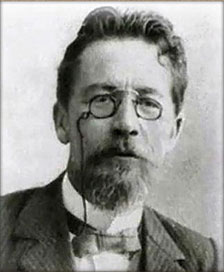

At Home, Chekhov Anton

“They sent over from Grigorievitch’s for some book, but I said that you were not at home. The postman has brought the newspapers and two letters. And, Evgeniy Petrovich, I really must ask you to do something in regard to Serozha. I caught him smoking the day before yesterday, and again to-day. When I began to scold him, in his usual way he put his hands over his ears, and shouted so us to drown my voice.”

Evgeniy Petrovich Buikovsky, Procurer of the District Court, who had only just returned from the Session House and was taking off his gloves in his study, looked for a moment at the complaining governess and laughed:

“Serozha smoking!” He shrugged his shoulders. “I can imagine that whipper-snapper with a cigarette! How old is he?”

“Seven. Of course you may not take it seriously, but at his age smoking is a bad and injurious habit, and bad habits should be rooted out in their beginning.”

“Very true. But where does he get the tobacco?”

“On your table.”

“On my table! Ask him to come here.”

When the governess left the room, Buikovsky sat in his armchair in front of his desk, shut his eyes, and began to think. He pictured in imagination his Serozha with a gigantic cigarette a yard long, surrounded by clouds of tobacco smoke. The caricature made him laugh in spite of himself; but at the same time the serious, worried face of his governess reminded him of a time, now long passed by, a half-forgotten time, when smoking in the schoolroom or nursery inspired in teachers and parents a strange and not quite comprehensible horror. No other word but horror would describe it. The culprits were mercilessly flogged, expelled from school, their lives marred, and this, although not one of the schoolmasters or parents could say what precisely constitutes the danger and guilt of smoking. Even very intelligent men did not hesitate to fight a vice which they did not understand. Evgeniy Petrovich remembered the director of his own school, a benevolent and highly educated old man, who was struck with such terror when he caught a boy with a cigarette that he became pale, immediately convoked an extraordinary council of masters, and condemned the offender to expulsion. Such indeed appears to be the law of life; the more intangible the evil the more fiercely and mercilessly is it combated.

The Procurer remembered two or three cases of expulsion, and recalling the subsequent lives of the victims, he could not but conclude that such punishment was often a much greater evil than the vice itself…. But the animal organism is gifted with capacity to adapt itself rapidly, to accustom itself to changes, to different atmospheres, otherwise every man would feel that his rational actions were based upon an irrational foundation, and that there was little reasoned truth and conviction even in such responsibilities—responsibilities terrible in their results—as those of the schoolmaster, and lawyer, the writer….

And such thoughts, light and inconsequential, which enter only a tired and resting brain, wandered about in Evgeniy Petrovich’s head; they spring no one knows where or why, vanish soon, and, it would seem, wander only on the outskirts of the brain without penetrating far. For men who are obliged for whole hours, even for whole days, to think official thoughts all in the same direction, such free, domestic speculations are an agreeable comfort.

It was nine o’clock. Overhead from the second story came the footfalls of someone walking from corner to corner; and still higher, on the third story, someone was playing scales. The footsteps of the man who, judging by his walk, was thinking tensely or suffering from toothache, and the monotonous scales in the evening stillness, combined to create a drowsy atmosphere favourable to idle thoughts. From the nursery came the voices of Serozha and his governess.

“Papa has come?” cried the boy, “Papa has co-o-me! Papa! papa!”

“Votre père vous appelle, allez vite,” cried the governess, piping like a frightened bird…. “Do you hear?”

“What shall I say to him?” thought Evgeniy Petrovich.

And before he had decided what to say, in came his son Serozha, a boy of seven years old. He was one of those little boys whose sex can be distinguished only by their clothes—weakly, pale-faced, delicate…. Everything about him seemed tender and soft; his movements, his curly hair, his looks, his velvet jacket.

“Good evening, papa,” he began in a soft voice, climbing on his father’s knee, and kissing his neck. “You wanted me?”

