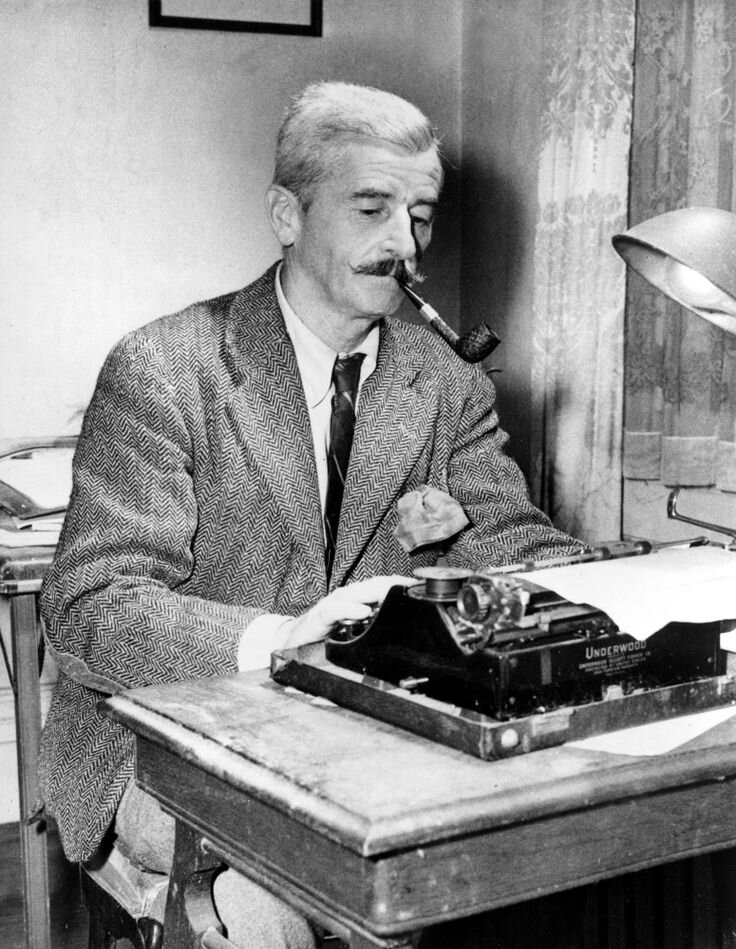

Idyll in the Desert, William Faulkner

Idyll in the Desert

Random House, December 1931

I

“It would take me four days to make my route. I would leave Blizzard on a Monday and get to Painter’s about sundown and spend the night. The next night I would make Ten Sleep and then turn and go back across the mesa. The third night I would camp, and on Thursday night I would be home again.”

“Didn’t you ever get lonesome?” I said.

“Well, a fellow hauling government mail, government property. You hear tell of these old desert rats getting cracked in the head. But did you ever hear of a soldier getting that way? Even a West Pointer, a fellow out of the cities, that never was out of hollering distance of a hundred people before in his life, let him be out on a scout by himself for six months, even.

Because that West Pointer, he’s like me; he ain’t riding alone. He’s got Uncle Sam right there to talk to whenever he feels like talking: Washington and the big cities full of folks, and all that that means to a man, like what Saint Peter and the Holy Church of Rome used to mean to them old priests, when them Spanish Bishops would come riding across the mesa on a mule, surrounded by the ghostly hosts of Heaven with harder hitting guns than them old Sharpses even, because the pore aboriginee that got shot with them heavenly bolts, they never even saw the shooting, let alone the gun. And then I carry a rifle, and there’s always the chance of an antelope and once I killed a mountain sheep without even getting out of the buckboard.”

“Was it a big one?” I said.

“Sure. I was coming around a shoulder of the canyon just about sunset. The sun was just above the rim, shining right in my face. So I saw these two sheep just under the rim. I could see their horns and tails against the sky, but I couldn’t see the sheep for the sunset.

I could see a set of horns, I could make out a pair of hindquarters, but because of the sun I couldn’t make out if them sheep were on this side of the rim or just beyond it. And I didn’t have time to get closer. I just pulled the team up and throwed up my rifle and put a bullet about two foot back of them horns and another bullet about three foot ahead of them hindquarters and jumped out of the blackboard running.”

“Did you get both of them?” I said.

“No. I just got one. But he had two bullets in him; one back of the fore leg and the other right under the hind leg.”

“Oh,” I said.

“Yes. Them bullets was five foot apart.”

“That’s a good story,” I said.

“It was a good sheep. But what was I talking about? I talk so little that, when I mislay a subject, I have to stop and hunt for it. I was talking about being lonesome, wasn’t I? There wouldn’t hardly a winter pass without I would have at least one passenger on the up or down trip, even if it wasn’t anybody but one of Painter’s hands, done rode his horse down to Blizzard with forty dollars in his pocket, to leave his horse at Blizzard and go down to Juarez and bust the bank with that forty dollars by Christmas day and come back and maybe set up with Painter for his range boss, provided if Painter was honest and industrious and worked hard. They’d always ride back up to Painter’s with me along about New Year’s.”

