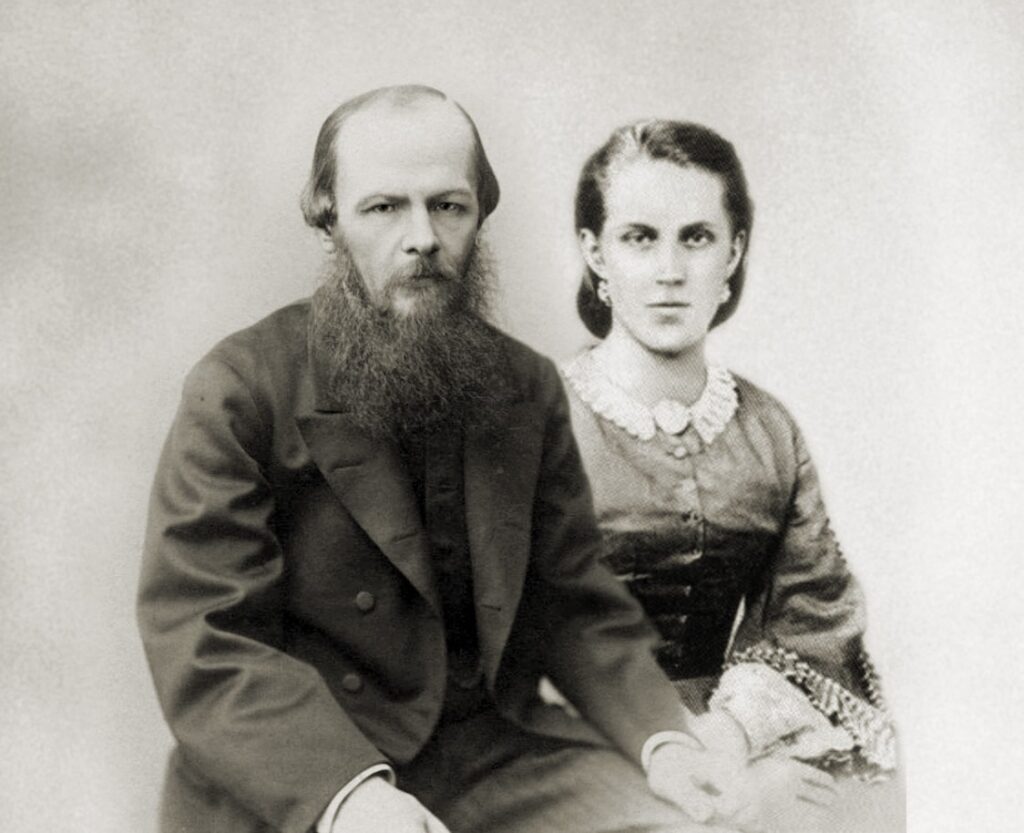

A Few Words about George Sand, Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky

A Few Words about George Sand

George Sand appeared in literature when I was in my early youth, and I am very pleased that it was so long ago because now, more than thirty years later, I can speak almost with complete frankness.

I should note that at the time her sort of thing – novels, I mean – was all that was permitted; all the rest, including virtually every new idea, and those coming from France in particular, was strictly suppressed. Oh, of course it often happened that they weren’t able to pick out such ‘ideas,’ and indeed, where could they learn such a skill? Even Metternich lacked it, never mind those here who tried to imitate him.

And so some ‘shocking things’ would slip through (the whole of Belinsky slipped through, for instance). And then, as if to make up for Belinsky (near the end of the period, in particular) and be on the safe side, they began to forbid almost everything so that, as we know, we were left with little more than pages with blank lines on them.

But novels were still permitted at the beginning, the middle, and even at the very end of the period. It was here, and specifically with George Sand, that the public’s guardians made a very large blunder. Do you remember the verse:

The tomes of Thiers and of Rabaut

He knows, each line by line;

And he, like furious Mirabeau

Hails Liberty divine.

These are very fine verses, exceptionally so, and they will last forever because they have historic significance; but they are all the more precious because they were written by Denis Davydov, the poet, literary figure, and most honorable Russian.

But even if in those days Denis Davydov considered Thiers, of all people (on account of his history of the revolution, of course) as dangerous and put him in a verse along with some Rabaut fellow (such a man also existed, it seems, but I don’t know him), then there surely could not have been much that was permitted officially then. And what was the result?

The whole rush of new ideas that came through the novels of the time served exactly the same ends, and perhaps by the standards of the day in an even more ‘dangerous’ form, since there probably were not too many lovers of Rabaut, but there were thousands who loved George Sand.

It should also be noted here that, despite all the Magnitskys and the Liprandis, ever since the eighteenth century people in Russia have at once learned about every intellectual movement in Europe, and these ideas have been at once passed down from the higher levels of our intellectuals to the mass of those taking even a slight interest in things and making some effort to think. This was precisely what happened with the European movement of the 1830s.

