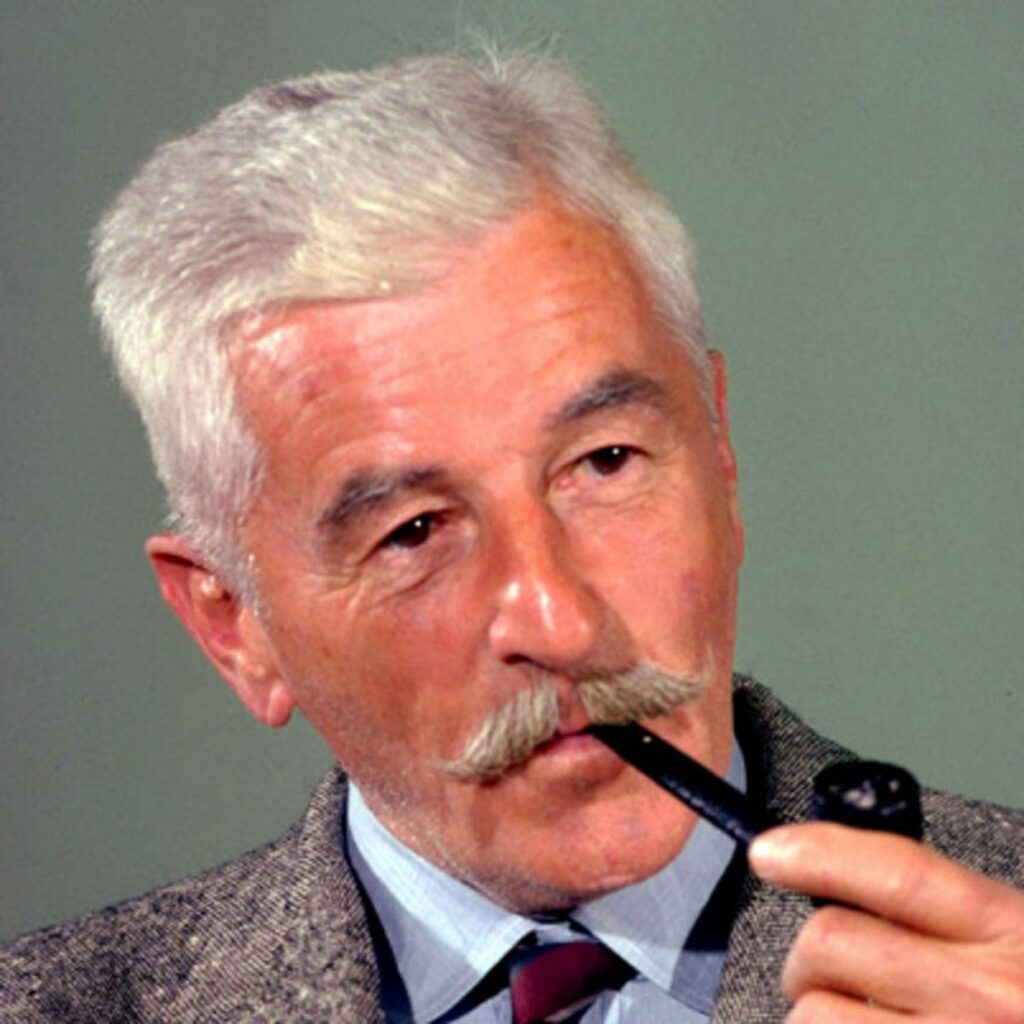

Thrift, William Faulkner

Thrift

The Saturday Evening Post, September 1930

I

In messes they told of MacWyrglinchbeath how, a first-class air mechanic of a disbanded Nieuport squadron, he went three weeks’ A.W.O.L. He had been given a week’s leave for England while the squadron was being reequipped with British-made machines, and he was last seen in Boulogne, where the lorry set him and his mates down. That night he disappeared. Three weeks later the hitherto unchallenged presence of an unidentifiable first-class air mechanic was discovered in the personnel of a bombing squadron near Boulogne.