“What about their horses?” I said.

“What horses?”

“The ones they rode down to Blizzard and left there.”

“Oh. Them horses would belong to Matt Lewis by that time. Matt runs the livery stable.”

“Oh,” I said.

“Yes. Matt says he don’t know what to do. He said he kept on hoping that maybe this polo would take the country like Mah-Jong done a while back. But now he says he reckons he’ll have to start him a glue factory. But what was I talking about?”

“You talk so seldom,” I said. “Was it about getting lonesome?”

“Oh yes. And then I’d have these lungers. That would be a passenger a week for two weeks.”

“Would they come in pairs?”

“No. It would be the same one. I’d take him up one week and leave him, and the next week I’d bring him back down to make the east bound train. I reckon the air up at Sivgut was a little too stiff for eastern lungs.”

“Sivgut?” I said.

“Sure. Siv. One of them things they strain the meal through back east at Santone and Washinton. Siv.”

“Oh. Siv. Yes. Sivgut. What is that?”

“It’s a house we built. A good house. They kept on coming here, getting off at Blizzard, passing Phoenix where there is what you might call back east at Santone and Washinton a dude lung-ranch. They’d pass that and come on to Blizzard: a peaked-looking fellow in his Sunday clothes, with his eyes closed and his skin the color of sandpaper, and a fat wife from one of them eastern corn counties, telling how they wanted too much at Phoenix so they come on to Blizzard because they don’t think a set of eastern wore-out lungs is worth what the folks in Phoenix wanted.

Or maybe it would be vice versa, with the wife with a sand-colored face with a couple of red spots on it like the children had been spending a wet Sunday with some scraps of red paper and a pot of glue while she was asleep, and her still asleep but not too much asleep to put in her opinion about how much folks in Phoenix thought Ioway lungs was worth on the hoof. So we built Sivgut for them. The Blizzard Chamber of Commerce did it, with two bunks and a week’s grub, because it takes me a week to get up there again and bring them back down to make the Phoenix train. It’s a good camp. We named it Sivgut because of the view.

On a clear day you can see clean down into Mexico. Did I tell you about the day when that last revolution broke out in Mexico? Well, one day — it was a Tuesday, about ten o’clock in the morning — I got there and the lunger was out in front, staring off to the south with his hand shading his eyes. ‘It’s a cloud of dust,’ he says. ‘Look at it.’ I looked. ‘That’s curious,’ I said. ‘It can’t be a rodeo or I’d heard about it. And it can’t be a sandstorm,’ I said, ‘because it’s too big and staying in one place.’ I went on and got back to Blizzard on Thursday. Then I learned about this new revolution down in Mexico. Broke out Tuesday just before sundown, they told me.”

“I thought you said you saw that dust at ten o’clock,” I said.

“Sure. But things happen so fast down there in Mexico that that dust started rising the night before to get out of the way of—”

“Don’t tell about that,” I said. “Tell about Sivgut.”

“All right. I’d get up to Sivgut on Tuesday morning. At first she’d be in the door, or maybe out in front of the cabin, looking down the trail for me. But after that sometimes I would drive right up to the door and stop the team and say ‘Hello’ and the house still as vacant as the day it was built.”

“A woman,” I said.

“Yes. She stayed on, after he got well and left. She stayed on.”

“She must have liked the country.”

“I guess not. I don’t guess any of them liked the country. Would you like a country you were just using to get well from a sickness you were ashamed for your friends to know you had?”

“I see.” I said. “He got well first. Why didn’t he wait until his wife got well too?”

“I guess he never had time to wait. I guess he figgered there was a right smart lot for him to do yet back yonder, being a young fellow, and like he had just got out of jail after a long time.”

“That’s less reason than ever for him to leave his wife sick.”

“He didn’t know she was sick. That she had it too.”

“Didn’t know?” I said.

“You take a sick fellow, a young fellow at that, without no ties to speak of, having to come and live for two years in a place where there ain’t a traffic light in four hundred miles; where there ain’t nothing but quiet and sunlight and them durn stars staring him in the face all night long. You couldn’t expect him to pay much mind to somebody that never done nothing but cook his food and chop his firewood and haul his water in a tin bucket from a spring three quarters of a mile away to wash him in like he was a baby. So when he got well, I don’t reckon he could be blamed for not noticing that she had one more burden herself, especially if that burden wasn’t nothing but a few little old bugs.”

“I don’t know what you call ties, then,” I said, “If marriage isn’t a tie.”

“Now you’re getting at it. Marriage is a tie; only, it depends some on who you are married to. You know what my private opinion is, after having watched them for about ten years, once a week on a Tuesday, as well as carrying a letter or a telegram back