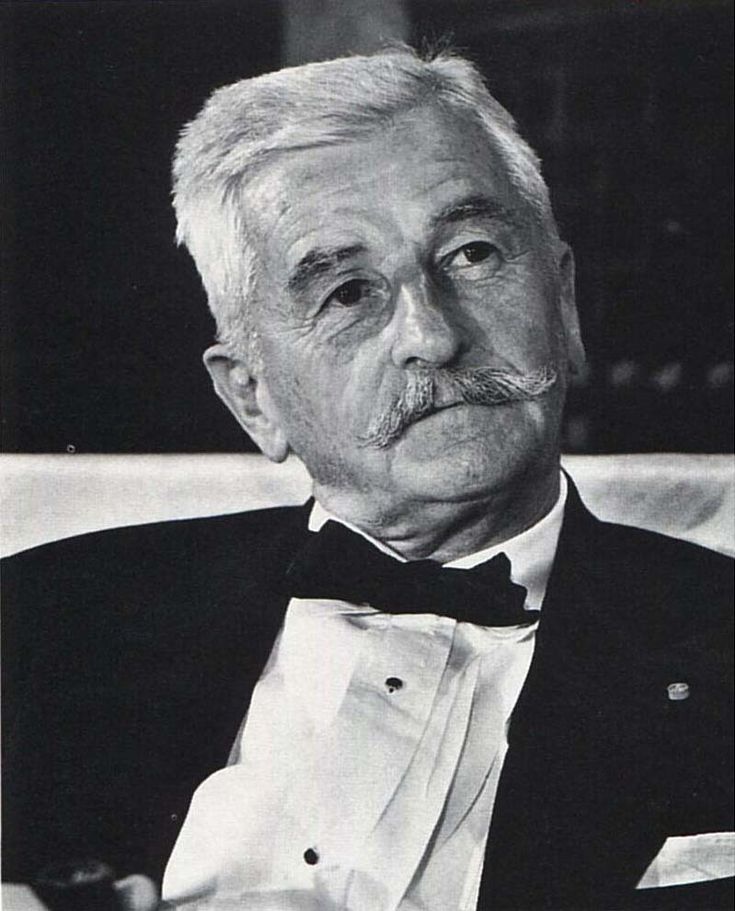

Dr. Martino, William Faulkner

Dr. Martino

HUBERT JARROD MET Louise King at a Christmas house party in Saint Louis. He had stopped there on his way home to Oklahoma to oblige, with his aura of oil wells and Yale, the sister of a classmate. Or so he told himself, or so he perhaps believed.

He had planned to stop off at Saint Louis two days and he stayed out the full week, going on to Tulsa overnight to spend Christmas Day with his mother and then returning, “to play around a little more with my swamp angel,” he told himself.

He thought about her quite a lot on the return train — a thin, tense, dark girl. “That to come out of Mississippi,” he thought. “Because she’s got it: a kid born and bred in a Mississippi swamp.”

He did not mean sex appeal. He could not have been fooled by that alone, who had been three years now at New Haven, belonging to the right clubs and all and with money to spend. And besides, Louise was a little on the epicene.

What he meant was a quality of which he was not yet consciously aware: a beyond-looking, a passionate sense for and belief in immanent change to which the rhinoceroslike sufficiency of his Yale and oil-well veneer was a little impervious at first. All he remarked at first was the expectation, the seeking, which he immediately took to himself.

Apparently he was not wrong. He saw her first across the dinner-table. They had not yet been introduced, yet ten minutes after they left the table she had spoken to him, and ten minutes after that they had slipped out of the house and were in a taxi, and she had supplied the address.

He could not have told himself how it happened, for all his practice, his experience in surreptitiousness. Perhaps he was too busy looking at her; perhaps he was just beginning to be aware that the beyond-looking, the tense expectation, was also beyond him — his youth, his looks, the oil wells and Yale. Because the address she had given was not toward any lights or music apparently, and she sitting beside him, furred and shapeless, her breath vaporizing faster than if she had been trying to bring to life a dead cigarette. He watched the dark houses, the dark, mean streets. “Where are we going?” he said.

She didn’t answer, didn’t look at him, sitting a little forward on the seat. “Mamma didn’t want to come,” she said.

“Your mother?”

“She’s with me. Back there at the party. You haven’t met her yet.”

“Oh. So that’s what you are slipping away from. I flattered myself. I thought I was the reason.” She was sitting forward, small, tense, watching the dark houses: a district half dwellings and half small shops. “Your mother won’t let him come to call on you?”

She didn’t answer, but leaned forward. Suddenly she tapped on the glass. “Here, driver!” she said. “Right here.” The cab stopped. She turned to face Jarrod, who sat back in his corner, muffled, his face cold. “I’m sorry. I know it’s a rotten trick. But I had to.”

“Not at all,” Jarrod said. “Don’t mention it.”

