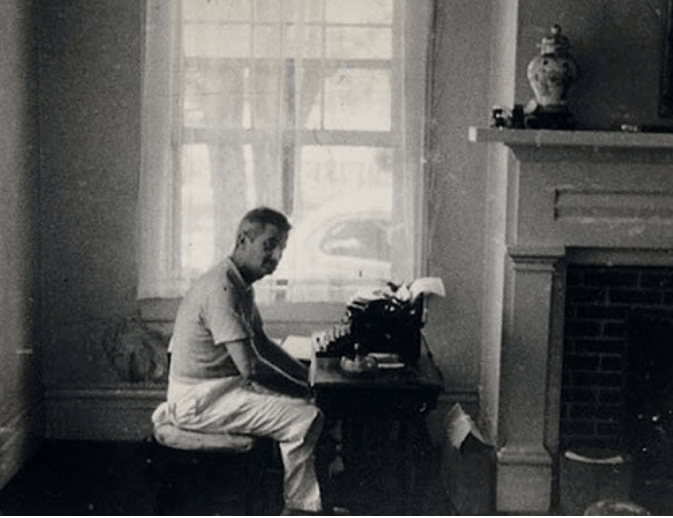

Artist at Home, William Faulkner

Artist at Home

ROGER HOWES WAS a fattish, mild, nondescript man of forty, who came to New York from the Mississippi Valley somewhere as an advertisement writer and married and turned novelist and sold a book and bought a house in the Valley of Virginia and never went back to New York again, even on a visit.

For five years he had lived in the old brick house with his wife Anne and their two children, where old ladies came to tea in horsedrawn carriages or sent the empty carriages for him or sent by Negro servants in the otherwise empty carriages shoots and cuttings of flowering shrubs and jars of pickle or preserves and copies of his books for autographs.

He didn’t go back to New York any more, but now and then New York came to visit him: the ones he used to know, the artists and poets and such he knew before he began to earn enough food to need a cupboard to put it in.

The painters, the writers, that hadn’t sold a book or a picture — men with beards sometimes in place of collars, who came and wore his shirts and socks and left them under the bureau when they departed, and women in smocks but sometimes not: those gaunt and eager and carnivorous tymbesteres of Art.

At first it had been just hard to refuse them, but now it was harder to tell his wife that they were coming. Sometimes he did not know himself they were coming. They usually wired him, on the day on which they would arrive, usually collect.

He lived four miles from the village and the book hadn’t sold quite enough to own a car too, and he was a little fat, a little overweight, so sometimes it would be two or three days before he would get his mail. Maybe he would just wait for the next batch of company to bring the mail up with them.

After the first year the man at the station (he was the telegraph agent and the station agent and Roger’s kind of town agent all in one) got to where he could recognize them on sight.

They would be standing on the little platform, with that blank air, with nothing to look at except a little yellow station and the back end of a moving train and some mountains already beginning to get dark, and the agent would come out of his little den with a handful of mail and a package or so, and the telegram. “He lives about four miles up the Valley. You can’t miss it.”

“Who lives about four miles up the valley?”

“Howes does. If you all are going up there, I thought maybe you wouldn’t mind taking these letters to him. One of them is a telegram.”

“A telegram?”

“It come this a.m. But he ain’t been to town in two-three days. I thought maybe you’d take it to him.”

“Telegram? Hell. Give it here.”

“It’s forty-eight cents to pay on it.”

“Keep it, then. Hell.”

So they would take everything except the telegram and they would walk the four miles to Howes’, getting there after supper. Which would be all right, because the women would all be too mad to eat anyway, including Mrs. Howes, Anne. So a couple of days later, someone would send a carriage for Roger and he would stop at the village and pay out the wire telling him how his guests would arrive two days ago.

So when this poet in the sky-blue coat gets off the train, the agent comes right out of his little den, with the telegram. “It’s about four miles up the Valley,” he says. “You can’t miss it. I thought maybe you’d take this telegram up to him. It come this a.m., but he ain’t been to town for two-three days. You can take it. It’s paid.”

“I know it is,” the poet says. “Hell. You say it is four miles up there?”

“Right straight up the road. You can’t miss it.”

