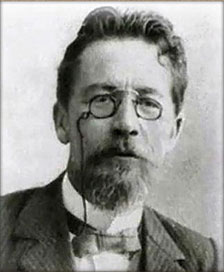

Sleepy, Chekhov Anton

Night. Nursemaid Varka, aged thirteen, rocks the cradle where baby lies, and murmurs almost inaudibly:

“Bayu, bayushki, bayu!

Nurse will sing a song to you!…”

In front of the ikon burns a green lamp; across the room from wall to wall stretches a cord on which hang baby-clothes and a great pair of black trousers. On the ceiling above the lamp shines a great green spot, and the baby-clothes and trousers cast long shadows on the stove, on the cradle, on Varka…. When the lamp flickers, the spot and shadows move as if from a draught. It is stifling. There is a smell of soup and boots.

The child cries. It has long been hoarse and weak from crying, but still it cries, and who can say when it will be comforted P And Varka wants to sleep. Her eyelids droop, her head hangs, her neck pains her…. She can hardly move her eyelids or her lips, and it seems to her that her face is sapless and petrified, and that her head has shrivelled up to the size of a pinhead.

“Bayu, bayushki, bayu!” she murmurs, “Nurse is making pap for you….”

In the stove chirrups a cricket. In the next room behind that door snore Varka’s master and the journeyman Athanasius. The cradle creaks plaintively, Varka murmurs—and the two sounds mingle soothingly in a lullaby sweet to the ears of those who lie in bed. But now the music is only irritating and oppressive, for it inclines to sleep, and sleep is impossible. If Varka, which God forbid, were to go to sleep, her master and mistress would beat her.

The lamp flickers. The green spot and the shadows move about, they pass into the half-open, motionless eyes of Varka, and in her half-awakened brain blend in misty images. She sees dark clouds chasing one another across the sky and crying like the child. And then a wind blows; the clouds vanish; and Varka sees a wide road covered with liquid mud; along the road stretch waggons, men with satchels on their backs crawl along, and shadows move backwards and forwards; on either side through the chilly, thick mist are visible hills. And suddenly the men with the satchels, and the shadows collapse in the liquid mud. “Why is this?” asks Varka. “To sleep, to sleep!” comes the answer. And they sleep soundly, sleep sweetly; and on the telegraph wires perch crows, and cry like the child, and try to awaken them.

“Bayu, bayushki, bayu. Nurse will sing a song to you,” murmurs Varka; and now she sees herself in a dark and stifling cabin.

On the floor lies her dead father, Efim Stepanov. She cannot see him, but she hears him rolling from side to side, and groaning. In his own words he “has had a rupture.” The pain is so intense that he cannot utter a single word, and only inhales air and emits through his lips a drumming sound.

“Bu, bu, bu, bu, bu….”

Mother Pelageya has run to the manor-house to tell the squire that Yefim is dying. She has been gone a long time … will she ever return? Varka lies on the stove, and listens to her father’s “Bu, bu, bu, bu.'” And then someone drives up to the cabin door. It is the doctor, sent from the manor-house where he is staying as a guest. The doctor comes into the hut; in the darkness he is invisible, but Varka can hear him coughing and hear the creaking of the door.

“Bring a light!” he says.

“Bu, bu, bu,” answers Yefim.

Pelageya runs to the stove and searches for a jar of matches. A minute passes in silence. The doctor dives into his pockets and lights a match himself. “Immediately, batiushka, immediately!” cries Pelageya, running out of the cabin. In a minute she returns with a candle end.

Yefim’s cheeks are flushed, his eyes sparkle, and his look is piercing, as if he could see through the doctor and the cabin wall.

“Well, what’s the matter with you?” asks the doctor, bending over him. “Ah! You have been like this long?”

“What’s the matter? The time has come, your honour, to die…. I shall not live any longer….”

“Nonsense…. We’ll soon cure you!”

“As you will, your honour. Thank you humbly … only we understand…. If we must die, we must die….”

Half an hour the doctor spends with Yefim; then he rises and says:

“I can do nothing…. You must go to the hospital; there they will operate on you. You must go at once … without fail! It is late, and they will all be asleep at the hospital … but never mind, I will give you a note…. Do you hear?”

