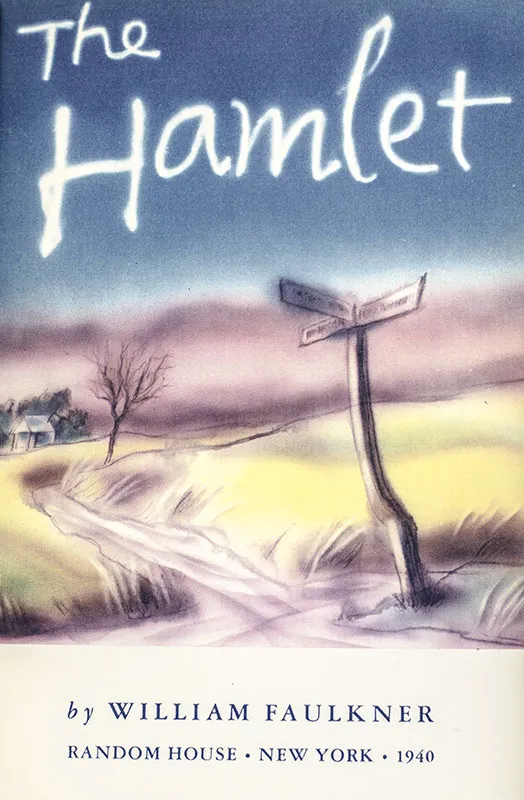

The Hamlet, William Faulkner

The Hamlet

Published in 1940, this novel forms part of what is now collectively known as the Snopes Trilogy, though it was originally a standalone novel. It was followed by The Town (1957) and The Mansion (1959). The novel incorporates revised versions of the previously-published short stories “Spotted Horses” (1931, Book Four’s Chapter One), “The Hound” (1931, Book Three’s Chapter Two), “Lizards in Jamshyd’s Courtyard” (1932, Book One’s Chapter Three and Book Four’s Chapter Two), and “Fool About a Horse” (1936, Book One’s Chapter Two). It also makes use of material from “Father Abraham” (abandoned 1927, pub. 1984, Book Four’s Chapter One), “Afternoon of a Cow” (1937, pub. 1943, Book Three’s Chapter Two), and “Barn Burning” (1939, Book One’s Chapter One).

The plot concerns the exploits of the Snopes family, beginning with Ab Snopes, who is introduced more fully in Faulkner’s The Unvanquished. Most of the novel centres on Frenchman’s Bend, into which the heirs of Ab and his family have migrated from parts unknown. In the beginning of the book, Ab, his wife, daughter and son Flem settle down as tenant farmers beholden to the powerful Varner family. As the narrative progresses, the Snopeses move from being poor outcasts to a controversial, if not dangerous, element in the life of the town. In contrast, V.K. Ratliff stands as the moral hero of the novel. Faulkner employs the eccentricities of the Snopeses to great comic effect, most notably in his description of Ike Snopes and his carnal inclinations toward a cow.

Contents

BOOK ONE. FLEM

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

BOOK TWO. EULA

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

BOOK THREE. THE LONG SUMMER

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

BOOK FOUR. THE PEASANTS

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

To Phil Stone

BOOK ONE. FLEM

CHAPTER ONE

FRENCHMAN’S BEND WAS a section of rich river-bottom country lying twenty miles southeast of Jefferson. Hill-cradled and remote, definite yet without boundaries, straddling into two counties and owning allegiance to neither, it had been the original grant and site of a tremendous pre-Civil War plantation, the ruins of which — the gutted shell of an enormous house with its fallen stables and slave quarters and overgrown gardens and brick terraces and promenades — were still known as the Old Frenchman’s place, although the original boundaries now existed only on old faded records in the Chancery Clerk’s office in the county courthouse in Jefferson, and even some of the once-fertile fields had long since reverted to the cane-and-cypress jungle from which their first master had hewed them.

He had quite possibly been a foreigner, though not necessarily French, since to the people who had come after him and had almost obliterated all trace of his sojourn, anyone speaking the tongue with a foreign flavour or whose appearance or even occupation was strange, would have been a Frenchman regardless of what nationality he might affirm, just as to their more urban co-evals (if he had elected to settle in Jefferson itself, say) he would have been called a Dutchman.

