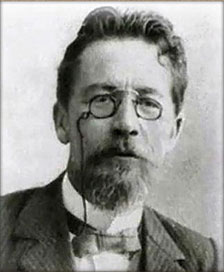

Enemies, Chekhov Anton

At ten o’clock on a dark September evening six-year-old Andrey, the only son of Dr. Kirilov, a Zemstvo physician, died from diphtheria. The doctor’s wife had just thrown herself upon her knees at the bedside of her dead child, and was giving way to the first ecstacy of despair, when the hall-door bell rang loudly. Owing to the danger of infection all the servants had been sent out of the house that morning; and Kirilov, in his shirtsleeves, with unbuttoned waistcoat, with sweating face, and hands burned with carbolic acid, opened the door himself. The hall was dark, and the stranger who entered it was hardly visible. All that Kirilov could distinguish was that he was of middle height, that he wore a white muffler, and had a big, extraordinarily pale face—a face so pale that at first it seemed to illumine the darkness of the hall.

“Is the doctor at home?” he asked quickly.

“I am the doctor,” answered Kirilov, “What do you want?”

“Ah, it is you. I am glad!” said the stranger. He stretched out through the darkness for the doctor’s hand, found it, and pressed it tightly. “I am very … very glad. We are acquaintances. My name is Abogin…. I had the pleasure of meeting you last summer at Gnutcheffs. I am very glad that you are in…. For the love of Christ do not refuse to come with me at once…. My wife is dangerously ill…. I have brought a trap.”

From Abogin’s voice and movements it was plain that he was greatly agitated. Like a man frightened by a fire or by a mad dog, he could not contain his breath. He spoke rapidly in a trembling voice, and something inexpressibly sincere and childishly imploring sounded in his speech. But, like all men frightened and thunderstruck, he spoke in short abrupt phrases, and used many superfluous and inconsequential words.

“I was afraid I should not find you at home,” he continued. “While I was driving here I was in a state of torture…. Dress and come at once, for the love of God … It happened thus. Papchinsky Alexander Semenovich whom you know, had driven over…. We talked for awhile … then we had tea; suddenly my wife screamed, laid her hand upon her heart, and fell against the back of the chair. We put her on the bed…. I bathed her forehead with ammonia, and sprinkled her with water … she lies like a corpse…. It is aneurism…. Come…. Her father died from aneurism….”

Kirilov listened and said nothing. It seemed he had forgotten his own language. But when Abogin repeated what he had said about Papchinsky and about his wife’s father, the doctor shook his head, and said apathetically, drawling every word:

“Excuse me, I cannot go…. Five minutes ago … my child died.”

“Is it possible?” cried Abogin, taking a step hack. “Good God, at what an unlucky time I have come! An amazingly unhappy day … amazing! What a coincidence … as if on purpose.”

Abogin put his hand upon the door-handle, and inclined his head as if in doubt. He was plainly undecided as to what to do; whether to go, or again to ask the doctor to come.

“Listen to me,” he said passionately, seizing Kirilov by the arm; “I thoroughly understand your position. God is my witness that I feel shame in trying to distract your attention at such a moment, but … what can I do? Judge yourself—whom can I apply to? Except you, there is no doctor in the neighbourhood. Come! For the love of God! It is not for myself I ask…. It is not I who am ill.”

A silence followed. Kirilov turned his back to Abogin, for a moment stood still, and went slowly from the anteroom into the hall. Judging by his uncertain, mechanical gait, by the care with which he straightened the shade upon the unlit lamp, and looked into a thick book which lay upon the table—in this moment he had no intentions, no wishes, thought of nothing; and probably had even forgotten that in the anteroom a stranger was waiting. The twilight and silence of the hall apparently intensified his stupor. Walking from the hall into his study, he raised his right leg high, and sought with his hands the doorpost. All his figure showed a strange uncertainty, as if he were in another’s house, or for the first time in life were intoxicated, and were surrendering himself questioningly to the new sensation. Along the wall of the study and across the bookshelves ran a long zone of light. Together with a heavy, close smell of carbolic and ether, this light came from a slightly opened door which led from the study into the bedroom. The doctor threw himself into an armchair before the table. A minute he looked drowsily at the illumined books, and then rose, and went into the bedroom.

