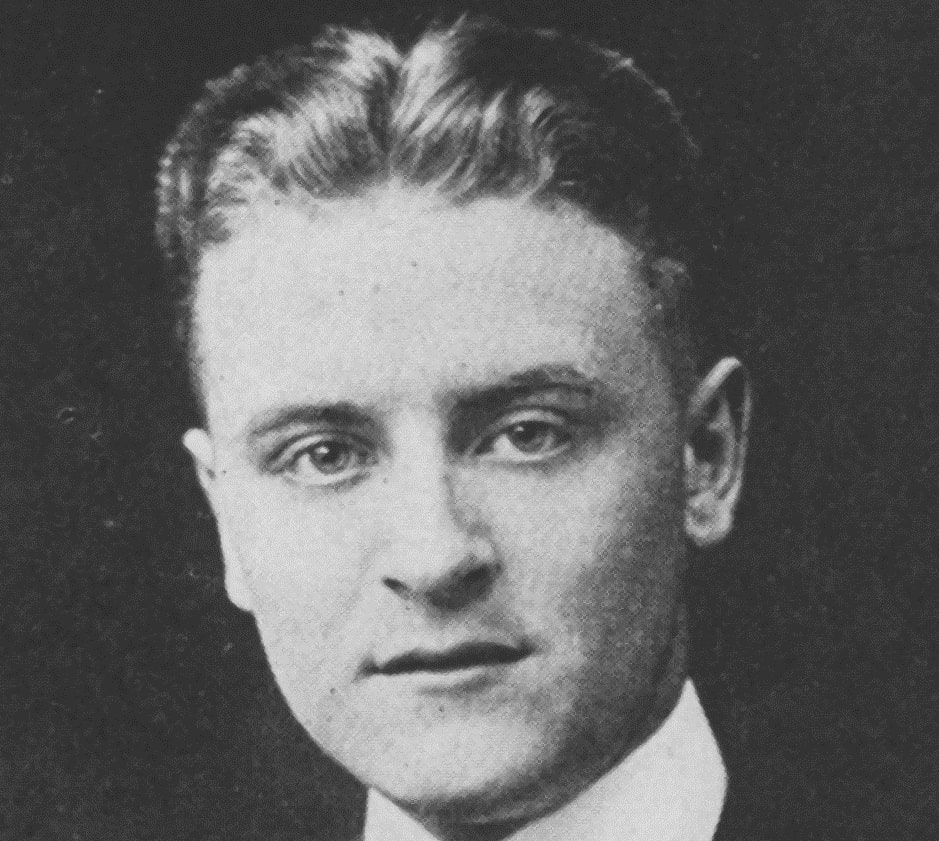

A Freeze-Out, F. Scott Fitzgerald

I

Here and there in a sunless corner skulked a little snow under a veil of coal specks, but the men taking down storm windows were laboring in shirt sleeves and the turf was becoming firm underfoot.

In the streets, dresses dyed after fruit, leaf and flower emerged from beneath the shed somber skins of animals; now only a few old men wore mousy caps pulled down over their ears.

That was the day Forrest Winslow forgot the long fret of the past winter as one forgets inevitable afflictions, sickness, and war, and turned with blind confidence toward the summer, thinking he already recognized in it all the summers of the past—the golfing, sailing, swimming summers.

For eight years Forrest had gone East to school and then to college; now he worked for his father in a large Minnesota city.

He was handsome, popular and rather spoiled in a conservative way, and so the past year had been a comedown.

The discrimination that had picked Scroll and Key at New Haven was applied to sorting furs; the hand that had signed the Junior Prom expense checks had since rocked in a sling for two months with mild dermatitis venenata.

After work, Forrest found no surcease in the girls with whom he had grown up. On the contrary, the news of a stranger within the tribe stimulated him and during the transit of a popular visitor he displayed a convulsive activity. So far, nothing had happened; but here was summer.

On the day spring broke through and summer broke through—it is much the same thing in Minnesota—Forrest stopped his coupй in front of a music store and took his pleasant vanity inside.

As he said to the clerk, “I want some records,” a little bomb of excitement exploded in his larynx, causing an unfamiliar and almost painful vacuum in his upper diaphragm.

The unexpected detonation was caused by the sight of a corn-colored girl who was being waited on across the counter.

She was a stalk of ripe corn, but bound not as cereals are but as a rare first edition, with all the binder’s art. She was lovely and expensive, and about nineteen, and he had never seen her before.

She looked at him for just an unnecessary moment too long, with so much self-confidence that he felt his own rush out and away to join hers—“…from him that hath not shall be taken away even that which he hath.” Then her head swayed forward and she resumed her inspection of a catalogue.

Forrest looked at the list a friend had sent him from New York. Unfortunately, the first title was: “When Voo-do-o-do Meets Boop-boop-a-doop, There’ll Soon be a Hot-Cha-Cha.” Forrest read it with horror. He could scarcely believe a title could be so repulsive.

Meanwhile the girl was asking: “Isn’t there a record of Prokofiev’s ’Fils Prodigue’?”

“I’ll see, madam.” The saleswoman turned to Forrest.

“’When Voo—’” Forrest began, and then repeated, “’When Voo—’”

There was no use; he couldn’t say it in front of that nymph of the harvest across the table.

“Never mind that one,” he said quickly. “Give me ’Huggable—’”

Again he broke off.

“’Huggable, Kissable You’?” suggested the clerk helpfully, and her assurance that it was very nice suggested a humiliating community of taste.

“I want Stravinsky’s ’Fire Bird,’” said the other customer, “and this album of Chopin waltzes.”