“Batiushka, how can he go to the hospital?” asks Pelageya. “We have no horse.”

“Never mind, I will speak to the squire, he will lend you one.”

The doctor leaves, the light goes out, and again Varka hears: “Bu, bu, bu.” In half an hour someone drives up to the cabin…. This is the cart for Yefim to go to hospital in…. Yefim gets ready and goes….

And now comes a clear and fine morning. Pelageya is not at home; she has gone to the hospital to find out how Yefim is…. There is a child crying, and Varka hears someone singing with her own voice:

“Bayu, bayushki, bayu, Nurse will sing a song to you….”

Pelageya returns, she crosses herself and whispers: “Last night he was better, towards morning he gave his soul to God…. Heavenly kingdom, eternal rest! … They say we brought him too late…. We should have done it sooner….”

Varka goes into the wood, and cries, and suddenly someone slaps her on the nape of the neck with such force that her forehead bangs against a birch tree. She lifts her head, and sees before her her master, the shoemaker.

“What are you doing, scabby?” he asks. “The child is crying and you are asleep.”

He gives her a slap on the ear; and she shakes her head, rocks the cradle, and murmurs her lullaby. The green spot, the shadows from the trousers and the baby-clothes, tremble, wink at her, and soon again possess her brain. Again she sees a road covered with liquid mud. Men with satchels on their backs, and shadows lie down and sleep soundly. When she looks at them Varka passionately desires to sleep; she would lie down with joy; but mother Pelageya comes along and hurries her. They are going into town to seek situations.

“Give me a kopeck for the love of Christ,” says her mother to everyone she meets. “Show the pity of God, merciful gentleman!”

“Give me here the child,” cries a well-known voice. “Give me the child,” repeats the same voice, but this time angrily and sharply. “You are asleep, beast!”

Varka jumps up, and looking around her remembers where she is; there is neither road, nor Pelageya, nor people, but only, standing in the middle of the room, her mistress who has come to feed the child. While the stout, broad-shouldered woman feeds and soothes the baby, Varka stands still, looks at her, and waits till she has finished.

And outside the window the air grows blue, the shadows fade and the green spot on the ceiling pales. It will soon be morning.

“Take it,” says her mistress buttoning her nightdress. “It is crying. The evil eye is upon it!”

Varka takes the child, lays it in the cradle, and again begins rocking. The shadows and the green spot fade away, and there is nothing now to set her brain going. But, as before, she wants to sleep, wants passionately to sleep. Varka lays her head on the edge of the cradle and rocks it with her whole body so as to drive away sleep; but her eyelids droop again, and her head is heavy.

“Varka, light the stove!” rings the voice of her master from behind the door.

That is to say: it is at last time to get up and begin the day’s work. Varka leaves the cradle, and runs to the shed for wood. She is delighted. When she runs or walks she does not feel the want of sleep as badly as when she is sitting down. She brings in wood, lights the stove, and feels how her petrified face is waking up, and how her thoughts are clearing.

“Varka, get ready the samovar!” cries her mistress.

Varka cuts splinters of wood, and has hardly lighted them and laid them in the samovar when another order conies:

“Varka, clean your master’s goloshes!”

Varka sits on the floor, cleans the goloshes, and thinks how delightful it would be to thrust her head into the big, deep golosh, and slumber in it awhile. … And suddenly the golosh grows, swells, and fills the whole room. Varka drops the brush, but immediately shakes her head, distends her eyes, and tries to look at things as if they had not grown and did not move in her eyes.

“Varka, wash the steps outside … the customers will be scandalised!”

Varka cleans the steps, tidies the room, and then lights another stove and runs into the shop. There is much work to be done, and not a moment free.

But nothing is so tiresome as to stand at the kitchen-table and peel potatoes. Varka’s head falls on the table, the potatoes glimmer in her eyes, the knife drops from her hand, and around her bustles her stout, angry mistress with sleeves tucked up, and talks so loudly that her voice rings in Varka’s ears. It is torture, too, to wait at table, to wash up, and to sew. There are moments when she wishes, notwithstanding everything around her, to throw herself on the floor and sleep.

The day