Naturally, Kircher understood, as Bacon and others had, that ideograms were universal characters referring to ideas and not, alphabetically, to sounds. But at this point he took a curious position. While the hieroglyphs were of divine origin because they depicted the unknown and mysterious essence of things, Chinese ideograms referred clearly and unambiguously to precise ideas. In this sense they were corrupted hieroglyphs, which had lost their divine power and become mere practical tools. As Kircher said, when a hieroglyphic represents an animal that, in its turn, represents the sun, this sun is not only the celestial body but also the Sun as a spiritual archetype. Because the Chinese ideogram referred only to the sun as a star, it was a degenerate hieroglyph.

In the following century, in an atmosphere of neopagan sinophilia, the rationalistic criticism of Rousseau, Warburton, and the Encyclopédie of Diderot and D’Alembert turned the entire matter upside down: Chinese ideograms were better than Egyptian hieroglyphics because they were clear, precise, and unambiguous, while the hieroglyphs were vague and imprecise. But for Kircher such vagueness, the multiinterpretablity of hieroglyphics, was a proof of their divine origin, while the human precision of the ideogram was proof that true Egyptian wisdom (of which Christian wisdom was considered the direct heir) in coming to China was corrupted by the devil.

In order better to clarify Kircher’s position, I must tell another story, one concerning the first description of the newly discovered lands of America, in particular the Mexican Maya and Aztec civilizations.

In 1590 a Historia natural y moral de las Indias was published by Father José de Acosta, who sought to demonstrate that the native inhabitants of America had a cultural tradition and outstanding intellectual abilities. To prove this, he described the pictographic nature of Mexican writing, showing that it had the same nature as Chinese. This was a courageous position because other authors had insisted on the subhuman nature of the Amerindians, and a work by Diego de Landa entitled Relacion de las cosas de Yucatan showed the diabolical nature of their writing.

Now it happens that Kircher (in Oedypus) shared the opinion of Diego de Landa and provided proof of the inferiority of Mexican writing. Their system was not made up of hieroglyphs, because, contrary to Egyptian hieroglyphs, the Mexican signs did not refer to sacred mysteries; neither were they ideograms in the Chinese sense, because they did not refer to general ideas but to singular facts. Instead, they were mere pictograms and thus not an example of universal language, because images referring—as mnemonic devices—to single facts can be understood only by those who already know these facts.

Recent research has proved that the Amerindians’ pictograms were in fact an instance of a very flexible pictoral language, also able to express abstract ideas. It really is a pity that Western scholars finally discovered this only some centuries after we had destroyed those civilizations on the grounds of their semiotical inferiority.

But this is not only a case of new discoveries being influenced by backround books; it is a disquieting instance of the influence of political and economic motivations on the reading of newly discovered books.

Ancient Egypt had disappeared, and its whole wisdom had become part of the Christian civilization (at least, according to the Kircherian utopia); its writing was thus considered sacred and magical. Amerindians were people to be colonized; their religion had to be destroyed along with their political system (and as a matter of fact at the time Kircher was writing, both had already been destroyed). To justify such a violent transformation of a country and a culture, it was useful to demonstrate that their writing had no philosophical interest.

China, on the contrary, was a powerful empire with a developed culture; at that time, at least, the European states had no intention to subjugate it. China Illustrata, however, appeared under the auspices of Emperor Leopold I, whose dominions faced eastward and to whom Christian communities of the Asiatic Near East looked for protection (for instance, to please the Armenians it was suggested that the Holy Roman Emperor had a mission to rebuild the fabled but decaying temple of King Cyrus). Many of the Jesuit missionaries, such as Grueber and Martini, came from Central Europe, and Austria considered itself the great light of Eastern Christianity. In some way, the great empire of China had to be involved in such an ambitious project. Thus Kircher—who played a crucial part in the quest for this utopia—constructed a whole spiritual history of China in which Christianity is claimed to have been an abiding force there since the early centuries after Christ. Even the connection he posited between China and Egypt was part of the imperial dream. China was presented not as an unknown barbarian to be defeated but as a prodigal son who should return to the home of the common Father.

Thus the problem was to deal with Chinese, to establish not a conquest but at least an exchange relationship, an exchange, however, in which Europe would play a major role, since it was the bearer of the true religion. The Mexicans, with their diabolical way of writing, had to be converted against their will; the Chinese, whose writing was neither as venerable as Egyptian nor as diabolical as Mexican, had to be peacefully and rationally persuaded of the superiority of Western thought. The Kircherian classification of hieroglyphics, ideograms, and pictograms mirrored the difference between two ways of interacting with exotic civilizations.

I have repeated the whole story because it seems to me that, once again, Kircher was ideally going to China not to discover something different but to find again and again what he already knew and what had been told him by a series of background books. Instead of trying to understand differences Kircher looked for identities.

Naturally, everything depends on one’s background books and on what one is looking for. Let me finish with another story. At the end of the seventeenth century Leibniz was still looking for a universal language. But he was no longer pursuing the utopia of a perfect mystical tongue. Instead, he was searching for a mathematical language by virtue of which scholars, when debating a problem, could sit around a table, make some logical calculuses, and find a common truth. In short, he was a forerunner, or rather the founder, of contemporary formal logic.

