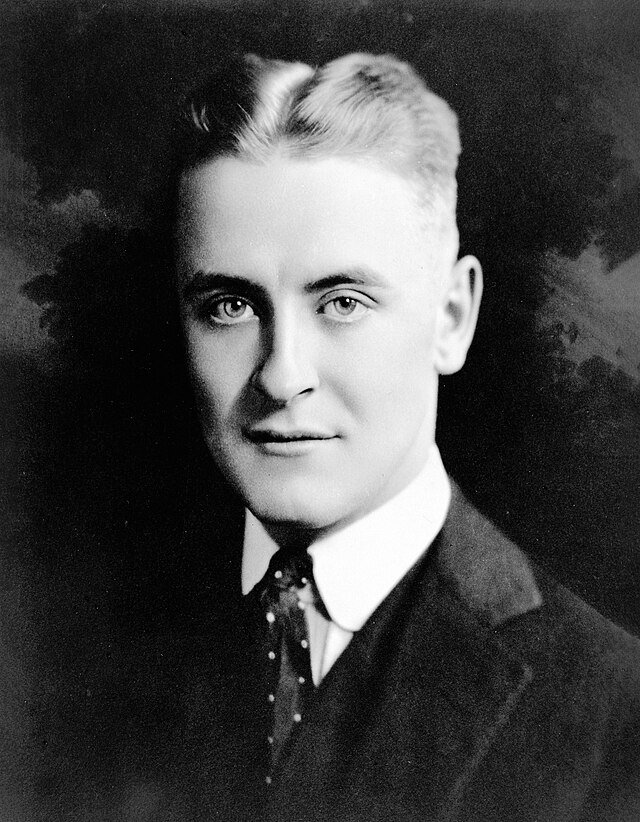

Cyclone in Silent Land, F. Scott Fitzgerald

Unpublished Fitzgerald story featuring the nurse “Trouble.” The ex-chorus girl turned nursing student.

Glenola McClurg and her adventures with the young doctor Dick Wheelock was a character that Fitzgerald hoped to have in a series of recurring stories for The Saturday Evening Post.

Unfortunately, the present story, his first attempt, was rejected by the magazine which only reluctantly accepted a second, vastly different version titled “Trouble” before advising the author to drop the character.

I

“Why don’t you just pull the socks off? Get an orderly to help you. Good Lord, that’s what I’d do if a patient kept me up all night with idiotic calls.”

“I’ve thought of that,” Bill said. “I’ve tried to think of everything in my whole medical training. But this man is a big shot—”

“You’re not supposed to pay any attention to that—”

“I don’t mean just rich—I mean he has the air of being a big shot in his own profession like Dandy and Kelly in ours—”

“You’re nervous,” said the other interne. “How’re you going to lecture to those girls in two hours?”

“I don’t know.”

“Oh, lie down and get some sleep. I’ve got to get over to the bacteriology lab and I want to get some breakfast first.”

“Sleep!” Bill exclaimed. “I’ve tried it plenty times tonight. Soon as I get my eyes closed that ward rings.”

“Well, do you want some breakfast?”

Bill was dressed—or rather hadn’t been undressed all night. Harris had finished dressing and after adjusting his necktie suggested to Bill Craig:

“Change your whites. You’re mussy.”

Bill groaned.

“I’ve changed them five times in two days. You think I run a private laundry?”

Harris went to a bureau.

“Put on these—they ought to fit—I used yours plenty times last fall. Come on now. Slip into these—breakfast is on the schedule.”

Bill pulled himself together and started living on his nervous system—enough to live on, for it was solid and he was a good physical specimen with a tradition of many doctors behind him; he struggled into the proffered whites.

“Let’s go. But I think I ought to leave some word for this man on the way.”

“Oh, forget it. Come on—we’ll have breakfast. A man that won’t take off his socks!”

But Bill was still fretted as they went out into the corridor.

“I don’t feel quite comfortable. After all the poor guy hasn’t got anybody to depend on except me.”

“You’re going sentimental.”

“Maybe.”

And now up the corridor came Trouble, Trouble so white, so lovely, that it didn’t identify itself immediately as such. It was sheer trouble. It was the essence of trouble—trouble personified, challenging…

… trouble.

Starting to smile a hundred feet away it came along like a flying cloud—began to pass the internes, stopped, wheeled smart as the military, came up to both of them and figuratively pressed against them. All she said was:

“Good morning, Dr. Craig, morning Dr. Machen.”

Then Trouble, knowing she’d done it, leaned back against the wall, conscious, oh completely conscious of having stamped herself vividly on their masculine clay.

It was a curious sort of American beauty, very difficult to show the charm of it because it was the blend of many races.

It was not blonde, nor was it dark; it had a pride of its own; it was rather like the autumn page from the kitchen calendars of thirty years ago with blue instead of brown October eyes. It went under the registered name of Benjamina Rosalyn—Trouble to her friends.

What more did she look like? To the two internes she looked like a lovely muffin, like the cream going into the coffee in the breakfast room.

This all happened in a moment. Then they went on, Bill insisting after all on stopping at the desk and leaving a note as to where he could be found.