“I know it’s rotten. But I just had to. If you just understood.”

“Sure,” Jarrod said. “Do you want me to come back and get you? I’d better not go back to the party alone.”

“You come in with me.”

“Come in?”

“Yes. It’ll be all right. I know you can’t understand. But it’ll be all right. You come in too.”

He looked at her face. “I believe you really mean it,” he said. “I guess not. But I won’t let you down. You set a time, and I’ll come back.”

“Don’t you trust me?”

“Why should I? It’s no business of mine. I never saw you before to-night. I’m glad to oblige you. Too bad I am leaving to-morrow. But I guess you can find somebody else to use. You go on in; I’ll come back for you.”

He left her there and returned in two hours. She must have been waiting just inside the door, because the cab had hardly stopped before the door opened and she ran down the steps and sprang into the cab before he could dismount. “Thank you,” she said. “Thank you. You were kind. You were so kind.”

When the cab stopped beneath the porte-cochère of the house from which music now came, neither of them moved at once. Neither of them made the first move at all, yet a moment later they kissed. Her mouth was still, cold. “I like you,” she said. “I do like you.”

Before the week was out Jarrod offered to serve her again so, but she refused, quietly. “Why?” he said. “Don’t you want to see him again?” But she wouldn’t say, and he had met Mrs. King by that time and he said to himself, “The old girl is after me, anyway.”

He saw that at once; he took that also as the meed due his oil wells and his Yale nimbus, since three years at New Haven, leading no classes and winning no football games, had done nothing to dispossess him of the belief that he was the natural prey of all mothers of daughters.

But he didn’t flee, not even after he found, a few evenings later, Louise again unaccountably absent, and knew that she had gone, using someone else for the stalking horse, to that quiet house in the dingy street. “Well, I’m done,” he said to himself. “I’m through now.” But still he didn’t flee, perhaps because she had used someone else this time. “She cares that much, anyway,” he said to himself.

When he returned to New Haven he had Louise’s promise to come to the spring prom. He knew now that Mrs. King would come too. He didn’t mind that; one day he suddenly realized that he was glad.

Then he knew that it was because he too knew, believed, that Louise needed looking after; that he had already surrendered unconditionally to one woman of them, he who had never once mentioned love to himself, to any woman. He remembered that quality of beyond-looking and that dark, dingy house in Saint Louis, and he thought, “Well, we have her.

We have the old woman.” And one day he believed that he had found the reason if not the answer. It was in class, in psychology, and he found himself sitting bolt upright, looking at the instructor. The instructor was talking about women, about young girls in particular, about that strange, mysterious phase in which they live for a while.

“A blind spot, like that which racing aviators enter when making a fast turn. When what they see is neither good nor evil, and so what they do is likely to be either one. Probably more likely to be evil, since the very evilness of evil stems from its own fact, while good is an absence of fact. A time, an hour, in which they themselves are victims of that by means of which they victimize.”

That night he sat before his fire for some time, not studying, not doing anything. “We’ve got to be married soon,” he said. “Soon.”

Mrs. King and Louise arrived for the prom. Mrs. King was a gray woman, with a cold, severe face, not harsh, but watchful, alert. It was as though Jarrod saw Louise, too, for the first time. Until then he had not been aware that he was conscious of the beyond-looking quality. It was only now that he saw it by realizing how it had become tenser, as though it were now both dread and desire; as though with the approach of summer she were approaching a climax, a crisis. So he thought that she was ill.

“Maybe we ought to be married right away,” he said to Mrs. King. “I don’t want a degree, anyway.” They were allies now, not yet antagonists, though he had not told her of the two Saint Louis expeditions, the one he knew of and the one he suspected. It was as though he did not need to tell her. It was as though he knew that she knew; that she knew he knew she knew.

“Yes,” she said. “At once.”

But that was as far as it got, though when Louise and Mrs. King left New Haven, Louise had his ring. But it was not on her hand, and on her face was that strained, secret, beyond-looking expression which he now knew was beyond him too, and the effigy and shape which the oil wells and Yale had made. “Till July, then,” he said.

“Yes,” she said. “I’ll write. I’ll write you when to come.”

And that was all. He went back to his clubs, his classes; in psychology especially he listened. “It seems I’m going to need psychology,” he thought, thinking of the dark, small house in Saint Louis, the blank, dark door through which, running, she had disappeared. That was it: a man he had never seen, never heard of, shut up in a little dingy house on a back street on Christmas eve. He thought, fretfully, “And me young, with money, a Yale man. And I don’t even know his name.”

Once a week he wrote to Louise; perhaps twice a month he received replies — brief, cold notes mailed always at a different place — resorts and hotels — until mid-June, within a week of Commencement and his degree. Then he received a wire. It was from Mrs. King.

It said Come at once and the location was Cranston’s Wells, Mississippi. It was a town he had never heard of.

That was Friday; thirty