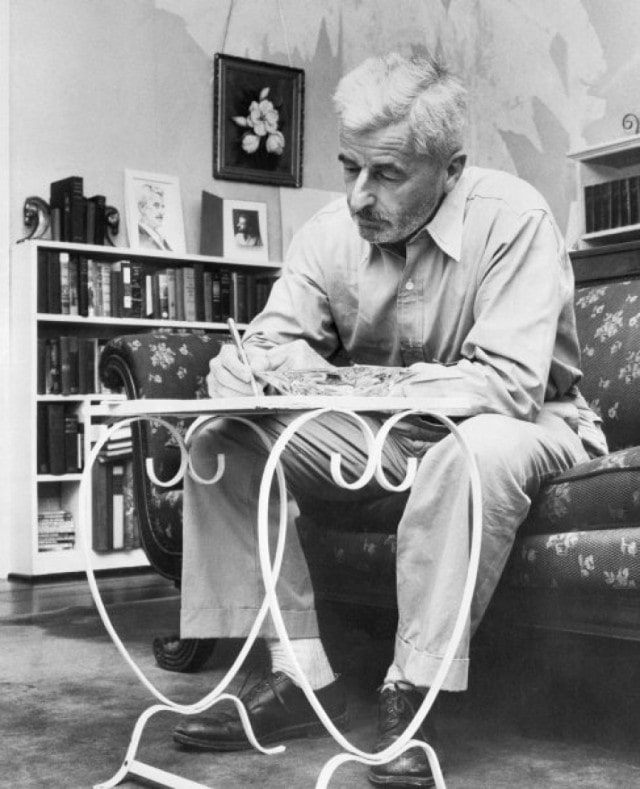

The Brooch, William Faulkner

The Brooch

THE TELEPHONE WAKED him. He waked already hurrying, fumbling in the dark for robe and slippers, because he knew before waking that the bed beside his own was still empty, and the instrument was downstairs just opposite the door beyond which his mother had lain propped upright in bed for five years, and he knew on waking that he would be too late because she would already have heard it, just as she heard everything that happened at any hour in the house.

She was a widow, he the only child. When he went away to college she went with him; she kept a house in Charlottesville, Virginia, for four years while he graduated. She was the daughter of a well-to-do merchant. Her husband had been a travelling man who came one summer to the town with letters of introduction: one to a minister, the other to her father. Three months later the travelling man and the daughter were married. His name was Boyd.

He resigned his position within the year and moved into his wife’s house and spent his days sitting in front of the hotel with the lawyers and the cotton-planters — a dark man with a gallant swaggering way of removing his hat to ladies. In the second year, the son was born.

Six months later, Boyd departed. He just went away, leaving a note to his wife in which he told her that he could no longer bear to lie in bed at night and watch her rolling onto empty spools the string saved from parcels from the stores. His wife never heard of him again, though she refused to let her father have the marriage annulled and change the son’s name.

Then the merchant died, leaving all his property to the daughter and the grandson who, though he had been out of Fauntleroy suits since he was seven or eight, at twelve wore even on weekdays clothes which made him look not like a child but like a midget; he probably could not have long associated with other children even if his mother had let him.

In due time the mother found a boys’ school where the boy could wear a round jacket and a man’s hard hat with impunity, though by the time the two of them removed to Charlottesville for these next four years, the son did not look like a midget.

He looked now like a character out of Dante — a man a little slighter than his father but with something of his father’s dark handsomeness, who hurried with averted head, even when his mother was not with him, past the young girls on the streets not only of Charlottesville but of the little lost Mississippi hamlet to which they presently returned, with an expression of face like the young monks or angels in fifteenth-century allegories.

Then his mother had her stroke, and presently the mother’s friends brought to her bed reports of almost exactly the sort of girl which perhaps even the mother might have expected the son to become not only involved with but to marry.

Her name was Amy, daughter of a railroad conductor who had been killed in a wreck. She lived now with an aunt who kept a boarding-house — a vivid, daring girl whose later reputation was due more to folly and the caste handicap of the little Southern town than to badness and which at the last was doubtless more smoke than fire; whose name, though she always had invitations to the more public dances, was a light word, especially among the older women, daughters of decaying old houses like this in which her future husband had been born.

So presently the son had acquired some skill in entering the house and passing the door beyond which his mother lay propped in bed, and mounting the stairs in the dark to his own room. But one night he failed to do so.

