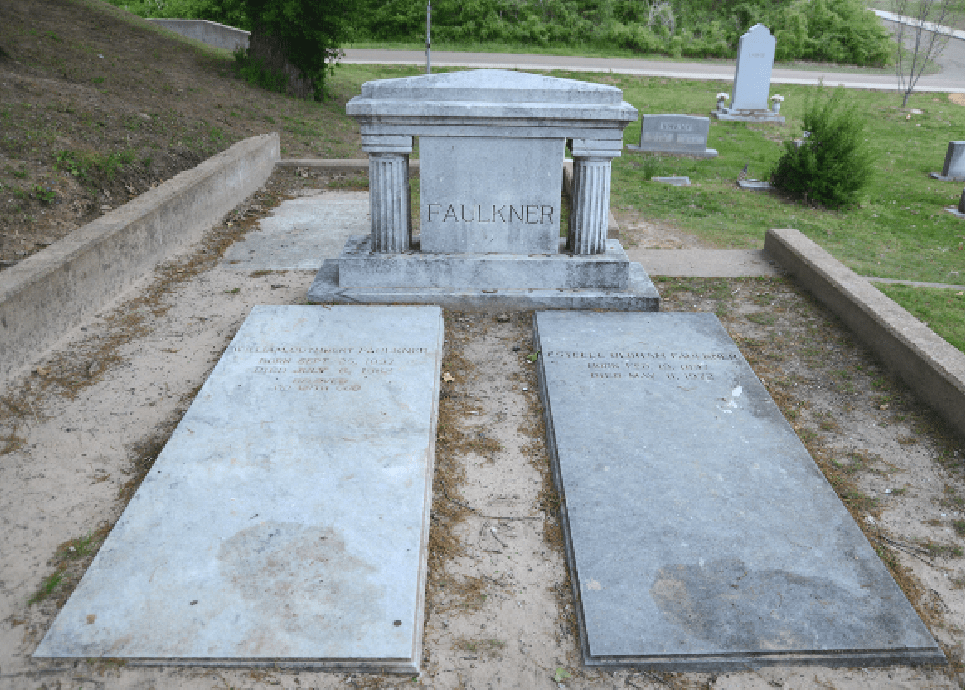

Lo! William Faulkner

Lo!

THE PRESIDENT STOOD motionless at the door of the Dressing Room, fully dressed save for his boots. It was half-past six in the morning and it was snowing; already he had stood for an hour at the window, watching the snow.

Now he stood just inside the door to the corridor, utterly motionless in his stockings, stooped a little from his lean height as though listening, on his face an expression of humorless concern, since humor had departed from his situation and his view of it almost three weeks before. Hanging from his hand, low against his flank, was a hand mirror of elegant French design, such as should have been lying upon a lady’s dressing table: certainly at this hour of a February day.

At last he put his hand on the knob and opened the door infinitesimally; beneath his hand the door crept by inches and without any sound; still with that infinitesimal silence he put his eye to the crack and saw, lying upon the deep, rich pile of the corridor carpet, a bone. It was a cooked bone, a rib; to it still adhered close shreds of flesh holding in mute and overlapping halfmoons the marks of human teeth. Now that the door was open he could hear the voices too.

Still without any sound, with that infinite care, he raised and advanced the mirror. For an instant he caught his own reflection in it and he paused for a time and with a kind of cold unbelief he examined his own face — the face of the shrewd and courageous lighter, of that wellnigh infallible expert in the anticipation of and controlling of man and his doings, overlaid now with the baffled helplessness of a child.

Then he slanted the glass a little further until he could see the corridor reflected in it. Squatting and facing one another across the carpet as across a stream of water were two men. He did not know the faces, though he knew the Face, since he had looked upon it by day and dreamed upon it by night for three weeks now. It was a squat face, dark, a little flat, a little Mongol; secret, decorous, impenetrable, and grave.

He had seen it repeated until he had given up trying to count it or even estimate it; even now, though he could see the two men squatting before him and could hear the two quiet voices, it seemed to him that in some idiotic moment out of attenuated sleeplessness and strain he looked upon a single man facing himself in a mirror.

They wore beaver hats and new frock coats; save for the minor detail of collars and waistcoats they were impeccably dressed — though a little early — for the forenoon of the time, down to the waist. But from here down credulity, all sense of fitness and decorum, was outraged.

At a glance one would have said that they had come intact out of Pickwickian England, save that the tight, light-colored smallclothes ended not in Hessian boots nor in any boots at all, but in dark, naked feet.

On the floor beside each one lay a neatly rolled bundle of dark cloth; beside each bundle in turn, mute toe and toe and heel and heel, as though occupied by invisible sentries facing one another across the corridor, sat two pairs of new boots.