In the bedroom reigned the silence of the grave. All, to the smallest trifle, spoke eloquently of a struggle just lived through, of exhaustion, and of final rest. A candle standing on the stool among phials, boxes, and jars, and a large lamp upon the dressing-table lighted the room. On the bed beside the window lay a boy with open eyes and an expression of surprise upon his face. He did not move, but his eyes, it seemed, every second grew darker and darker, and vanished into his skull. With her hands upon his body, and her face hidden in the folds of the bedclothes, knelt the mother. Like the child, she made no movement; life showed itself alone in the bend of her back and in the position of her hands. She pressed against the bed with all her being, with force and eagerness, us if she feared to destroy the tranquil and convenient pose which she had found for her weary body. Counterpane, dressings, jars, pools on the floor, brashes and spoons scattered here and there, the white bottle of lime-water, the very air, heavy and stifling—all were dead and seemed immersed in rest.

The doctor stopped near his wife, thrust his hands into his trouser pockets, and turning his head, bent his gaze upon his son. His face expressed indifference; only by the drops upon his beard could it be seen that he had just been crying.

The repellent terror which we conceive when we speak of death was absent from the room. The general stupefaction, the mother’s pose, the father’s indifferent face, exhaled something attractive and touching; exhaled that subtle, intangible beauty of human sorrow which cannot be analysed or described, and which music alone can express. Beauty breathed even in the grim tranquillity of the mourners. Kirilov and his wife were silent; they did not weep, as if in addition to the weight of their sorrow they were conscious also of the poetry of their position. It seemed that they were thinking how in its time their youth had passed, how now with this child had passed even their right to have children at all. The doctor was forty-four years old, already grey, with the face of an old man; his faded and sickly wife, thirty-five. Andreï was not only their only son, but also their last.

In contrast with his wife, Kirilov belonged to those natures which in time of spiritual pain feel a need for movement. After standing five minutes beside his wife, he, again lifting high his right leg, went from the bedroom into a little room half taken up by a long, broad sofa, and thence into the kitchen. After wandering about the stove and the cook’s bed he bowed his head and went through a little door back to the anteroom. Here again he saw the white muffler and the pale face.

“At last!” sighed Abogin, taking hold of the door-handle. “Come, please!”

The doctor shuddered, looked at him, and remembered.

“Listen to me; have I not already told you I cannot come?” he said, waking up. “How extraordinary!”

“Doctor, I am not made of stone…. I thoroughly understand your position…. I sympathise with you!” said Abogin, with an imploring voice, laying one hand upon his muffler. “But I am not asking this for myself…. My wife is dying! If you had heard her cry, if you had seen her face, then you would understand my persistence! My God! and I thought that you had gone to get ready! Dr. Kirilov, time is precious. Come, I implore you!”

“I cannot go,” said Kirilov with a pause between each word. Then he returned to the hall.

Abogin went after him, and seized him by the arm.

“You are overcome by your sorrow—that I understand. But remember … I am not asking you to come and cure a toothache … not as an adviser … but to save a human life,” he continued, in the voice of a beggar. “A human life should be supreme over every personal sorrow…. I beg of you manliness, an exploit!… In the name of humanity!”

“Humanity is a stick with two ends,” said Kirilov with irritation. “In the name of the same humanity I beg of you not to drag me away. How strange this seems! Here I am hardly standing on my legs, yet you worry me with your humanity! At the present moment I am good for nothing…. I will not go on any consideration! And for whom should I leave my wife? No…. No.”

Kirilov waved his hands and staggered back.

“Do not … do not ask me,” he continued in a frightened voice. “Excuse me…. By the Thirteenth Volume of the Code I am bound to go, and you have