But now nobody knew what he had actually been, not even Will Varner, who was sixty years old and now owned a good deal of his original grant, including the site of his ruined mansion. Because he was gone now, the foreigner, the Frenchman, with his family and his slaves and his magnificence. His dream, his broad acres were parcelled out now into small shiftless mortgaged farms for the directors of Jefferson banks to squabble over before selling finally to Will Varner, and all that remained of him was the river bed which his slaves had straightened for almost ten miles to keep his land from flooding, and the skeleton of the tremendous house which his heirs-at-large had been pulling down and chopping up — walnut newel-posts and stair spindles, oak floors which fifty years later would have been almost priceless, the very clapboards themselves — for thirty years now for firewood.

Even his name was forgotten, his pride but a legend about the land he had wrested from the jungle and tamed as a monument to that appellation which those who came after him in battered wagons and on mule-back and even on foot, with flintlock rifles and dogs and children and home-made whiskey stills and Protestant psalm-books, could not even read, let alone pronounce, and which now had nothing to do with any once-living man at all — his dream and his pride now dust with the lost dust of his anonymous bones, his legend but the stubborn tale of the money he buried somewhere about the place when Grant overran the country on his way to Vicksburg.

The people who inherited from him came from the northeast, through the Tennessee mountains by stages marked by the bearing and raising of a generation of children. They came from the Atlantic seaboard and before that, from England and the Scottish and Welsh Marches, as some of the names would indicate — Turpin and Haley and Whittington, McCallum and Murray and Leonard and Littlejohn, and other names like Riddup and Armstid and Doshey which could have come from nowhere since certainly no man would deliberately select one of them for his own. They brought no slaves and no Phyfe and Chippendale highboys; indeed, what they did bring most of them could (and did) carry in their hands. They took up land and built one- and two-room cabins and never painted them, and married one another and produced children and added other rooms one by one to the original cabins and did not paint them either, but that was all.

Their descendants still planted cotton in the bottom land and corn along the edge of the hills and in the secret coves in the hills made whiskey of the corn and sold what they did not drink. Federal officers went into the country and vanished. Some garment which the missing man had worn might be seen — a felt hat, a broadcloth coat, a pair of city shoes or even his pistol — on a child or an old man or woman. County officers did not bother them at all save in the heel of election years. They supported their own churches and schools, they married and committed infrequent adulteries and more frequent homicides among themselves and were their own courts judges and executioners. They were Protestants and Democrats and prolific; there was not one negro landowner in the entire section. Strange negroes would absolutely refuse to pass through it after dark.

Will Varner, the present owner of the Old Frenchman place, was the chief man of the country. He was the largest landholder and beat supervisor in one county and Justice of the Peace in the next and election commissioner in both, and hence the fountainhead if not of law at least of advice and suggestion to a countryside which would have repudiated the term constituency if they had ever heard it, which came to him, not in the attitude of What must I do but What do you think you would like for me to do if you was able to make me do it. He was a farmer, a usurer, a veterinarian; Judge Benbow of Jefferson once said of him that a milder-mannered man never bled a mule or stuffed a ballot box.

He owned most of the good land in the country and held mortgages on most of the rest. He owned the store and the cotton gin and the combined grist mill and blacksmith shop in the village proper and it was considered, to put it mildly, bad luck for a man of the neighbourhood to do his trading or gin his cotton or grind his meal or shoe his stock anywhere else. He was thin as a fence rail and almost as long, with reddish-grey hair and moustaches and little hard bright innocently blue eyes; he looked like a Methodist Sunday School superintendent who on weekdays conducted a railroad passenger train or vice versa and who owned the church or perhaps the railroad or perhaps both. He was shrewd, secret and merry, of a Rabelaisian turn of mind and very probably still sexually lusty (he had fathered sixteen children to his wife, though only two of them remained at home, the others scattered, married and buried, from El Paso to the Alabama line) as the spring of his hair which even at sixty was still more red than grey, would indicate.

He was at once active and lazy; he did nothing at all (his son managed all the family business) and spent all his time at it, out of the house and gone before the son had come down to breakfast even, nobody knew where save that he and the old fat white horse which he rode might be seen anywhere within the surrounding ten miles at any time, and at least once every month during the spring and summer and early fall, the old white horse tethered to an adjacent fence post, he would be seen by someone sitting in a home-made chair on the jungle-choked lawn of the Old Frenchman’s homesite.

His blacksmith had made the chair for him by sawing an empty flour-barrel half through the middle and trimming out the sides and nailing a seat into it, and Varner would sit there chewing his tobacco or smoking his cob pipe, with a brusque word for passers cheerful enough but inviting no company, against his background of fallen baronial splendour. The people (those who saw him sitting there and those who were told about it) all believed that he sat there planning his next mortgage foreclosure in private, since it was only to an itinerant sewing-machine agent named Ratliff —