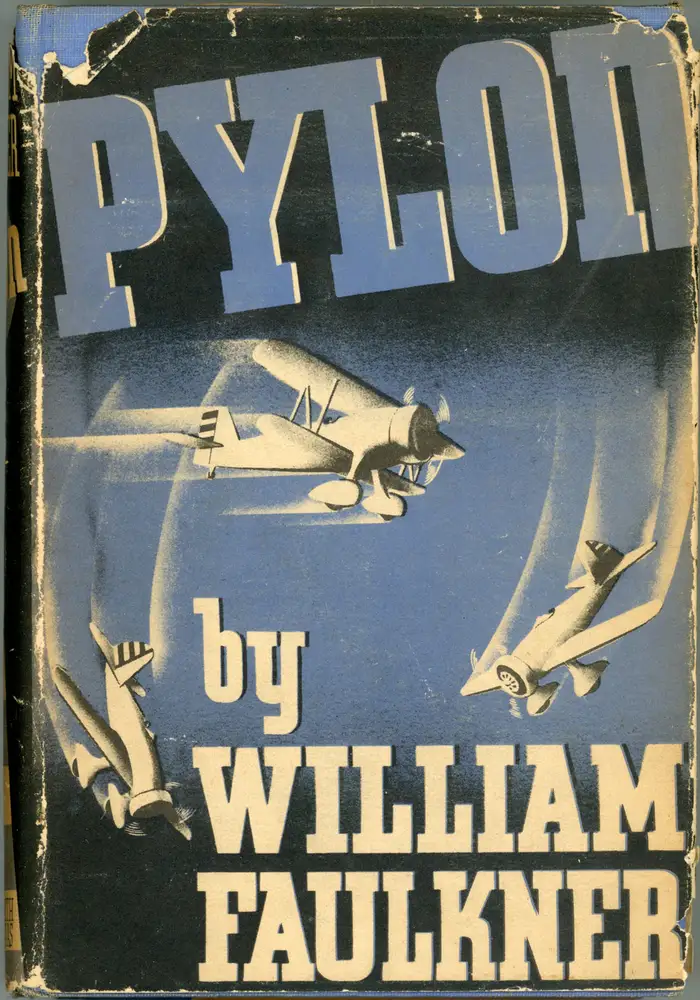

Pylon, William Faulkner

Pylon

First published in 1935, Faulkner’s seventh novel is set in New Valois, a fictionalised version of New Orleans. It tells the story of a group of barnstormers (pilots that performed tricks in aviation groups known as flying circuses), whose lives are thoroughly unconventional. The ‘pylon’ of the title is the tower around which a pilot must turn as he competes in a race at an air fair. Though less famous than many of his other works, Pylon is one of Faulkner’s most exciting books, set against the colourful backdrop of Mardi Gras.

The plot concerns how a flying team, comprising a pilot, a “jumper,” or parachutist, and a mechanic, accompanied by a woman and her son, are short of money and hope to win at least one of the prizes at an air show. They live only on their winnings and they often have no place to stay, little to eat and no funds for transportation within the city.

Although the novel deals with the “romance” of flying, the hard physical conditions of the performers are never far from our view. The text examines Faulkner’s concept of psychological necessity — that men and women must do what they are driven to do by their most profound inner motivations. Faulkner achieves this through solid, complex characters, who differ widely from one another and are sourced from a broad variety of social strata.

Contents

Dedication of an Airport

An Evening in New Valois

Night in the Vieux Carré

To-Morrow

And To-morrow

Love-song of J. A. Prufrock

The Scavengers

Dedication of an Airport

FOR A FULL minute Jiggs stood before the window in a light spatter of last night’s confetti lying against the window-base like spent dirty foam, light-poised on the balls of his grease-stained tennis shoes, looking at the boots.

Slant-shimmered by the intervening plate they sat upon their wooden pedestal in unblemished and inviolate implication of horse and spur, of the posed country-life photographs in the magazine advertisements, beside the easel-wise cardboard placard with which the town had bloomed overnight as it had with the purple-and-gold tissue bunting and the trodden confetti and broken serpentine… the same lettering, the same photographs of the trim vicious fragile aeroplanes and the pilots leaning upon them in gargantuan irrelation as if the aeroplanes were a species of esoteric and fatal animals not trained or tamed but just for the instant inert, above the neat brief legend of name and accomplishment or perhaps just hope.

He entered the store, his rubber soles falling in quick hissing thuds on pavement and iron sill and then upon the tile floor of that museum of glass cases lighted suave and sourceless by an unearthly day-coloured substance in which the hats and ties and shirts, the belt-buckles and cuff-links and handkerchiefs, the pipes shaped like golf-clubs and the drinking-tools shaped like boots and barnyard fowls and the minute impedimenta for wear on ties and vest-chains shaped like bits and spurs, resembled biologic specimens put into the inviolate preservative before they had ever been breathed into. “Boots?” the clerk said. “The pair in the window?”