Forrest ran his eye hastily down the rest of his list: “Digga Diggity,” “Ever So Goosy,” “Bunkey Doodle I Do.”

“Anybody would take me for a moron,” he thought. He crumpled up the list and fought for air—his own kind of air, the air of casual superiority.

“I’d like,” he said coldly, “Beethoven’s ’Moonlight Sonata.’”

There was a record of it at home, but it didn’t matter. It gave him the right to glance at the girl again and again.

Life became interesting; she was the loveliest concoction; it would be easy to trace her. With the “Moonlight Sonata” wrapped face to face with “Huggable, Kissable You,” Forrest quitted the shop.

There was a new book store down the street, and here also he entered, as if books and records could fill the vacuum that spring was making in his heart.

As he looked among the lifeless words of many titles together, he was wondering how soon he could find her, and what then.

“I’d like a hard-boiled detective story,” he said.

A weary young man shook his head with patient reproof; simultaneously, a spring draft from the door blew in with it the familiar glow of cereal hair.

“We don’t carry detective stories or stuff like that,” said the young man in an unnecessarily loud voice. “I imagine you’ll find it at a department store.”

“I thought you carried books,” said Forrest feebly.

“Books, yes, but not that kind.” The young man turned to wait on his other customer.

As Forrest stalked out, passing within the radius of the girl’s perfume, he heard her ask:

“Have you got anything of Louis Arragon’s, either in French or in translation?”

“She’s just showing off,” he thought angrily. “They skip right from Peter Rabbit to Marcel Proust these days.”

Outside, parked just behind his own adequate coupй, he found an enormous silver-colored roadster of English make and custom design. Disturbed, even upset, he drove homeward through the moist, golden afternoon.

The Winslows lived in an old, wide-verandaed house on Crest Avenue—Forrest’s father and mother, his great-grandmother and his sister Eleanor.

They were solid people as that phrase goes since the war. Old Mrs. Forrest was entirely solid; with convictions based on a way of life that had worked for eighty-four years.

She was a character in the city; she remembered the Sioux war and she had been in Stillwater the day the James brothers shot up the main street.

Her own children were dead and she looked on these remoter descendants from a distance, oblivious of the forces that had formed them. She understood that the Civil War and the opening up of the West were forces, while the free-silver movement and the World War had reached her only as news.

But she knew that her father, killed at Cold Harbor, and her husband, the merchant, were larger in scale than her son or her grandson.

People who tried to explain contemporary phenomena to her seemed, to her, to be talking against the evidence of their own senses. Yet she was not atrophied; last summer she had traveled over half of Europe with only a maid.

Forrest’s father and mother were something else again. They had been in the susceptible middle thirties when the cocktail party and its concomitants arrived in 1921.

They were divided people, leaning forward and backward. Issues that presented no difficulty to Mrs. Forrest caused them painful heat and agitation. Such an issue arose before they had been five minutes at table that night.

“Do you know the Rikkers are coming back?” said Mrs. Winslow. “They’ve taken the Warner house.” She was a woman with many uncertainties, which she concealed from herself by expressing her opinions very slowly and thoughtfully, to convince her own ears.

“It’s a wonder Dan Warner would rent them his house. I suppose Cathy thinks everybody will fall all over themselves.”

“What Cathy?” asked old Mrs. Forrest.

“She was Cathy Chase. Her father was Reynold Chase. She and her husband are coming back here.”

“Oh, yes.”

“I scarcely knew her,” continued Mrs. Winslow, “but I know that when they were in Washington they were pointedly rude to everyone from Minnesota—went out of their way.

Mary Cowan was spending a winter there, and she invited Cathy to lunch or tea at least half a dozen times. Cathy never appeared.”

“I could beat that record,” said Pierce Winslow. “Mary Cowan could invite me a hundred times and I wouldn’t go.”

“Anyhow,” pursued his wife slowly, “in view of all the scandal, it’s just asking for the cold shoulder to come out here.”

“They’re asking for it, all right,” said Winslow. He was a Southerner, well liked in the city, where he had lived for thirty years.

“Walter Hannan came in my office this morning and wanted me to second Rikker for the Kennemore Club. I said: ’Walter, I’d rather second Al Capone.’ What’s more, Rikker’ll get into the Kennemore Club over my dead body.”

“Walter had his nerve. What’s Chauncey Rikker to you? It’ll be hard to get anyone to second him.”

“Who are they?” Eleanor asked. “Somebody awful?”

She was eighteen and a dйbutante. Her current appearances at home were so rare and brief that she viewed such table topics with as much detachment as her great-grandmother.

“Cathy was a girl here; she was younger then I was, but I remember that she was always considered fast. Her husband, Chauncey Rikker, came from some little town upstate.”

“What did they do that was so awful?”

“Rikker went bankrupt and left town,” said her father. “There were a lot of ugly stories. Then he went to Washington and got mixed up in the alien-property scandal; and then he got in trouble in New York—he was in the bucket-shop business—but he skipped out to Europe.

After a few years the chief Government witness died and he came back to America. They got him for a few months for contempt of court.”

He expanded into eloquent irony: “And now, with true patriotism, he comes back to his beautiful Minnesota, a product of its lovely woods, its rolling wheat fields—”

Forrest called him impatiently: “Where do you get that, father? When did two Kentuckians ever win Nobel prizes in the same year? And how about an upstate boy named Lind—”

“Have the Rikkers any children?” Eleanor asked.

“I think Cathy has a daughter about your age, and a boy about sixteen.”

Forrest