His background books were different from those of Kircher, but his way of interpreting an unfamiliar culture was not so different. Profoundly fascinated by China (he devoted many writings to it), he thought that “by singular will of destiny” the two greatest civilizations of humanity were located at the two extremities of the Eurasian continent: Europe and China. He said that China was challenging Europe in the fight for primacy and that the battle was won now by one and now by the other of the two rivals. China was better than Europe as far as the elegance of life and the principles of ethics and politics were concerned, while Europe had achieved primacy in abstract mathematical sciences and metaphysics. Clearly, this was a man who did not harbor thoughts of political conquest or religious conversion but on the contrary was inspired by ideals of loyal and respectful mutual exchange of experiences.

After Leibniz had published a collection of documents on China (Novissima Sinica, 1679), Father Joachim Bouvet, just coming back from China, wrote him a letter in which he describes the I Ching, the now all-too-famous Chinese book on which many New Age fans are playing Olympic games of free and irresponsible interpretation. Father Bouvet thought that this book contained the fundamental principles of Chinese tradition. At the same time Leibniz was working on binary calculus, the mathematical calculus that proceeds by 0 and 1 and is still used today for programming computers. Leibniz was convinced that this calculus had a metaphysical foundation because it reflects the dialectic between God and Nothingness. Bouvet thought that binary calculus was perfectly represented by the structure of the hexagrams that appeared in the I Ching, and he sent Leibniz a reproduction of the system.

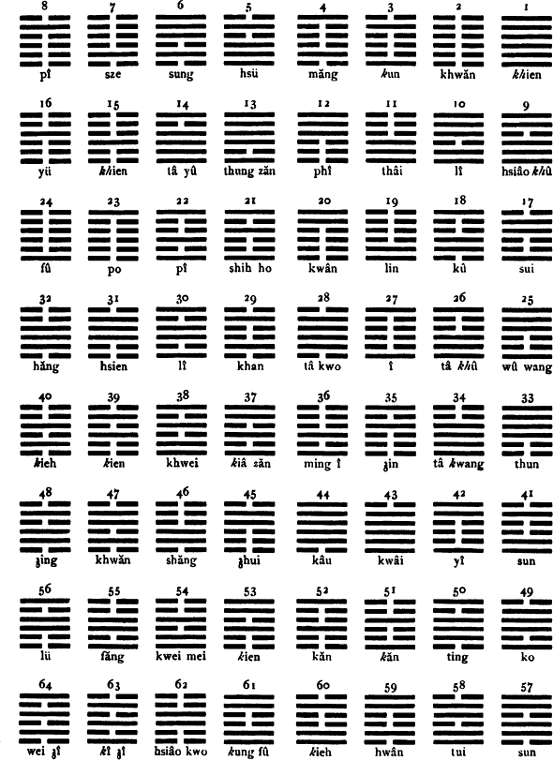

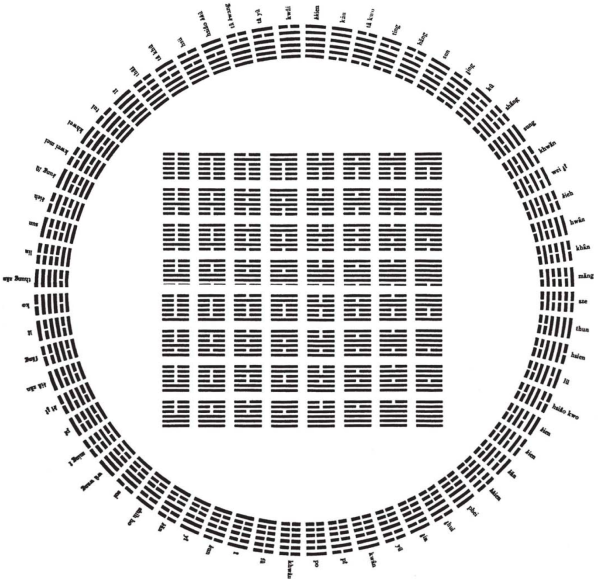

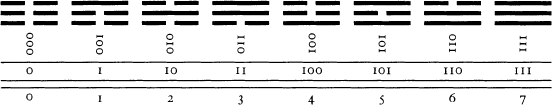

Now, in the I Ching the hexagrams follow the order (called Weng-Wang order) shown in figure 1, to be read horizontally from right to left. Bouvet, however, sent Leibniz a different representation (the Fu-hsi order), that is, the one reproduced in the central square of figure 2. It was easy for Leibniz, reading them horizontally (but from left to right!) to recognize in these representations a diagrammatic reproduction of the progression of natural numbers in binary digits, as he demonstrated in his Explication de l’arithmétique binaire (1705) (see figure 3). Thus—following Leibniz—we could say today that the I Ching contains the principles of Boolean algebra.

FIGURE 1 The Hexagrams in the Weng-Wang Order

FIGURE 2 The Hexagrams in the Fu-hsi Order

FIGURE 3 The Presentation of Binary Calculus in Leibniz’s Explication de l’arithmétique binaire

This is another case in which someone discovers something different and tries to see it as absolutely analogous to what he already knows. The I Ching was important for its divinatory contents, but for Leibniz it becomes further evidence in proving the universal value of his formal calculus (and in a letter to Father Bouvet he suggests