One Trip Abroad, F. Scott Fitzgerald

Published in The Saturday Evening Post magazine 11 October 1930

I

In the afternoon the air became black with locusts, and some of the women shrieked, sinking to the floor of the motorbus and covering their hair with traveling rugs.

The locusts were coming north, eating everything in their path, which was not so much in that part of the world; they were flying silently and in straight lines, flakes of black snow.

But none struck the windshield or tumbled into the car, and presently humorists began holding out their hands, trying to catch some. After ten minutes the cloud thinned out, passed, and the women emerged from the blankets, disheveled and feeling silly. And everyone talked together.

Everyone talked; it would have been absurd not to talk after having been through a swarm of locusts on the edge of the Sahara.

The Smyrna-American talked to the British widow going down to Biskra to have one last fling with an as-yet-unencountered sheik. The member of the San Francisco Stock Exchange talked shyly to the author. “Aren’t you an author?” he said.

The father and daughter from Wilmington talked to the cockney airman who was going to fly to Timbuctoo. Even the French chauffeur turned about and explained in a loud, clear voice: “Bumblebees,” which sent the trained nurse from New York into shriek after shriek of hysterical laughter.

Amongst the unsubtle rushing together of the travelers there was one interchange more carefully considered. Mr. and Mrs. Liddell Miles, turning as one person, smiled and spoke to the young American couple in the seat behind:

“Didn’t catch any in your hair?”

The young couple smiled back politely.

“No. We survived that plague.”

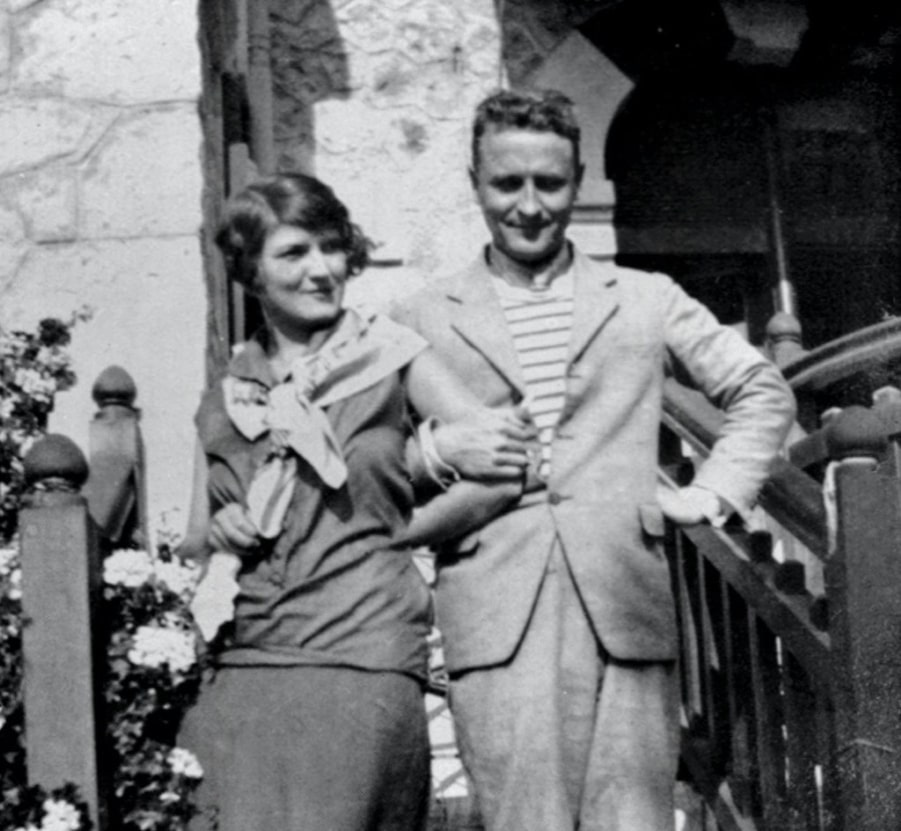

They were in their twenties, and there was still a pleasant touch of bride and groom upon them. A handsome couple; the man rather intense and sensitive, the girl arrestingly light of hue in eyes and hair, her face without shadows, its living freshness modulated by a lovely confident calm.

Mr. and Mrs. Miles did not fail to notice their air of good breeding, of a specifically “swell” background, expressed both by their unsophistication and by their ingrained reticence that was not stiffness.

If they held aloof, it was because they were sufficient to each other, while Mr. and Mrs. Miles’ aloofness toward the other passengers was a conscious mask, a social attitude, quite as public an affair in its essence as the ubiquitous advances of the Smyrna-American, who was snubbed by all.

The Mileses had, in fact, decided that the young couple were “possible” and, bored with themselves, were frankly approaching them.

“Have you been to Africa before? It’s been so utterly fascinating! Are you going on to Tunis?”

The Mileses, if somewhat worn away inside by fifteen years of a particular set in Paris, had undeniable style, even charm, and before the evening arrival at the little oasis town of Bou Saada they had all four become companionable.

They uncovered mutual friends in New York and, meeting for a cocktail in the bar of the Hotel Transatlantique, decided to have dinner together.

As the young Kellys came downstairs later, Nicole was conscious of a certain regret that they had accepted, realizing that now they were probably committed to seeing a certain amount of their new acquaintances as far as Constantine, where their routes diverged.

