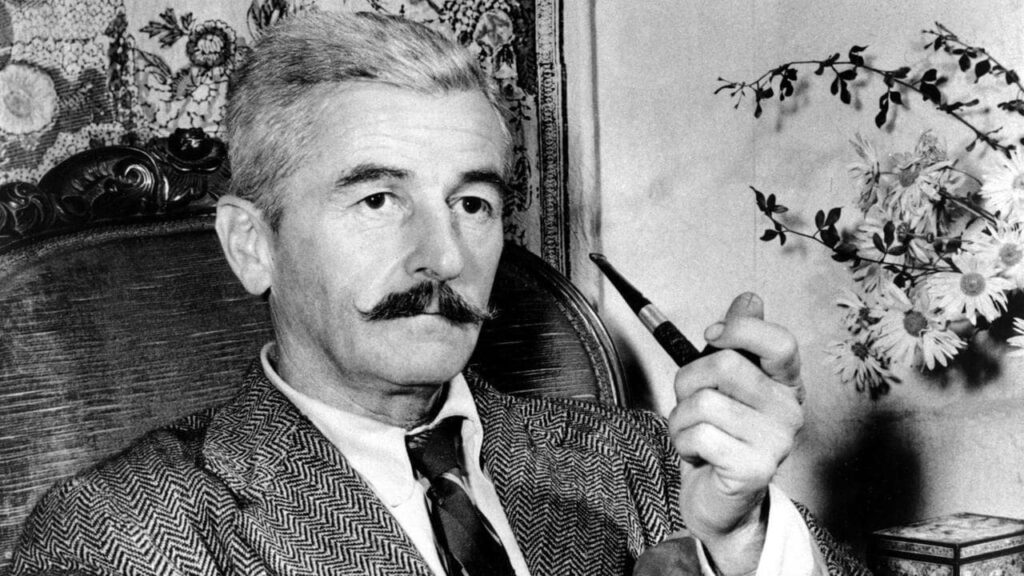

Mistral, William Faulkner

Mistral

I

IT WAS THE last of the Milanese brandy. I drank, and passed the bottle to Don, who lifted the flask until the liquor slanted yellowly in the narrow slot in the leather jacket, and while he held it so the soldier came up the path, his tunic open at the throat, pushing the bicycle.

He was a young man, with a bold lean face. He gave us a surly good day and looked at the flask a moment as he passed. We watched him disappear beyond the crest, mounting the bicycle as he went out of sight.

Don took a mouthful, then he poured the rest out. It splattered on the parched earth, pocking it for a fading moment. He shook the flask to the ultimate drop. “Salut,” he said, returning the flask. “Thanks, O gods. My Lord, if I thought I’d have to go to bed with any more of that in my stomach.”

“It’s too bad, the way you have to drink it,” I said. “Just have to drink it.” I stowed the flask away and we went on, crossing the crest. The path began to descend, still in shadow.

The air was vivid, filled with sun which held a quality beyond that of mere light and heat, and a sourceless goat bell somewhere beyond the next turn of the path, distant and unimpeded.

“I hate to see you lugging the stuff along day after day,” Don said. “That’s the reason I do. You couldn’t drink it, and you wouldn’t throw it away.”

“Throw it away? It cost ten lire. What did I buy it for?”

“God knows,” Don said. Against the sun-filled valley the trees were like the bars of a grate, the path a gap in the bars, the valley blue and sunny. The goat bell was somewhere ahead. A fainter path turned off at right angles, steeper than the broad one which we were following. “He went that way,” Don said.

“Who did?” I said. Don was pointing to the faint mark of bicycle tires where they had turned into the fainter path.

“See.”

“This one must not have been steep enough for him,” I said.

“He must have been in a hurry.”

“He sure was, after he made that turn.”

“Maybe there’s a haystack at the bottom.”

“Or he could run on across the valley and up the other mountain and then run back down that one and up this one again until his momentum gave out.”

“Or until he starved to death,” Don said.

“That’s right,” I said. “Did you ever hear of a man starving to death on a bicycle?”

“No,” Don said. “Did you?”

“No,” I said. We descended. The path turned, and then we came upon the goat bell. It was on a laden mule cropping with delicate tinkling jerks at the pathside near a stone shrine. Beside the shrine sat a man in corduroy and a woman in a bright shawl, a covered basket beside her. They watched us as we approached.

“Good day, signor,” Don said. “Is it far?”

“Good day, signori,” the woman said. The man looked at us. He had blue eyes with dissolving irises, as if they had been soaked in water for a long time. The woman touched his arm, then she made swift play with her fingers before his face. He said, in a dry metallic voice like a cicada’s:

“Good day, signori.”

“He doesn’t hear any more,” the woman said. “No, it is not far. From yonder you will see the roofs.”

“Good,” Don said. “We are fatigued. Might one rest here, signora?”

