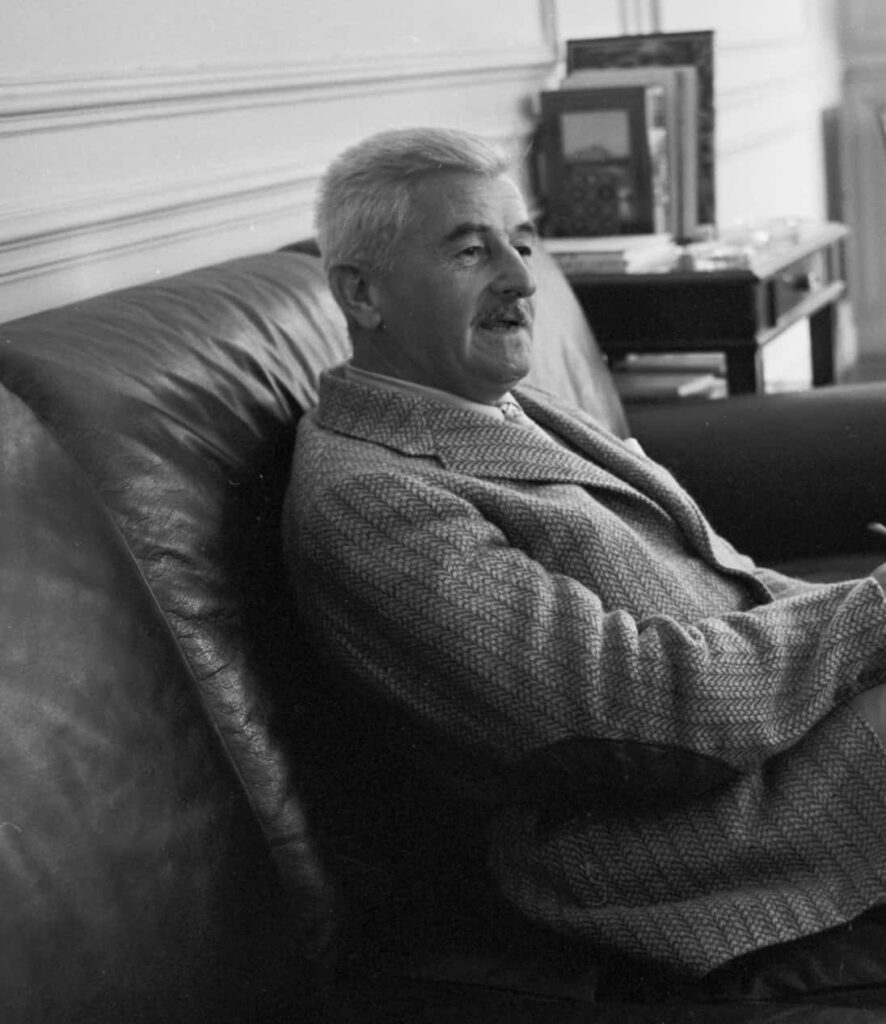

Mr. Acarius, William Faulkner

Mr. Acarius

The Saturday Evening Post, October 1965

MR. ACARIUS WAITED until toward the end of the afternoon, though he and his doctor had been classmates and fraternity brothers and still saw each other several times a week in the homes of the same friends and in the bars and lounges and grills of the same clubs, and he knew that he would have been sent straight in, no matter when he called. He was, almost immediately, to stand in his excellent sober Madison Avenue suit above the desk behind which his friend sat buried to the elbows in the paper end of the day, a reflector cocked rakishly above one ear and the other implements of his calling serpentined about the white regalia of his priesthood.

“I want to get drunk,” Mr. Acarius said.

“All right,” the doctor said, scribbling busily now at the foot of what was obviously a patient’s chart. “Give me ten minutes. Or why don’t you go on to the club and I’ll join you there.”

But Mr. Acarius didn’t move. He said, “Ab. Look at me,” in such a tone that the doctor thrust his whole body up and away from the desk in order to look up at Mr. Acarius standing over him.

“Say that again,” the doctor said. Mr. Acarius did so. “I mean in English,” the doctor said.

“I was fifty years old yesterday,” Mr. Acarius said. “I have just exactly what money I shall need to supply my wants and pleasures until the bomb falls. Except that when that occurs — I mean the bomb, of course — nothing will have happened to me in all my life. If there is any rubble left, it will be only the carcass of my Capehart and the frames of my Picassos.

Because there will never have been anything of me to have left any smudge or stain. Until now, that has contented me. Or rather, I have been resigned to accept it. But not any more. Before I have quitted this scene, vanished from the recollection of a few headwaiters and the membership lists of a few clubs—”

“Along with the headwaiters and the clubs,” the doctor said. “Predicating the bomb, of course.”

“Be quiet and listen,” Mr. Acarius said. “Before that shall have happened, I want to experience man, the human race.”

“Find yourself a mistress,” the doctor said.

“I tried that. Maybe what I want is debasement too.”

“Then in God’s name get married,” the doctor said. “What better way than that to run the whole gamut from garret to cellar and back again, not just once, but over again every day — or so they tell me.”

“Yes,” Mr. Acarius said. “So they tell you. I notice how the bachelor always says Try marriage, as he might advise you to try hashish. It’s the husband who always says Get married; videlicet: We need you.”

