Anna Karenina as a Fact of Special Importance, Fyodor Dostoevsky

Anna Karenina as a Fact of Special Importance

And so, at that very time – one evening last spring, that is – I happened to meet one of my favourite writers on the street. We meet rarely, once every few months, and somehow always by chance on the street. He is one of the most prominent among those five or six writers who are usually called the ‘Pleiade,’ for some reason. The critics, at least, have followed the readers and have set them apart and placed them above all the other writers; this has been the case for some time now – still the same group of five, and the Pleiade’s membership does not increase. I enjoy meeting this dear novelist of whom I am so fond; I enjoy showing him, among other things, that I think he is quite wrong in saying that he has become old-fashioned and will write nothing more.

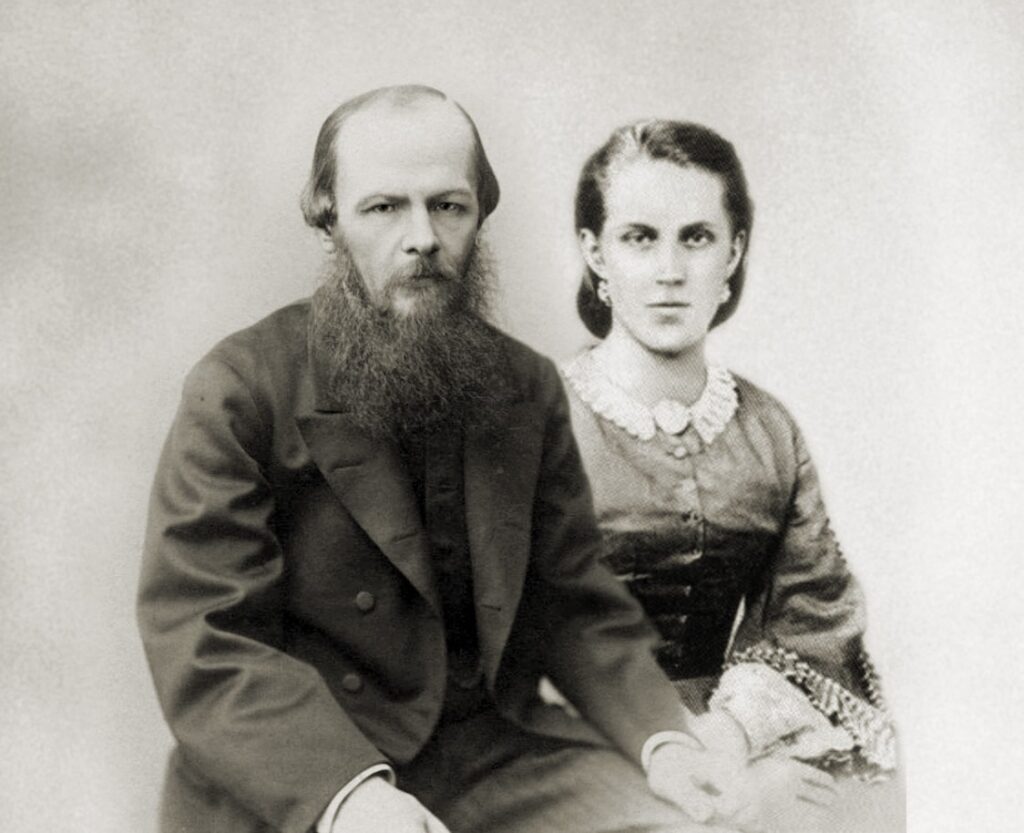

I always bring away some subtle and perceptive insight from our brief conversations. We had much to talk about this time, for the war had already begun. But he at once began speaking directly about Anna Karenina. I had also just finished reading part seven, with which the novel had concluded in The Russian Messenger. My interlocutor does not look like a man of strong enthusiasms. On this occasion, however, I was struck by the firmness and passionate insistence of his views on Anna Karenina.

‘It’s something unprecedented, a first. Are there any of our writers who could rival it? Could anyone imagine anything like it in Europe? Is there any work in all their literatures over the past years, and even much earlier, that could stand next to it?’

What struck me most in this verdict, which I myself shared completely, was that the mention of Europe was so relevant to those very questions and problems that were arising of their own accord in the minds of so many. The book at once took on, in my eyes, the dimensions of a fact that could give Europe an answer on our behalf, that long-sought-after fact we could show to Europe. Of course, people will howl and scoff that this is only a work of literature, some sort of novel, and that it’s absurd to exaggerate this way and go off to Europe carrying only a novel. I know that people will howl and scoff, but don’t worry: I’m not exaggerating and am looking at the matter soberly: I know very well that this is still only a novel and that it’s but a tiny drop of what we need; but the main thing for me here is that this drop already exists, it is given, it really and truly does exist; and so, if we already have it, if the Russian genius could give birth to this fact, then it is not doomed to impotence and can create; it can provide something of its own, it can begin its own word and finish uttering it when the times and seasons come to pass.