In the eight months of their marriage she had been so very happy that it seemed like spoiling something.

On the Italian liner that had brought them to Gibraltar they had not joined the groups that leaned desperately on one another in the bar; instead, they seriously studied French, and Nelson worked on business contingent on his recent inheritance of half a million dollars.

Also he painted a picture of a smokestack. When one member of the gay crowd in the bar disappeared permanently into the Atlantic just this side of the Azores, the young Kellys were almost glad, for it justified their aloof attitude.

But there was another reason Nicole was sorry they had committed themselves. She spoke to Nelson about it: “I passed that couple in the hall just now.”

“Who–the Mileses?”

“No, that young couple–about our age–the ones that were on the other motorbus, that we thought looked so nice, in Bir Rabalou after lunch, in the camel market.”

“They did look nice.”

“Charming,” she said emphatically; “the girl and man, both. I’m almost sure I’ve met the girl somewhere before.”

The couple referred to were sitting across the room at dinner, and Nicole found her eyes drawn irresistibly toward them. They, too, now had companions, and again Nicole, who had not talked to a girl of her own age for two months, felt a faint regret.

The Mileses, being formally sophisticated and frankly snobbish, were a different matter. They had been to an alarming number of places and seemed to know all the flashing phantoms of the newspapers.

They dined on the hotel veranda under a sky that was low and full of the presence of a strange and watchful God; around the corners of the hotel the night already stirred with the sounds of which they had so often read but that were even so hysterically unfamiliar–drums from Senegal, a native flute, the selfish, effeminate whine of a camel, the Arabs pattering past in shoes made of old automobile tires, the wail of Magian prayer.

At the desk in the hotel, a fellow passenger was arguing monotonously with the clerk about the rate of exchange, and the inappropriateness added to the detachment which had increased steadily as they went south.

Mrs. Miles was the first to break the lingering silence; with a sort of impatience she pulled them with her, in from the night and up to the table.

“We really should have dressed. Dinner’s more amusing if people dress, because they feel differently in formal clothes. The English know that.”

“Dress here?” her husband objected. “I’d feel like that man in the ragged dress suit we passed today, driving the flock of sheep.”

“I always feel like a tourist if I’m not dressed.”

“Well, we are, aren’t we?” asked Nelson.

“I don’t consider myself a tourist. A tourist is somebody who gets up early and goes to cathedrals and talks about scenery.”

Nicole and Nelson, having seen all the official sights from Fez to Algiers, and taken reels of moving pictures and felt improved, confessed themselves, but decided that their experiences on the trip would not interest Mrs. Miles.

“Every place is the same,” Mrs. Miles continued. “The only thing that matters is who’s there. New scenery is fine for half an hour, but after that you want your own kind to see. That’s why some places have a certain vogue, and then the vogue changes and the people move on somewhere else. The place itself really never matters.”

“But doesn’t somebody first decide that the place is nice?” objected Nelson. “The first ones go there because they like the place.”

“Where were you going this spring?” Mrs. Miles asked.

“We thought of San Remo, or maybe Sorrento. We’ve never been to Europe before.”

“My children, I know both Sorrento and San Remo, and you won’t stand either of them for a week. They’re full of the most awful English, reading the Daily Mail and waiting for letters and talking about the most incredibly dull things.

You might as well go to Brighton or Bournemouth and buy a white poodle and a sunshade and walk on the pier. How long are you staying in Europe?”

“We don’t know; perhaps several years.” Nicole hesitated. “Nelson came into a little money, and we wanted a change.

When I was young, my father had asthma and I had to live in the most depressing health resorts with him for years; and Nelson was in the fur business in Alaska and he loathed it; so when we were free we came abroad. Nelson’s going to paint and I’m going to study singing.” She looked triumphantly at her husband. “So far, it’s been absolutely gorgeous.”

Mrs. Miles decided, from the evidence of the younger woman’s clothes, that it was quite a bit of money, and their enthusiasm was infectious.

“You really must go to Biarritz,” she advised them. “Or else come to Monte Carlo.”

“They tell me there’s a great show here,” said Miles, ordering champagne. “The Ouled Naïls. The concierge says they’re some kind of tribe of girls who come down from the mountains and learn to be dancers, and what not, till they’ve collected enough gold to go back to their mountains and marry. Well, they give a performance tonight.”

Walking over to the Café of the Ouled Naïls afterward, Nicole regretted that she and Nelson were not strolling alone through the ever-lower, ever-softer, ever-brighter night.

Nelson had reciprocated the bottle of champagne at dinner, and neither of them was accustomed to so much.

As they drew near the sad flute she didn’t want to go inside, but rather to climb to the top of a low hill where a white mosque shone clear as a planet through the night. Life was better than any show; closing in toward Nelson, she pressed his hand.

The little cave of a café was filled with the passengers from the two busses. The girls–light-brown, flat-nosed Berbers with fine, deep-shaded eyes–were already doing each one her solo on the platform.

They wore cotton dresses, faintly reminiscent of Southern mammies; under these their bodies writhed in a slow nautch, culminating in a stomach dance, with silver belts bobbing wildly and their strings of real gold coins tinkling on their necks and arms.

The flute player was also a comedian; he danced, burlesquing the girls. The drummer, swathed in goatskins like a witch doctor,