“Yair,” Jiggs said. “How much?” But the clerk did not even move. He leaned back on the counter, looking down at the hard tough short-chinned face, blue-shaven, with a long thread-like and recently stanched razor-cut on it and in which the hot brown eyes seemed to snap and glare like a boy’s approaching for the first time the aerial wheels and stars and serpents of a night time carnival; at the filthy raked swaggering peaked cap, the short thick muscle-bound body like the photographs of the one who two years before was light-middleweight champion of the army or Marine Corps or navy; the cheap breeches overcut to begin with and now skin-tight as if both they and their wearer had been recently and hopelessly rained on and enclosing a pair of short stocky thick fast legs like a polo pony’s, which descended into the tops of a pair of boots, footless now and secured by two riveted straps beneath the insteps of the tennis shoes.

“They are twenty-two and a half,” the clerk said.

“All right. I’ll take them. How late do you keep open at night?”

“Until six.”

“Hell! I’ll be out at the airport then. I won’t get back to town until seven. How about getting them then?” Another clerk came up: the manager, the floor-walker.

“You mean you don’t want them now?” the first said.

“No,” Jiggs said. “How about getting them at seven?”

“What is it?” the second clerk said.

“Says he wants a pair of boots. Says he can’t get back from the airport before seven o’clock.”

The second looked at Jiggs. “You a flyer?”

“Yair,” Jiggs said. “Listen. Leave a guy here. I’ll be back by seven. I’ll need them to-night.”

The second also looked down at Jiggs’ feet. “Why not take them now?”

Jiggs didn’t answer at all. He just said, “So I’ll have to wait until to-morrow.”

“Unless you can get back before six,” the second said. “O.K.,” Jiggs said. “All right, mister. How much do you want down?” Now they both looked at him: at the face, the hot eyes: the entire appearance articulate and complete, badge regalia and passport, of an oblivious and incorrigible insolvency. “To keep them for me. That pair in the window.”

The second looked at the first. “Do you know his size?”

“That’s all right about that,” Jiggs said. “How much?”

The second looked at Jiggs. “You pay ten dollars and we will hold them for you until to-morrow.”

“Ten dollars? Jesus, mister. You mean ten per cent. I could pay ten per cent, down and buy an aeroplane.”

“You want to pay ten per cent, down?”

“Yair. Ten per cent. Call for them this afternoon if I can get back from the airport in time.”

“That will be two and a quarter,” the second said. When Jiggs put his hand into his pocket they could follow it, fingernail and knuckle, the entire length of the pocket, like watching the ostrich in the movie cartoon swallow the alarm clock. It emerged a fist and opened upon a wadded dollar bill and coins of all sizes. He put the bill into the first clerk’s hand and began to count the coins on to the bill.

“There’s fifty,” he said. “Seventy-five. And fifteen’s ninety, and twenty-five is…” His voice stopped; he became motionless, with the twenty-five-cent piece in his left hand and a half-dollar and four nickels on his right palm. The clerks watched him put the quarter back into his right hand and take up the four nickels. “Let’s see,” he said. “We had ninety, and twenty will be…”

“Two dollars and ten cents,” the second said. “Take back two nickels and give him the quarter.”

“Two and a dime,” Jiggs said. “How about taking that down?”

“You were the one who suggested ten per cent.”

“I can’t help that. How about two and a dime?”

“Take it,” the second said. The first took the money and went away. Again the second watched Jiggs’ hand move downward along his leg, and then he could even see the two coins at the end of the pocket, through the soiled cloth.

“Where do you get this bus to the airport?” Jiggs said. The other told him. Now the first returned, with the cryptic scribbled duplicate of the sale; and now they both looked into the hot interrogation of the eyes.

“They will be ready for you when you call,” the second said. “Yair; sure,” Jiggs said. “But get them out of the window.”

“You want to examine them?”

“No. I just want to see them come out of that window.” So again outside the window, his rubber soles resting upon that light confetti spatter more forlorn than spattered paint since it had neither inherent weight nor cohesiveness to hold it anywhere, which even during the time that Jiggs was in the store had decreased, thinned, vanishing particle by particle into nothing like foam does, he stood until the hand came into the window and drew the boots out.

Then he went on, walking fast with his short bouncing curiously stiff-kneed gait. When he turned into Grandlieu Street he could see a clock, though he was already hurrying or rather walking at his fast stiff hard gait like a mechanical toy that has but one speed, and though the clock’s face was still in the shadow of the opposite street side and what sunlight there was was still high, diffused, suspended in soft refraction by the heavy damp bayou-and-swamp-suspired air.

There was confetti here too, and broken serpentine, in neat narrow swept windrows against wall angles and lightly vulcanized along the gutter rims by the flushing fireplugs of the past dawn, while, upcaught and pinned by the cryptic significant shields to door-front and lamp-post, the purple-and-gold bunting looped unbroken as a trolley wire above his head as he walked, turning at last at right angles to cross the street itself and meet that one on the opposite side making its angle too, to join over the centre of the street as though to form an aerial and bottomless regal-coloured cattle chute suspended at first floor level above the earth, and suspending beneath itself in turn, the outward-facing cheese-cloth-lettered interdiction which Jiggs, passing, slowed looking back to read: Grandlieu Street CLOSED To Traffic 8.0 P.M. — Midnight.

Now he could see the bus at the kerb, where they had told him it would be, with its cloth banner fastened by the four corners across its broad stem to ripple and flap in motion, and the wooden sandwich board at the kerb too: Bluehound to Feinman Airport 15c. The driver stood beside the open door; he too watched Jiggs’ knuckles travel the length of the