel” issue No. 4 “The Merry Old Man” is a Soviet short hand-drawn cartoon created by director Anatoly Petrov. The third of three stories in the animated anthology.

1984 – “Plikh and Plikh”, a puppet cartoon based on the book by Wilhelm Busch “Plikh and Plikh”, translated by Kharms, directed by Nathan Lerner

1985 – “Change No. 4”, cartoon collection: plot “Liar”, director Alexey Turkus

1987 – “The Kharms Case”, a surreal film parable, directed by Slobodan Pesic

1987 – “Samovar Ivan Ivanovich”, cartoon based on Kharms’ poems for children

1989 – “Clowning”, a tragicomedy of the absurd based on the works of Kharms, directed by Dmitry Frolov

1989 – “Journey”, cartoon based on the story for children “Firstly and Secondly”

1990 – “The Case”, a cartoon based on three miniatures by D. Kharms on the themes of city life in the 1930s, directed by Alexey Turkus

1990 – “Bale!”, cartoon by the creative association “Ekran” based on the stories of M. Zoshchenko and D. Kharms

1990 – “Merry Carousel” issue No. 21 “Once upon a time” – the second of two stories in the animated almanac.

1991 – “Staru-kha-rmsa”, film adaptation of the story “The Old Woman”, director Vadim Gems

1991 – “Fairy Tale”, film adaptation of the work of the same name, Soyuzmultfilm studio

1995 – “Concert for a Rat”, a film in the genre of political absurdity based on the works of Kharms, directed by Oleg Kovalov

1996 – “Charms Zwischenfälle” (Harms Cases), a film by Austrian director Michael Kreisl based on the story “The Old Woman”, stories and biography of Charms.

1999 – “Falling”, an amateur film in the genre of an absurdist detective story based on the story “The Old Woman”, director Nikolai Kovalev, leader of the group Safe

1999 – “Pád” (The Fall), a short Czech-Canadian cartoon that received several international awards, directed by Aurel Klimt

2002 — “Dangerous Walk” (cartoon)

2007 – “The Janitor on the Moon”, (cartoon) based on Kharms’ poem “The Constancy of Fun and Dirt”

2009 – “A Play for a Man”, one-man show based on the works of Kharms, director Vladimir Mirzoev

2010 — “Harmonium”, cartoon based on the works of Kharms

2010 – “Interference”, a short film based on the story of the same name, directed by Maxim Buinitsky

2011 – “Malgil”, (1, 2), short film by Yaroslav Ivanov and Dmitry Fetisov based on the works of Kharms

2013 — “Out the window. Stories from the life of Kharms” (cartoon).

Films about Kharms

1989 – “But they didn’t understand the words he said” – documentary film (directed by Tatyana Chivikova), Tsentrnauchfilm

1989 – “The Kharms Passion”, documentary television film (directed by L. Kostrichkin)

2006 — “Three left clocks. Kharms. Another Line”, documentary film (directed by Varvara Urizchenko)

2007 – “Falling into Heaven”, full-length feature film (director Natalya Mitroshina)

2008 – “Manuscripts don’t burn… Film 2. “The Case of Daniil Kharms and Alexander Vvedensky”, documentary film (directed by Sergei Golovetsky)

2013 — “Out the window. Stories from the life of Kharms”, animated (directed by Mikhail Safronov)

2015 – “Cucumber, or the Meanness of the Russian Cucumber” / fr. Ogurets, ou les turpitudes d’un concombre russe, short feature film (director Eric Bu)

2017 — “Kharms” full-length feature film (director Ivan Bolotnikov)

Music

“1000 Pioneers” – poems by Daniil Kharms and music by Boris Savelyev (1985) (Popov Big Children’s Choir). The premiere took place on May 19, 1985 in Moscow on Red Square.

“The Legend of Tobacco” is a song by Alexander Galich, dedicated to Daniil Kharms, 1969.

“Three Choirs to the Poems of Daniil Kharms” – a cycle by Viktor Suslin for a female choir and a girl reader (“Tiger on the Street”, “Cats”, “Patter”), 1972.

“The Blue Notebook” is a work by Edison Denisov for soprano, reader, violin, cello, two pianos and three groups of bells, based on poems by Alexander Vvedensky and texts by Daniil Kharms (in 10 parts, 1984). The premiere took place on April 11, 1985 in Rostov-on-Don, the soloist was Elena Komarova.

“Love and Life of a Poet” – vocal cycle by Leonid Desyatnikov based on poems by Daniil Kharms and Nikolai Oleinikov, 1989.

“Kharms-10 – cases” – album of the free jazz ensemble “Moscow Composers Orchestra” (all lyrics belong to Kharms), 1998.

