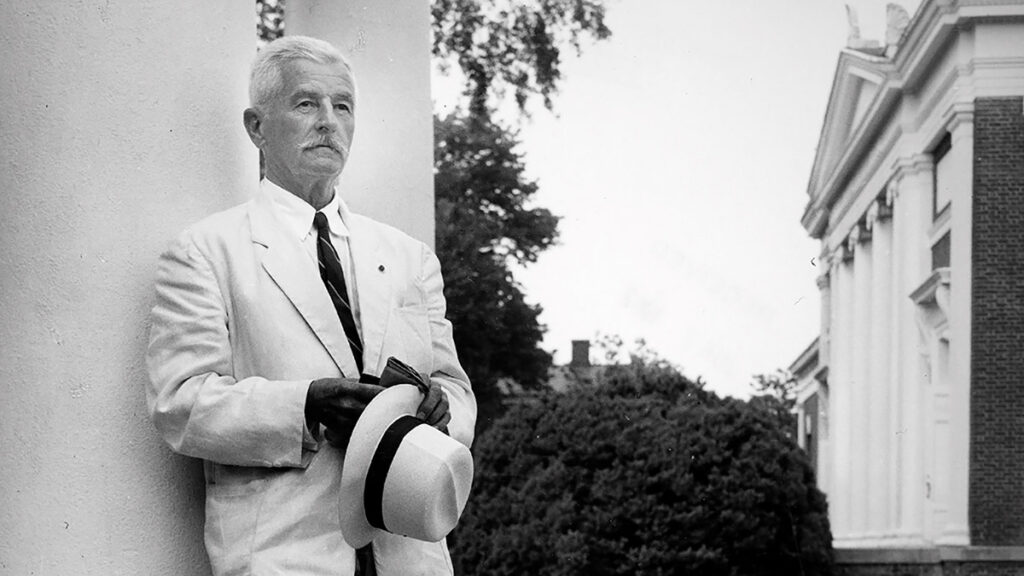

Hand Upon the Waters, William Faulkner

Hand Upon the Waters

I

THE TWO MEN followed the path where it ran between the river and the dense wall of cypress and cane and gum and brier. One of them carried a gunny sack which had been washed and looked as if it had been ironed too. The other was a youth, less than twenty, by his face. The river was low, at mid-July level.

‘He ought to been catching fish in this water,’ the youth said.

‘If he happened to feel like fishing,’ the one with the sack said. ‘Him and Joe run that line when Lonnie feels like it, not when the fish are biting.’

‘They’ll be on the line, anyway,’ the youth said. ‘I don’t reckon Lonnie cares who takes them off for him.’

Presently the ground rose to a cleared point almost like a headland. Upon it sat a conical hut with a pointed roof, built partly of mildewed canvas and odd-shaped boards and partly of oil tins hammered out flat. A rusted stovepipe projected crazily above it, there was a meager woodpile and an ax, and a bunch of cane poles leaned against it. Then they saw, on the earth before the open door, a dozen or so short lengths of cord just cut from a spool near by, and a rusted can half full of heavy fishhooks, some of which had already been bent onto the cords. But there was nobody there.

‘The boat’s gone,’ the man with the sack said. ‘So he ain’t gone to the store.’ Then he discovered that the youth had gone on, and he drew in his breath and was just about to shout when suddenly a man rushed out of the undergrowth and stopped, facing him and making an urgent whimpering sound — a man not large, but with tremendous arms and shoulders; an adult, yet with something childlike about him, about the way he moved, barefoot, in battered overalls and with the urgent eyes of the deaf and dumb.

‘Hi, Joe,’ the man with the sack said, raising his voice as people will with those who they know cannot understand them. ‘Where’s Lonnie?’ He held up the sack. ‘Got some fish?’

But the other only stared at him, making that rapid whimpering. Then he turned and scuttled on up the path where the youth had disappeared, who, at that moment, shouted: ‘Just look at this line!’

The older one followed. The youth was leaning eagerly out over the water beside a tree from which a light cotton rope slanted tautly downward into the water. The deaf-and-dumb man stood just behind him, still whimpering and lifting his feet rapidly in turn, though before the older man reached him he turned and scuttled back past him, toward the hut. At this stage of the river the line should have been clear of the water, stretching from bank to bank, between the two trees, with only the hooks on the dependent cords submerged. But now it slanted into the water from either end, with a heavy downstream sag, and even the older man could feel movement on it. ‘It’s big as a man!’ the youth cried.

‘Yonder’s his boat,’ the older man said. The youth saw it, too — across the stream and below them, floated into a willow clump inside a point. ‘Cross and get it, and we’ll see how big this fish is.’