And besides, this is much more than a mere drop. Oh, I’m not exaggerating here either: I know very well that you won’t find, either in any individual member of this Pleiade or in the whole Pleiade together, anything that can be called, strictly speaking, a creative force of true genius. In our entire literature there have been but three unquestioned geniuses who had an unquestionably ‘new word’ to utter, and these three were Lomonosov, Pushkin, and, in part, Gogol. This whole Pleiade (including the author of Anna Karenina) emerged directly from Pushkin, one of the greatest of Russians who, however, is still far from being interpreted and understood properly. There are two principal ideas in Pushkin, and they both contain a model of the whole of Russia’s future mission and goal, and therefore of our whole future destiny.

The first is Russia’s universality, her capacity to respond, and the genuine, unquestioned, profound kinship of her genius with the geniuses of all ages and all peoples of the world. Pushkin does not merely call our attention to this idea or convey it in the form of a doctrine or theory or as a cherished hope or prophecy; he carries it out in practice, embodies it, and proves it forever in his brilliant creations. He is a man of the ancient world; he is also a German and an Englishman, deeply aware of his own animating spirit and the anguish of his aspirations (‘A Feast in Time of Plague’); he is a poet of the East. To all these peoples he stated and proclaimed that the Russian genius knew them, has understood them, has touched them like a brother, that it can fully reincarnate itself in them, that to the Russian spirit alone is given universality and the future mission to comprehend and to unify all the diverse nationalities and to eliminate all their contradictions.

Pushkin’s other idea was his turning to the People and investing his hopes in their strength alone, his pledge that in the People and in the People alone will we fully discover our whole Russian genius and our consciousness of its mission. And here, too, Pushkin did not merely point out a fact but was also the first to realise the fact in practice. It was only with him that we began our real, conscious turn to the People, something that had been inconceivable before him ever since Peter’s reforms. The whole Pleiade of today have worked only along his lines; after Pushkin no one has said anything new. All their sources were in him, and he pointed them out. And besides, the Pleiade has elaborated only the tiniest part of what he pointed out. What they have done, however, has been done with such largess of talent, with such depth and distinction, that Pushkin would naturally have acknowledged them.

The idea behind Anna Karenina, of course, is nothing new or unheard of in Russia. Instead of this novel we could, of course, show Europe the source – Pushkin himself, that is – as the strongest, most vivid, and most incontestable proof of the independence of the Russian genius and its rights to a great, worldwide, pan-human and all-unifying significance in the future. (Alas, no matter how we tried to show them that, Europe will not read our writers for a long time yet; and if Europe does begin to read them, the Europeans will not be able to understand and appreciate them for a long time. Indeed, they are utterly unable to appreciate our writers, not because of insufficient capacity, but because for them we are an entirely different world, just as if we had come down from the moon, so that it is difficult for them even to admit the fact that we exist.

All this I know, and I speak of ‘showing Europe’ only in the sense of our own conviction of our right to independence vis-à-vis Europe.) Nevertheless, Anna Karenina is perfection as a work of art that appeared at just the right moment and as a work to which nothing in the European literatures of this era can compare; and, in the second place, the novel’s idea also contains something of ours, something truly our own, namely that very thing which constitutes our distinctness from the European world, the thing which constitutes our ‘new word,’ or at least its beginnings – just the kind of word one cannot hear in Europe, yet one that Europe still so badly needs, despite all her pride.

I cannot embark upon literary criticism here and will say only a few things. Anna Karenina expresses a view of human guilt and transgression. People are shown living under abnormal conditions. Evil existed before they did. Caught up in a whirl of falsities, people transgress and are doomed to destruction. As you can see, it is one of the oldest and most popular of European themes. But how is such a problem solved in Europe? Generally in Europe there are two ways of solving it.

Solution number one: the law has been given, recorded, formulated, and put together through the course of millennia. Good and evil have been defined and weighed, their extent and degree have been determined historically by humanity’s wise men, by unceasing work on the human soul, and by working out, in a very scientific manner, the extent of the forces that unite people in a society.

One is commanded to follow this elaborated code of laws blindly. He who does not follow it, he who transgresses, pays with his freedom, his property, or his life; he pays literally and cruelly. ‘I know,’ says their civilisation, ‘that this is blind and cruel and impossible, since we are not able to work out the ultimate formula for humanity while we are still at the midpoint of its journey; but since we have no other solution, it follows that we must hold to that which is written, and hold to it literally and cruelly. Without it, things would be even worse.

At the same time, despite all the abnormality and absurdity of the structure we call our great European civilisation, let the forces of the human spirit remain healthy and intact; let society not be shaken in its faith that it is moving toward perfection; let no one dare think that the idea of the beautiful and sublime has been obscured, that the concepts of good and evil are being distorted and twisted, that convention is constantly taking the place of the healthy norm, that simplicity