From a basket woven of whiteoak withes beside one of the squatting men there shot suddenly the snake-like head and neck of a game cock, which glared at the faint flash of the mirror with a round, yellow, outraged eye. It was from these that the voices came, pleasant, decorous, quiet:

“That rooster hasn’t done you much good up here.”

“That’s true. Still, who knows? Besides, I certainly couldn’t have left him at home, with those damned lazy Indians. I wouldn’t find a feather left. You know that. But it is a nuisance, having to lug this cage around with me day and night.”

“This whole business is a nuisance, if you ask me.”

“You said it. Squatting here outside this door all night long, without a gun or anything. Suppose bad men tried to get in during the night: what could we do? If anyone would want to get in. I don’t.”

“Nobody does. It’s for honor.”

“Whose honor? Yours? Mine? Frank Weddel’s?”

“White man’s honor. You don’t understand white people. They are like children: you have to handle them careful because you never know what they are going to do next. So if it’s the rule for guests to squat all night long in the cold outside this man’s door, we’ll just have to do it. Besides, hadn’t you rather be in here than out yonder in the snow in one of those damn tents?”

“You said it. What a climate. What a country. I wouldn’t have this town if they gave it to me.”

“Of course you wouldn’t. But that’s white men: no accounting for taste. So as long as we are here, we’ll have to try to act like these people believe that Indians ought to act. Because you never know until afterward just what you have done to insult or scare them. Like this having to talk white talk all the time. . . .”

The President withdrew the mirror and closed the door quietly. Once more he stood silent and motionless in the middle of the room, his head bent, musing, baffled yet indomitable: indomitable since this was not the first time that he had faced odds; baffled since he faced not an enemy in the open field, but was besieged within his very high and lonely office by them to whom he was, by legal if not divine appointment, father.

In the iron silence of the winter dawn he seemed, clairvoyant of walls, to be ubiquitous and one with the waking of the stately House. Invisible and in a kind of musing horror he seemed to be of each group of his Southern guests — that one squatting without the door, that larger one like so many figures carved of stone in the very rotunda itself of this concrete and visible apotheosis of the youthful Nation’s pride — in their new beavers and frock coats and woolen drawers.

With their neatly rolled pantaloons under their arms and their virgin shoes in the other hand; dark, timeless, decorous and serene beneath the astonished faces and golden braid, the swords and ribbons and stars, of European diplomats.

The President said quietly, “Damn. Damn. Damn.” He moved and crossed the room, pausing to take up his boots from where they sat beside a chair, and approached the opposite door. Again he paused and opened this door too quietly and carefully, out of the three weeks’ habit of expectant fatalism, though there was only his wife beyond it, sleeping peacefully in bed.

He crossed this room in turn, carrying his boots, pausing to replace the hand glass on the dressing table, among its companion pieces of the set which the new French Republic had presented to a predecessor, and tiptoed on and into the anteroom, where a man in a long cloak looked up and then rose, also in his stockings. They looked at one another soberly. “All clear?” the President said in a low tone.

“Yes, General.”

“Good. Did you . . .” The other produced a second long, plain cloak. “Good, good,” the President said. He swung the cloak about him before the other could move. “Now the . . .” This time the other anticipated him; the President drew the hat well down over his face. They left the room on tiptoe, carrying their boots in their hands.

The back stairway was cold; their stockinged toes curled away from the treads, their vaporized breath wisped about their heads. They descended quietly and sat on the bottom step and put on their boots.

Outside it still snowed; invisible against snow-colored sky and snow-colored earth, the flakes seemed to materialize with violent and silent abruptness against the dark orifice of the stables.

Each bush and shrub resembled a white balloon whose dark shroud lines descended, light and immobile, to the white earth. Interspersed among these in turn and with a certain regularity were a dozen vaguely tent-shaped mounds, from the ridge of each of which a small column of smoke rose into the windless snow, as if the snow itself were in a state of peaceful combustion. The President looked at these, once, grimly. “Get along,” he said.

The other, his head lowered and his cloak held closely about his face, scuttled on and ducked into the stable. Perish the day when these two words were applied to the soldier chief of a party and a nation, yet the President was so close behind him that their breaths made one cloud.

And perish the day when the word flight were so applied, yet they had hardly vanished into the stable when they emerged, mounted now and already at a canter, and so across the lawn and past the snow-hidden tents and toward the gates which gave upon that Avenue in embryo yet but which in time would be the stage upon which each four years would parade the proud panoply of the young Nation’s lusty man’s estate for the admiration and envy and astonishment of the weary world.

At the moment, though, the gates were occupied by those more immediate than splendid augurs of the future.

“Look out,” the other man said, reining back. They reined aside — the President drew the cloak about his face — and allowed the party to enter: the squat, broad, dark men dark against the