So the poet took the telegram and the agent watched him go on out of sight up the Valley Road, with a couple or three other folks coming to the doors to look at the blue coat maybe. The agent grunted. “Four miles,” he said. “That don’t mean no more to that fellow than if I had said four switch frogs.

But maybe with that dressing-sacque he can turn bird and fly it.”

Roger hadn’t told his wife, Anne, about this poet at all, maybe because he didn’t know himself. Anyway, she didn’t know anything about it until the poet came limping into the garden where she was cutting flowers for the supper table, and told her she owed him forty-eight cents.

“Forty-eight cents?” Anne said.

He gave her the telegram. “You don’t have to open it now, you see,” the poet said. “You can just pay me back the forty-eight cents and you won’t have to even open it.” She stared at him, with a handful of flowers and the scissors in the other hand, so finally maybe it occurred to him to tell her who he was. “I’m John Blair,” he said. “I sent this telegram this morning to tell you I was coming. It cost me forty-eight cents. But now I’m here, so you don’t need the telegram.”

So Anne stands there, holding the flowers and the scissors, saying “Damn, Damn, Damn” while the poet tells her how she ought to get her mail oftener. “You want to keep up with what’s going on,” he tells her, and her saying “Damn, Damn, Damn,” until at last he says he’ll just stay to supper and then walk back to the village, if it’s going to put her out that much.

“Walk?” she said, looking him up and down. “You walk? Up here from the village? I don’t believe it. Where is your baggage?”

“I’ve got it on. Two shirts, and I have an extra pair of socks in my pocket. Your cook can wash, can’t she?”

She looks at him, holding the flowers and the scissors. Then she tells him to come on into the house and live there forever. Except she didn’t say exactly that. She said: “You walk? Nonsense. I think you’re sick. You come in and sit down and rest.” Then she went to find Roger and tell him to bring down the pram from the attic. Of course she didn’t say exactly that, either.

Roger hadn’t told her about this poet; he hadn’t got the telegram himself yet. Maybe that was why she hauled him over the coals so that night: because he hadn’t got the telegram.

They were in their bedroom. Anne was combing out her hair. The children were spending the summer up in Connecticut, with Anne’s folks. He was a minister, her father was.

“You told me that the last time would be the last. Not a month ago. Less than that, because when that last batch left I had to paint the furniture in the guest room again to hide where they put their cigarettes on the dressing table and the window ledges.

And I found in a drawer a broken comb I would not have asked Pinkie (Pinkie was the Negro cook) to pick up, and two socks that were not even mates that I bought for you myself last winter, and a single stocking that I couldn’t even recognize any more as mine. You tell me that Poverty looks after its own: well, let it. But why must we be instruments of Poverty?”

“This is a poet. That last batch were not poets. We haven’t had a poet in the house in some time. Place losing all its mellifluous overtones and subtleties.”

“How about that woman that wouldn’t bathe in the bathroom? who insisted on going down to the creek every morning without even a bathing suit, until Amos Crain’s (he was a farmer that lived across the creek from them) wife had to send me word that Amos was afraid to try to plow his lower field? What do people like that think that out-doors, the country, is? I cannot understand it, any more than I can understand why you feel that you should feed and lodge—”

“Ah, that was just a touch of panic fear that probably did Amos good. Jolted him out of himself, out of his rut.”

“The rut where he made his wife’s and children’s daily bread, for six days. And worse than that. Amos is young. He probably had illusions about women until he saw that creature down there without a stitch on.”

“Well, you are in the majority, you and Mrs. Crain.” He looked at the back of her head, her hands combing out her hair, and her probably watching him in the mirror and him not knowing it, what with being an artist and all. “This is a man poet.”

“Then I suppose he will refuse to leave the bathroom at all. I suppose you’ll have to carry a tray to him in the tub three times a day. Why do you feel compelled to lodge and feed these people? Can’t you see they consider you an easy mark? that they eat your food and wear your clothes and consider us hopelessly bourgeois for having enough food for other people to eat, and a little soft-brained for giving it away? And now this one, in a sky-blue dressing-sacque.”

“There’s a lot of wear and tear to just being a poet. I don’t think you realize that.”

“Oh, I don’t mind. Let him wear a lamp shade or a sauce pan too. What does he want of you? advice, or just food