Very quickly, right from the beginning of the thirties, we learned of this immense movement of European literatures. The names of the many newly fledged orators, historians, publicists, and professors became known. We even knew, though incompletely and superficially, the direction in which this movement was heading. And this movement manifested itself with particular passion in art – in the novel and above all in George Sand. It is true that Senkovsky and Bulgarin had warned the public about George Sand even before her novels appeared in Russian.

They tried to frighten Russian ladies, in particular, by telling them that she wore trousers; they tried to frighten people by saying she was depraved; they wanted to ridicule her. Senkovsky, who himself had been planning to translate George Sand in his magazine Reader’s Library, began calling her Mrs. Yegor Sand in print and, it seems, was truly pleased with his witticism. Later on, in 1848, Bulgarin wrote in The Northern Bee that she indulged in daily drinking bouts with Pierre Leroux somewhere near the city gates and participated in ‘Athenian evenings’ at the Ministry of the Interior; these evenings were supposedly hosted by the Minister himself, the bandit Ledru-Rollin.

I read this myself and re-member it very clearly. But at that time, in 1848, nearly the whole of our reading public knew George Sand, and no one believed Bulgarin. She appeared in Russian translation for the first time around the middle of the thirties. It’s a pity that I don’t recall when her first work was translated into Russian and which it was; but the impression it made must have been all the more startling.

I think that the chaste, sublime purity of her characters and ideals and the modest charm of the severe, restrained tone of her narrative must have struck everyone then as it did me, still a youth – and this was the woman who went about in trousers engaging in debauchery! I was sixteen, I think, when I read her tale L’Uscoque for the first time; it is one of the most charming among her early works.

Afterward, I recall, I had a fever all night long. I think I am right in saying, by my recollection at least, that George Sand for some years held almost the first place in Russia among the whole Pleiad of new writers who had suddenly become famous and created such a stir all over Europe. Even Dickens, who appeared in Russia at virtually the same time, was perhaps not as popular among our readers as she.

I am not including Balzac, who arrived before her but who produced works such as Eugénie Grandet and Père Goriot in the thirties (and to whom Belinsky was so unfair when he completely overlooked Balzac’s significance in French literature). However, I say all this not to make any sort of critical evaluation but purely and simply to recall the tastes of the mass of Russian readers at that time and the direct impression these readers received. What mattered most was that the reader was able to derive, even from her novels, all the things the guardians were trying so hard to keep from them.

At least in the mid-forties the ordinary Russian reader knew, if only incompletely, that George Sand was one of the brightest, most consistent, and most upright representatives of the group of Western ‘new people’ of the time, who, with their arrival on the scene, began to refute directly those ‘positive’ achievements which marked the end of the bloody French (or rather, European) revolution of the preceding century. With the end of the revolution (after Napoleon I) there were fresh attempts to express new aspirations and new ideals.

The most advanced minds understood all too well that this had only been despotism in a new form and that all that had happened was ‘ôte toi de là que je m’y mette’; that the new conquerors of the world, the bourgeoisie, turned out to be perhaps even worse than the previous despots, the nobility; that Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité proved to be only a ringing slogan and nothing more. Moreover, certain doctrines appeared which transformed such ringing slogans into utterly impossible ones.

The conquerors now pronounced or recalled these three sacramental words in a tone of mockery; even science, through its brilliant representatives (economists) came with what seemed to be its new word to support this mocking attitude and to condemn the utopian significance of these three words for which so much blood had been shed. So it was that alongside the triumphant conquerors there began to appear despondent and mournful faces that frightened the victors.

At this very same time a truly new word was pronounced and hope was reborn: people appeared who proclaimed directly that it had been vain and wrong to stop the advancement of the cause; that nothing had been achieved by the change of political conquerors; that the cause must be taken up again; that the renewal of humanity must be radical and social. Oh, of course, along with these solemn exclamations there came a host of views that were most pernicious and distorted, but the most important thing was that hope began to shine forth once more and faith again began to be regenerated.

The history of this movement is well known; it continues even now and, it seems, has no intention of coming to a halt. I have no intention whatever of speaking either for or against it here, but I wanted only to define George Sand’s real place within that movement.

We must look for her place at the very beginning of the movement. People who met her in Europe then said that she was propounding a new status for women and foreseeing the ‘rights of the free wife’ (this is what Senkovsky said about her). But that was not quite correct, because she was by no means preaching only about women and never invented any notion of a ‘free wife.’ George Sand belonged to the whole movement and was not merely sermonizing on women’s rights.

It is true that as a woman she naturally preferred portraying heroines to heroes; and of course women all over the world should put on mourning in her memory, because one of the most elevated and beautiful of their representatives has died. She was, besides, a woman of almost unprecedented intelligence and talent – a name that has gone down in history, a name that is destined not to be forgotten and not to disappear from European humanity.

As far as her heroines are concerned, I repeat that from my very first reading at the age of sixteen I was amazed by the strangeness of the contradiction between what was written and said about her