The youth stepped out of his shoes and overalls and removed his shirt and waded out and began to swim, holding straight across to let the current carry him down to the skiff, and got the skiff and paddled back, standing erect in it and staring eagerly upstream toward the heavy sag of the line, near the center of which the water, from time to time, roiled heavily with submerged movement. He brought the skiff in below the older man, who, at that moment, discovered the deaf-and-dumb man just behind him again, still making the rapid and urgent sound and trying to enter the skiff.

‘Get back!’ the older man said, pushing the other back with his arm. ‘Get back, Joe!’

‘Hurry up!’ the youth said, staring eagerly toward the submerged line, where, as he watched, something rolled sluggishly to the surface, then sank again. ‘There’s something on there, or there ain’t a hog in Georgia. It’s big as a man too!’

The older one stepped into the skiff. He still held the rope, and he drew the skiff, hand over hand, along the line itself.

Suddenly, from the bank of the river behind them, the deaf-and-dumb man began to make an actual sound. It was quite loud.

II

‘Inquest?’ Stevens said.

‘Lonnie Grinnup.’ The coroner was an old country doctor. ‘Two fellows found him drowned on his own trotline this morning.’

‘No!’ Stevens said. ‘Poor damned feeb. I’ll come out.’ As county attorney he had no business there, even if it had not been an accident. He knew it. He was going to look at the dead man’s face for a sentimental reason.

What was now Yoknapatawpha County bad been founded not by one pioneer but by three simultaneous ones. They came together on horseback, through the Cumberland Gap from the Carolinas, when Jefferson was still a Chickasaw Agency post, and bought land in the Indian patent and established families and flourished and vanished, so that now, a hundred years afterward, there was in all the county they helped to found but one representative of the three names.

This was Stevens, because the last of the Holston family had died before the end of the last century, and the Louis Grenier, whose dead face Stevens was driving eight miles in the heat of a July afternoon to look at, had never even known he was Louis Grenier.

He could not even spell the Lonnie Grinnup he called himself — an orphan, too, like Stevens, a man a little under medium size and somewhere in his middle thirties, whom the whole county knew — the face which was almost delicate when you looked at it again, equable, constant, always cheerful, with an invariable fuzz of soft golden beard which had never known a razor, and light-colored peaceful eyes— ‘touched,’ they said, but whatever it was, bad touched him lightly, taking not very much away that need be missed — living, year in and year out, in the hovel he had built himself of an old tent and a few mismatched boards and flattened oil tins, with the deaf-and-dumb orphan he had taken into his hut ten years ago and clothed and fed and raised, and who had not even grown mentally as far as he himself had.

Actually his hut and trotline and fish trap were in almost the exact center of the thousand and more acres his ancestors had once owned. But he never knew it.

Stevens believed he would not have cared, would have declined to accept the idea that any one man could or should own that much of the earth which belongs to all, to every man for his use and pleasure — in his own case, that thirty or forty square feet where his hut sat and the span of river across which his trotline stretched, where anyone was welcome at any time, whether he was there or not, to use his gear and eat his food as long as there was food.

And at times he would wedge his door shut against prowling animals and with his deaf-and-dumb companion he would appear without warning or invitation at houses or cabins ten and fifteen miles away, where he would remain for weeks, pleasant, equable, demanding nothing and without servility, sleeping wherever it was convenient for his hosts to have him sleep — in the hay of lofts, or in beds in family or company rooms, while the deaf-and-dumb youth lay on the porch or the ground just outside, where he could hear him who was brother and father both, breathing. It was his one sound out of all the voiceless earth. He was infallibly aware of it.

It was early afternoon. The distances were blue with heat. Then, across the long flat where the highway began to parallel the river bottom, Stevens saw the store. By ordinary it would have been deserted, but now he could already see clotted about it the topless and battered cars, the saddled horses and mules and the wagons, the riders and drivers of which he knew by name. Better still, they knew him, voting for him year after year and calling him by his given name even though they did not quite understand him, just as they did not understand the Harvard Phi Beta Kappa key on his watch chain. He drew in beside the coroner’s car.

Apparently it was not to be in the store, but in the grist mill beside it, before the open door of which the clean Saturday overalls and shirts and the bared heads and the sunburned necks striped with the white razor lines of Saturday neck shaves were densest and quietest. They made way for him to enter. There was a table and three chairs where the coroner and two witnesses sat.

Stevens noticed a man of about forty holding a clean gunny sack, folded and refolded until it resembled a book, and a youth whose face wore an expression of weary yet indomitable amazement.

The body lay under a quilt on the low platform to which the silent mill was bolted. He crossed to it and raised the corner of the quilt and looked at the face and lowered the quilt and turned, already on his way back to town, and then he did