“You’re going nuts about that old man,” Harris warned him. “Why don’t you concentrate on clipping his sympathetic nerves like we’re going to do tomorrow? That’s when he really will need help.”

Miss Harte at the desk was saying:

“It’s a call for you from Ward 4, Dr. Craig. Do you want to take it?”

Harris pulled him toward the dining room but Bill said:

“I’ll take it.”

“You’ve got to lecture in half an hour. You’ll miss your breakfast.”

“Never mind. It’s from Room 1B, isn’t it?”

“Yes, Dr. Craig.”

“Gosh, I’d like to hear your lecture to those probationers,” said Harris disgustedly. “But go on—boys will be boys.”

Bill went into 1B on Ward 4. Mr. Polk Johnston, robust and fifty, sat up in bed.

“So you came,” he said gruffly. “They said you probably wouldn’t but you’re the only person here I can trust—you and that little nurse they call Trouble.”

“She’s not a nurse—she’s only a probationer.”

“Well, she looks like a nurse to me. Say, what I called you here for is to know the name of that operation again.”

“It’s called sympathectomy. By the way, Mr. Johnston—let me take that sock off, will you?”

“No,” the man roared. “I thought you were doctors, not chiropodists. I’ll keep my sock on. If you think I’m crazy how did I make my money?”

“Nobody thinks you’re crazy. Now Mr. Johnston, I’ve got to go along and lecture—I’ll be back.”

“How soon?”

“Say an hour.”

“All right then. Send the little girl.”

“She’ll be at the lecture too.” Bill escaped on the old man’s groan.

The hospital was housed in three buildings connected by cloisters of plane trees and bushes.

When Bill came outdoors on his way to the classroom he stopped for a moment, leaning against a protrudent branch. What was this feeling of intense irritation—maybe he was never meant to be a doctor.

“But I’ve got the physique for it,” he thought. “I’ve got the courage—I hope I have. I’ve got the intelligence. Why can’t I kill this nervous business?”

He went on, pushing a bush out of his way.

“I’ve got to face these girls as something. Pull yourself up, Bill, my boy. You were hand picked for this lecture job and they’re going to be plenty other patients to run you ragged.”

From where he was in the green cloister he could see the probationers flocking into class, twenty of them, and he took advantage of the fact to organize the few words that would inaugurate his lecture while they examined the rabbit.

The rabbit was anesthetized, the heart exposed and ready to respond to adrenalin, to digitalis, to strychnine. The girls would take their seats and regard the phenomenon.

They were nice girls, ignorant as a rule, but nice. He knew some doctors who didn’t like trained nurses.

… Forty years ago, those doctors said, girls went into this because they had heard about Florence Nightingale and a life of service.

Many still did go in for it in that spirit, others simply went in for it. The best hospitals tried to weed these out. It took three years to be a nurse—in one more year you could be a doctor.

If a woman was serious why not take the whole thing? But then Bill thought:

“Poor kids. Half of them hadn’t any sort of education to start with, except what we give them…”

The flock of girls were in. With his notes and two books under his arm he followed.

“Sweet heaven!” he exclaimed, and decided to wait by the door till they quieted down. For a moment he looked over the parapet, over miles of morning, thinking again about himself.

Then, at the moment when he started to go into the classroom, the green skirt of a probationer blew out the door frantically.

“Dr. Craig—” she panted.

“What’s the excitement?”

“You ought to see what! It’s about the rabbit.”

“Now listen. Calm down. Now what?”

He couldn’t tell whether the girl was laughing or crying. His exasperation came to the fore—figuratively he took her by the shoulders and shook her.

“What nonsense! What on earth?”

He marched her into the classroom before him. An echolalia of idiotic laughter filled his ears—and he pushed his way through to the center of it crying: “What’s the matter?”

—and came upon Trouble. There she was in all her gorgeous beauty, standing beside the rabbit split for dissection, weeping wildly.

He couldn’t believe his eyes that it was she—because in spite of being God’s gift to men she had shown more promise than any other probationer.

—A girl suddenly fainted at his side and he pulled her up. Hysteria had swept the room and he saw that this girl had caused it by the sheer force of her personality—this girl who knocked him sidewise every time he saw her.

All in a split second he decided not to shout, but he spoke through gritted teeth.

“You bunch of quitters,” he said. “You bunch of quitters!”

He was losing control of himself and he knew it, but he went on.

“You’re trying to help people—and you’re scared of a dead rabbit. You—”

The girl, with all the beauty going out of her face, managed to throw her shoulders back and face him.

“I’m so sorry, doctor,” she sobbed. “But I kept rabbits when I was a girl and here’s this little bunny—split open—”

Then he said the word—a big word. It did not deny that they were females but it denied that they belonged to the race of homo sapiens, but rather a certain four-footed tribe.

Even as he heard it resound about him, the door opened and the superintendent of nurses came in.

He looked at her—all the temper rilled suddenly out of him.

“Good morning, Mrs. Caldwell.”

“Good morning, Doctor.” He saw in her face that she had heard, that she was shocked and amazed.

“All you students go out of here,” he said. “Wait on the terrace. Lecture’s postponed for a few minutes.”

There was a confused moment with the girls trying to apologize, and not knowing whom to