At the ensuing investigation the bomber gunnery sergeant told how the man had appeared among the crew one morning on the beach, where the flight had landed after a raid. Replacements had come up the day before, and the sergeant said he took the man to be one of the replacements; it appeared that everyone took the man to be one of the new mechanics. He told how the man showed at once a conscientious aptitude, revealing an actual affection for the aeroplane of whose crew he made one, speaking in a slow, infrequent, Scottish voice of the amount of money it represented and of the sinfulness of sending so much money into the air in a single lump.

“He even asked to be put on flying,” the sergeant testified. “He downright courted me till I did it, volunteering for all manner of off-duty jobs for me, until I put him on once or twice. I’d keep him with me, on the toggles, though.”

They did not discover that anything was wrong until pay day. His name was not on the pay officer’s list; the man’s insistence — his was either sublime courage or sublime effrontery — brought his presence to the attention of the squadron commander. But when they looked for him, he was gone.

The next day, in Boulogne, an air mechanic with a void seven-day pass, issued three weeks ago by a now disbanded scout squadron, was arrested while trying to collect three weeks’ pay, which he said was owing to him, from the office of the acting provost marshal himself. His name, he said, was MacWyrglinchbeath.

Thus it was discovered that MacWyrglinchbeath was a simultaneous deserter from two different military units. He repeated his tale — for the fifth time in three days fetched from his cell by a corporal and four men with bayoneted rifles — standing bareheaded to attention before the table where a general now sat, and the operations officer of the bomber squadron and the gunnery sergeant:

“A had gone doon tae thae beach tae sleep, beca’ A kenned they wud want money for-r thae beds in the town. A was ther-re when thae boombers cam’ doon. Sae A went wi’ thae boombers.”

“But why didn’t you go home on your leave?” the general asked.

“A wou’na be spendin’ sic useless money, sir-r.”

The general looked at him. The general had little pig’s eyes, and his face looked as though it had been blown up with a bicycle pump.

“Do you mean to tell me that you spent seven days’ leave and a fortnight more without leave, as the member of the personnel of another squadron?”

“Well, sir-r,” MacWyrglinchbeath said, “naught wud do they but A sud tak’ thae week’s fur-rlough. I didna want it. And wi’ thae big machines A cud get flying pay.”

The general looked at him. Rigid, motionless, he could see the general’s red face swell and swell.

“Get that man out of here!” the general said at last.

“ ‘Bout face,” the corporal said.

“Get me that squadron commander,” the general said. “At once! I’ll cashier him! Gad’s teeth, I’ll put him in jail for the rest of his life!”

“ ‘Bout face!” the corporal said, a little louder. MacWyrglinchbeath had not moved.

“Sir-r,” he said. The general, in mid-voice, looked at him, his mouth still open a little. Behind his mustache he looked like a boar in a covert. “Sir-r,” MacWyrglinchbeath said, “wull A get ma pay for thae thr-r-ree weeks and thae seven hour-rs and for-rty minutes in the air-r?”

It was Ffollansbye, who was to first recommend him for a commission, who knew most about him.

“I give you,” he said, “a face like a ruddy walnut, maybe sixteen, maybe fifty-six; squat, with arms not quite as long as an ape’s, lugging petrol tins across the aerodrome. So long his arms were that he would have to hunch his shoulders and bow his elbows a little so the bottoms of the tins wouldn’t scrape the ground. He walked with a limp — he told me about that. It was just after they came down from Stirling in ‘14. He had enlisted for infantry; they had not told him that there were other ways of going in.

“So he began to make inquiries. Can’t you see him, listening to all the muck they told recruits then, about privates not lasting two days after reaching Dover — they told him, he said, that the enemy killed only the English and Irish and Lowlanders; the Highlands having not yet declared war — and such.

Anyway, he took it all in, and then he would go to bed at night and sift it out. Finally he decided to go for the Flying Corps; decided with pencil and paper that he would last longer there and so have more money saved. You see, neither courage nor cowardice had ever functioned in him at all; I don’t believe he had either. He was just like a man who, lost for a time in a forest, picks up a fagot here and there against the possibility that he might some day emerge.