When he entered the house the transom above his mother’s door was dark, as usual, and even if it had not been he could not have known that this was the afternoon on which the mother’s friends had called and told her about Amy, and that his mother had lain for five hours, propped bolt upright, in the darkness, watching the invisible door.

He entered quietly as usual, his shoes in his hand, yet he had not even closed the front door when she called his name. Her voice was not raised. She called his name once:

“Howard.”

He opened the door. As he did so the lamp beside her bed came on. It sat on a table beside the bed; beside it sat a clock with a dead face; to stop it had been the first act of his mother when she could move her hands two years ago. He approached the bed from which she watched him — a thick woman with a face the color of tallow and dark eyes apparently both pupil-less and iris-less beneath perfectly white hair. “What?” he said. “Are you sick?”

“Come closer,” she said. He came nearer. They looked at one another. Then he seemed to know; perhaps he had been expecting it.

“I know who’s been talking to you,” he said. “Those damned old buzzards.”

“I’m glad to hear it’s carrion,” she said. “Now I can rest easy that you won’t bring it into our house.”

“Go on. Say, your house.”

“Not necessary. Any house where a lady lives.” They looked at one another in the steady lamp which possessed that stale glow of sickroom lights. “You are a man. I don’t reproach you. I am not even surprised. I just want to warn you before you make yourself ridiculous. Don’t confuse the house with the stable.”

“With the — Hah!” he said. He stepped back and jerked the door open with something of his father’s swaggering theatricalism. “With your permission,” he said. He did not close the door. She lay bolt upright on the pillows and looked into the dark hall and listened to him go to the telephone, call the girl, and ask her to marry him tomorrow. Then he reappeared at the door.

“With your permission,” he said again, with that swaggering reminiscence of his father, closing the door. After a while the mother turned the light off. It was daylight in the room then.

They were not married the next day, however. “I’m scared to,” Amy said. “I’m scared of your mother. What does she say about me?”

“I don’t know. I never talk to her about you.”

“You don’t even tell her you love me?”

“What does it matter? Let’s get married.”

“And live there with her?” They looked at one another. “Will you go to work, get us a house of our own?”

“What for? I have enough money. And it’s a big house.”

“Her house. Her money.”

“It’ll be mine — ours some day. Please.”

“Come on. Let’s try to dance again.” This was in the parlor of the boarding-house, where she was trying to teach him to dance, but without success. The music meant nothing to him; the noise of it or perhaps the touch of her body destroyed what little co-ordination he could have had. But he took her to the Country Club dances; they were known to be engaged. Yet she still staid out dances with other men, in the parked cars about the dark lawn. He tried to argue with her about it, and about drinking.

“Sit out and drink with me, then,” he said.

“We’re engaged. It’s no fun with you.”

“Yes,” he said, with the docility with which he accepted each refusal; then he stopped suddenly and faced her. “What’s no fun with me?” She fell back a little as he gripped her shoulder. “What’s no fun with me?”

“Oh,” she said. “You’re hurting me!”

“I know it. What’s no fun with me?”

Then another couple came up and he let her go. Then an hour later, during an intermission, he dragged her, screaming and struggling, out of a dark car and across the dance floor, empty now and lined with chaperones like a theater audience, and drew out a chair and took her across his lap and spanked her. By daylight they had driven twenty miles to another town and were married.

That morning Amy called Mrs. Boyd “Mother” for the first and (except one, and that perhaps shocked out of her by surprise or perhaps by exultation) last time, though the same day Mrs. Boyd formally presented Amy with the brooch: an ancient, clumsy thing, yet valuable. Amy carried it back to their room, and he watched her stand looking at it, perfectly cold, perfectly inscrutable. Then she put it into a drawer. She held it over the open drawer with two fingers and released it and then drew the two fingers across her thigh.

“You will have to wear it sometimes,” Howard said.

“Oh, I will. I’ll show my gratitude. Don’t worry.” Presently it seemed to him that she took pleasure in wearing it. That is, she began to wear it quite often. Then he realized that it was not pleasure but vindictive incongruity; she wore it for an entire week once on the bosom of a gingham house dress, an apron. But she always wore it where Mrs. Boyd would see it, always when she and Howard had dressed to go out and would stop in the mother’s room to say good night.

They lived upstairs, where, a year later, their child was born. They took the child down for Mrs. Boyd to see it. She turned her head on the pillows and looked at the child once. “Ah,” she said. “I never