“Then get drunk,” the doctor said. “And may your shadow never grow less. And now I hope we have come at last to the nut. Just what do you want of me?”

“I want—” Mr. Acarius said. “I don’t just want—”

“You don’t just want to get tight, like back in school: Wake up tomorrow with nothing but a hangover, take two aspirins and a glass of tomato juice and drink all the black coffee you can hold, then at five P.M. a hair of the dog and now the whole business is over and forgotten until next time. You want to lie in a gutter in skid row without having to go down to skid row to do it.

You no more intend going down to skid row than you intend having skid row coming up the elevator to the twenty-second floor of the Barkman Tower. You would join skid row in its debasement, only you prefer to do yours on good Scotch whiskey. So there’s not just an esprit de sty; there’s a snobbery de sty too.”

“All right,” said Mr. Acarius.

“All right?”

“Yes then,” Mr. Acarius said.

“Then this is where we came in,” the doctor said. “Just what do you want of me?”

“I’m trying to tell you,” Mr. Acarius said. “I’m not just no better than the people on skid row. I’m not even as good, for the reason that I’m richer. Because I’m richer, I not only don’t have anything to escape from, driving me to try to escape from it, but as another cypher in the abacus of mankind, I am not even high enough in value to alter any equation by being subtracted from it. But at least I can go along for the ride, like the flyspeck on the handle of the computer, even if it can’t change the addition. At least I can experience, participate in, the physical degradation of escaping—”

“A sty in a penthouse,” the doctor said.

“ — the surrender, the relinquishment to and into the opium of escaping, knowing in advance the inevitable tomorrow’s inevitable physical agony; to have lost nothing of anguish but instead only to have gained it; to have merely compounded yesterday’s spirit’s and soul’s laceration with tomorrow’s hangover—”

“ — with a butler to pour your drink when you reach that stage and to pour you into the bed when you reach that stage, and to bring you the aspirin and the bromide after the three days or the four or whenever it will be that you will allow yourself to hold them absolved who set you in the world,” the doctor said.

“I didn’t think you understood,” Mr. Acarius said, “even if you were right about the good Scotch where his on skid row is canned heat. The butler and the penthouse will only do to start with, to do the getting drunk in. But after that, no more. Even if Scotch is the only debasement of which my soul is capable, the anguish of my recovery from it will be at least a Scotch approximation of his who had nothing but canned heat with which to face the intolerable burden of his soul.”

“What in the world are you talking about?” the doctor said. “Do you mean that you intend to drink yourself into Bellevue?”

“Not Bellevue,” Mr. Acarius said. “Didn’t we both agree that I am incapable of skid row? No, no: One of those private places, such as the man from skid row will never and can never see, whose at best is a grating or a vacant doorway, and at worst a police van and the — what do they call it? — bullpen. A Scotch bullpen of course, since that’s all I am capable of. But it will have mankind in it, and I shall have entered mankind.”

“Say that again,” the doctor said. “Try that in English too.”

“That’s all,” Mr. Acarius said. “Mankind. People. Man. I shall be one with man, victim of his own base appetites and now struggling to extricate himself from that debasement. Maybe it’s even my fault that I’m incapable of anything but Scotch, and so our bullpen will be a Scotch one where for a little expense we can have peace, quiet for the lacerated and screaming nerves, sympathy, understanding—”

“What?” the doctor said.

“ — and maybe what my fellow inmates are trying to escape from — the too many mistresses or wives or the too much money or responsibility or whatever else it is that drives into escape the sort of people who can afford to pay fifty dollars a day for the privilege of escaping — will not bear mention in the same breath with that which drives one who can afford no better, even to canned heat.

But at least we will be together in having failed to escape and in knowing that in the last analysis there is no escape, that you can never escape and, whether you will or not, you must reenter the world and bear yourself in it and its lacerations and all its anguish of breathing, to support and comfort one another in that knowledge and that attempt.”

“What?” the doctor said. “What’s that?”

“I beg pardon?” said Mr. Acarius.

“Do you really believe that that’s what you are going to find in this place?”

“Why not?”

“Then I beg yours,” the doctor said. “Go on.”

“That’s all,” Mr. Acarius said. “That’s what I want of you. You must know any number of these places. The best—”

“The best,” the doctor said. “Of course.” He reached for the telephone. “Yes, I know it.”

“Shouldn’t I see it first?”

“What for? They’re all alike. You’ll have seen plenty of this one before you’re out again.”

“I thought you said that this one would be the best,” Mr. Acarius said.

“Right,” the doctor said, removing his hand from the telephone. It did not take them long: an address in an expensive section facing the Park, itself outwardly resembling just another expensive apartment house not too different from that one in (or on) which Mr. Acarius himself lived, the difference only beginning inside and even there not too great: A switchboard in a small foyer enclosed by the glass-panel walls of what were obviously offices.

Apparently the doctor read Mr. Acarius’s expression. “Oh, the drunks,” the doctor said. “They’re all upstairs. Unless they can walk, they bring them in the back way. And even when they can walk in, they don’t see this very long nor but twice. Well?” Then the doctor read that one too. “All right. We’ll see Hill too. After all, if you’re going to surrender your amateur’s virginity in debauchery, you are certainly entitled to examine at least the physiognomy of the supervisor of the rite.”

Doctor Hill was no older than Mr. Acarius’s own doctor; apparently there was