“Wait a minute, wait a minute, Sergey Evgenich,” answered the Procuror, pushing him off. “Before I allow you to kiss me I want to talk to you, and to talk seriously…. I am very angry with you, and do not love you any more … understand that, brother; I do not love you, and you are not my son…. No!”

Serozha looked earnestly at his father, turned his eyes on to the chair, and shrugged his shoulders.

“What have I done?” he asked in doubt, twitching his eyes. “I have not been in your study all day and touched nothing.”

“Natalya Semyonovna has just been complaining to me that she caught you smoking…. Is it true? Do you smoke?”

“Yes, I smoked once, father…. It is true.”

“There, you see, you tell lies also,” said the Procurer, frowning, and trying at the same time to smother a smile. “Natalya Semyonovna saw you smoking twice. That is to say, you are found out in three acts of misconduct—you smoke, you take another person’s tobacco, and you lie. Three faults!”

“Akh, yes,” remembered Serozha, with smiling eyes. “It is true. I smoked twice—to-day and once before.”

“That is to say you smoked not once but twice. I am very, very displeased with you! You used to be a good boy, but now I see you are spoiled and have become naughty.”

Evgeniy Petrovich straightened Serozha’s collar, and thought: “What else shall I say to him?”

“It is very bad,” he continued. “I did not expect this from you. In the first place you have no right to go to another person’s table and take tobacco which does not belong to you. A man has a right to enjoy only his own property, and if he takes another’s then he is a wicked man.” (This is not the way to go about it, thought the Procuror.) “For instance, Natalya Semyonovna has a boxful of dresses. That is her box, and we have not, that is neither you nor I have, any right to touch it, as it is not ours…. Isn’t that plain? You have your horses and pictures … I do not take them. Perhaps I have often felt that I wanted to take them … but they are yours, not mine!”

“Please, father, take them if you like,” said Serozha, raising his eyebrows. “Always take anything of mine, father. This yellow dog which is on your table is mine, but I don’t mind….”

“You don’t understand me,” said Buikovsky. “The dog you gave me, it is now mine, and I can do with it what I like; but the tobacco I did not give to you. The tobacco is mine.” (How can I make him understand? thought the Procurer. Not in this way). “If I feel that I want to smoke someone else’s tobacco I first of all ask for permission….”

And idly joining phrase to phrase, and imitating the language of children, Buikovsky began to explain what is meant by property. Serozha looked at his chest, and listened attentively (he loved to talk to his father in the evenings), then set his elbows on the table edge and began to concentrate his short-sighted eyes upon the papers and inkstand. His glance wandered around the table, and paused on a bottle of gum-arabic. “Papa, what is gum made of?” he asked, suddenly lifting the bottle to his eyes.

Buikovsky took the bottle, put it back on the table, and continued:

“In the second place, you smoke…. That is very bad! If I smoke, then … it does not follow that everyone may. I smoke, and know … that it is not clever, and I scold myself, and do not love myself on account of it … (I am a nice teacher, thought the Procurer.) Tobacco seriously injures the health, and people who smoke die sooner than they ought to. It is particularly injurious to little boys like you. You have a weak chest, you have not yet got strong, and in weak people tobacco smoke produces consumption and other complaints. Uncle Ignatius died of consumption. If he had not smoked perhaps he would have been alive to-day.”

Serozha looked thoughtfully at the lamp, touched the shade with his fingers, and sighed. “Uncle Ignatius played splendidly on the fiddle!” he said. “His fiddle is now at Grigorievitch’s.”

Serozha again set his elbows on the table and lost himself in thought. On his pale face was the expression of one who is listening intently or following the course of his own thoughts; sorrow and something like fright showed themselves in his big, staring eyes. Probably he was thinking of death, which had so lately carried away his mother and Uncle Ignatius. Death is a tiling which carries away mothers and uncles and leaves on the earth only children and fiddles. Dead people live in the sky somewhere, near the stars, and thence look down upon the earth. How do they bear the separation?

“What shall I say to him?” asked the Procuror. “He is not listening. Apparently he thinks there is nothing serious either in his faults or in my arguments. How can I explain it to him?”

The Procurer rose and walked up and down the