“Rest, signori,” the woman said. We slipped our packs and sat down. The sun slanted upon the shrine, upon the serene, weathered figure in the niche and upon two bunches of dried mountain asters lying there.

The woman was making play with her fingers before the man’s face. Her other hand in repose upon the basket beside her was gnarled and rough. Motionless, it had that rigid quality of unaccustomed idleness, not restful so much as quite spent, dead. It looked like an artificial hand attached to the edge of the shawl, as if she had donned it with the shawl for conventional complement. The other hand, the one with which she talked to the man, was swift and supple as a prestidigitator’s.

The man looked at us. “You walk, signori,” he said in his light, cadenceless voice.

“Sì,” we said. Don took out the cigarettes. The man lifted his hand in a slight, deprecatory gesture. Don insisted. The man bowed formally, sitting, and fumbled at the pack. The woman took the cigarette from the pack and put it into his hand. He bowed again as he accepted a light. “From Milano,” Don said. “It is far.”

“It is far,” the woman said. Her fingers rippled briefly. “He has been there,” she said.

“I was there, signori,” the man said. He held the cigarette carefully between thumb and forefinger. “One takes care to escape the carriages.”

“Yes.” Don said. “Those without horses.”

“Without horses,” the woman said. “There are many. Even here in the mountains we hear of it.”

“Many,” Don said. “Always whoosh. Whoosh. Whoosh.”

“Sì,” the woman said. “Even here I have seen it.” Her hand rippled in the sunlight. The man looked at us quietly, smoking. “It was not like that when he was there, you see,” she said.

“I am there long time ago, signori,” he said. “It is far.” He spoke in the same tone she had used, the same tone of grave and courteous explanation.

“It is far,” Don said. We smoked. The mule cropped with delicate, jerking tinkles of the bell. “But we can rest yonder,” Don said, extending his hand toward the valley swimming blue and sunny beyond the precipice where the path turned. “A bowl of soup, wine, a bed?”

The woman watched us across that serene and topless rampart of the deaf, the cigarette smoking close between thumb and finger. The woman’s hand flickered before his face. “Sì,” he said; “sì. With the priest: why not? The priest will take them in.” He said something else, too swift for me. The woman removed the checked cloth which covered the basket, and took out a wineskin. Don and I bowed and drank in turn, the man returning the bows.

“Is it far to the priest’s?” Don said.

The woman’s hand flickered with unbelievable rapidity. Her other hand, lying upon the basket, might have belonged to another body. “Let them wait for him there, then,” the man said. He looked at us. “There is a funeral today. You will find him at the church. Drink, signori.”

We drank in decorous turn, the three of us. The wine was harsh and sharp and potent. The mule cropped, its small bell tinkling, its shadow long in the slanting sun, across the path. “Who is it that’s dead, signora?” Don said.

“He was to have married the priest’s ward after this harvest,” the woman said; “the banns were read and all. A rich man, and not old. But two days ago, he died.”

The man watched her lips. “Tchk. He owned land, a house: so do I. It is nothing.”

“He was rich,” the woman said. “Because he was both young and fortunate, my man is jealous of him.”

“But not now,” the man said. “Eh, signori?”

“To live is good,” Don said. He said, e bello.

“It is good,” the man said; he also said, bello.

“He was to have married the priest’s niece, you say,” Don said.

“She is no kin to him,” the woman said. “The priest just raised her. She was six when he took her, without people, kin, of any sort. The mother was workhouse-bred. She lived in a hut on the mountain yonder. It was not known who the father was, although the priest tried for a long while to persuade one of them to marry her for the child’s—”

“One of which?” Don said.

“One of those who might have been the father, signor. But it was never known which one it was, until in 1916. He was a young man, a laborer; the next day we learned that the mother had gone too, to the war also, for she was never seen again by those who knew her until one of our boys came home after Caporetto, where the father had been killed, and told how the mother had been seen in a house in Milano that was not a good house.

So the priest went and got the child. She was six then, brown and lean as a lizard. She was hidden on the mountain when the priest got there; the house was empty. The priest pursued her among the rocks and captured her like a beast: she was half naked and without shoes and it winter time.”

“So the priest kept her,” Don said. “Stout fellow.”

“She had no people, no roof, no crust to call hers save what the priest gave her. But you would not know it. Always with a red or a green dress for Sundays and feast days, even at fourteen and fifteen, when a girl should be learning modesty and industry, to be a crown to her husband.

The priest had told that she would be for the church, and we wondered when he would make her put such away for the greater glory of God. But at fourteen and fifteen she was already the brightest and loudest and most tireless in the dances, and the young men already beginning to look after her, even after it had been arranged between her and him who is dead yonder.”

“The priest changed his mind about the church and got her a husband instead,” Don said.

“He found for her the best catch in this parish, signor. Young,