“Charms” is an album by Belgian composer and musician Peter Vermeersch with lyrics by Charms and music written for the theater production of the same name, performed by the group Walpurgis in collaboration with the Vooruit Arts Center, 1998.

Album “Messengers”, musical project “Snake Paradise” – numbers based on prose texts by Kharms, shown as part of the celebration of the writer’s centenary in Belgrade, 2005.

“Kharms FM” is a collection of Kharms’ works in the musical interpretation of the “Other Creative” community with the participation of Vyacheslav Butusov, 2008.

“Guidon” is a choral opera by Alexander Manotskov based on the play “Guidon” and other poems by Daniil Kharms, 2009.

“How Volodya quickly flew downhill” is a work by Irina Alekseychuk for a mixed choir a’cappella based on poems by Daniil Kharms.

“Kharms is Alive” is a vocal cycle based on the texts of literary jokes by Daniil Kharms, performed by the Krylov Quartet (creative association “Pakava It”).

“The Janitor” is a song by the folk group Otava Yo based on poems by Daniil Kharms, 2012.

“Pseudo Matrix named after the Cruel Romantic”, “Name Day of Daniil Ivanovich Kharms” – two songs from the Cyber Ra album “Name Day of Kharms”, 2013.

“The Constancy of Fun and Dirt” is a joint album by Leonid Fedorov and the group “Kruzenshtern and Steamboat” with lyrics by Daniil Kharms, 2018.

“To Unknown Natasha” – album by the group “Waltz in the Congo” based on poems by Daniil Kharms, 2013.

“Kharms” is an album based on poems by Kharms from the group “Buli for Granny” with the participation of Alexander Liver, 2022.

“With a baton and a bag” – song by the group “Kushva Band” (Samara, music author – Evgeny Zhevlakov), 2018.

Theater productions

Drama Theater

“Synphony No. 2” is a performance by the Lusores Theater, directed by Alexander Savchuk.

“Harms! Charms! Shardam! — Hermitage Theater, Moscow. Premiere: 04/21/1982

“Elizabeth Bam” is a play directed by Fyodor Sukhov based on the play of the same name by Daniil Kharms. The premiere took place at the Embankment Theater on March 22, 1989 (renewal on March 22, 2009).

“White Sheep” is “a performance-spell dedicated to Oleg Nikolaevich Efremov.” Moscow Hermitage Theater (2000).

“The Old Woman” is a collaboration (production, set design, lighting concept) between director Robert Wilson and actors Willem Dafoe and Mikhail Baryshnikov. The premiere took place on July 4, 2013 at the Manchester International Festival.

“Three Left Clocks” (absurd comedy) – a performance by the Primorsky Regional Youth Theater (Vladivostok) based on the works of Daniil Kharms, directed by Lydia Vasilenko. The premiere took place on April 4, 2014.

“Kharms” is a performance based on the works of Daniil Kharms, directed by Sergei Filatov. The premiere took place at the St. Petersburg Academic Theater named after Lensoveta on February 6, 2015.

“Harms. Myr” – “Gogol Center”, director Maxim Didenko.

“11 Statements of Daniil Ivanovich Kharms” – staged by Vladimir Krasovsky of the Pereulok theater group at the MGIKA educational theater in 2009. The performance took part in the “YOUR CHANCE” festival and the “Left Bank” festival.

“Breathing (answer to Aristotle)” is an interactive solo performance. Saint Petersburg. “Three letter theater” Directors: Sergei Gogun and Kirill Chumakov.

“Second Breath (dialogue with Solomon)” – Interactive solo performance. Saint Petersburg. “Three letter theater” Directors: Sergei Gogun and Kirill Chumakov.

“Unsuccessful Performance” – theater studio “On the Third Floor”. Directed by Larisa Karaseva. 2015. 1st degree laureate at the All-Russian festival “Rainbow of Childhood”. The performance is dedicated to Ekaterina Okhotnikova.

“Daniil Kharms. History of SDYGR APPR” – a one-man show by Alexander Lushin based on the works and diary entries of Kharms. Director Yuri Vasiliev. “Takoy Theater” (St. Petersburg)

“Four-legged Crow” – Moscow Youth Theater. Directed by Pavel Artemyev.

“Kharms, Kharms and AGAIN Kharms” – production by Yuri Tomoshevsky (director Sergei Safronov). Saint Petersburg. Premiere May 11, 2017.

Ballet

“Old Women Falling Out” is a ballet by Alexei Ratmansky to the music of the vocal cycle by Leonid Desyatnikov. The premiere took place on October 6, 2007 as part of the Territory Festival.

Opera

“Guidon” is an opera by Alexander Manotskov, staged by the School of Dramatic Art theater. The premiere took place in November 2009, and in 2011 the performance received the Golden Mask award (in the Experiment category).