“He applied for transfer, but they threw it out. He must have been rather earnest about it, for they finally explained that he must have a better reason than personal preference for desiring to transfer, and that a valid reason would be mechanical knowledge or a disability leaving him unfit for infantry service.

“So he thought that out. And the next day he waited until the barracks was empty, prodded the stove to a red heat, removed his boot and putty, and laid the sole of his foot to the stove.

“That was where the limp came from. When his transfer went through and he came out with his third-class air mechanic’s rating, they thought that he had been out before.

“I can see him, stiff at attention in the squadron office, his b. o. on the table, Whiteley and the sergeant trying to pronounce his name.

“ ‘What’s the name, sergeant?’ Whiteley says.

“Sergeant looks at b.o., rubs hands on thighs. ‘Mac—’ he says and bogs down again. Whiteley leans to look-see himself.

“ ‘Mac—’ bogs himself; then: ‘Beath. Call him MacBeath.’

“ ‘A’m ca’d MacWyrglinchbeath,’ newcomer says.

“ ‘Sir,’ sergeant prompts.

“ ‘Sir-r,’ newcomer says.

“ ‘Oh,’ Whiteley says, ‘Magillinbeath. Put it down, sergeant.’ Sergeant takes up pen, writes M-a-c with flourish, then stops, handmaking concentric circles with pen above page while owner tries for a peep at b. o. in Whiteley’s hands. ‘Rating, three ack emma,’ Whiteley says. ‘Put that down, sergeant.’

“ ‘Very good, sir,’ sergeant says. Flourishes grow richer, like sustained cavalry threat; leans yet nearer Whiteley’s shoulder, beginning to sweat.

“Whiteley looks up, says, ‘Eh?’ sharply. ‘What’s matter?’ he says.

“ ‘The nyme, sir,’ sergeant says. ‘I can’t get—’

“Whiteley lays b. o. on table; they look at it. ‘People at Wing never could write,’ Whiteley says in fretted voice.

“ ‘‘Tain’t that, sir,’ sergeant says. “Is people just ‘aven’t learned to spell. Wot’s yer nyme agyne, my man?’

“ ‘A’m ca’d MacWyrglinchbeath,’ newcomer says.

“ ‘Ah, the devil,’ Whiteley says. ‘Put him down MacBeath and give him to C. Carry on.’

“But newcomer holds ground, polite but firm. ‘A’m ca’d MacWyrglinchbeath,’ he says without heat.

“Whiteley stares at him. Sergeant stares at him. Whiteley takes pen from sergeant, draws record sheet to him. ‘Spell it.’ Newcomer does so as Whiteley writes it down. ‘Pronounce it again, will you?’ Whiteley says. Newcomer does so. ‘Magillinbeath,’ Whiteley says. ‘Try it, sergeant.’

“Sergeant stares at written word. Rubs ear. ‘Mac — wigglin-beech,’ he says. Then, in hushed tone: ‘Blimey.’

“Whiteley sits back. ‘Right,’ he says. ‘We’ve it correctly. Carry on.’

“ ‘Ye ha’ it MacWyrglinchbeath, sir-r?’ newcomer says. ‘A’d no ha’ ma pay gang wrong.’

“That was before he soloed. Before he deserted, of course. Lugging his petrol tins back and forth, a little slower than anyone else, but always at it if you could suit your time to his. And sending his money, less what he smoked — I have seen his face as he watched the men drinking beer in the canteen — back home to the neighbor who was keeping his horse and cow for him.

“He told me about that arrangement too.

When he and the neighbor agreed, it was in emergency; they both believed it would be over and he would be home in three months. That was a year ago. ‘ ‘Twull be a sore sum A’ll be owin’ him for foragin’ thae twa beasties,’ he told me. Then he quit shaking his head. He became quite still for a while; you could almost watch his mind ticking over. ‘Aweel,’ he says at last, ‘A doot not thae beasts wull ha’ increased in value, too, wi’ thae har-rd times.’

“In those days, you know, the Hun came over your aerodrome and shot at you while you ran and got into holes they had already dug for that purpose, while the Hun sat overhead and dared you to come out.

“So we could see fighting from the mess windows; we were carting off the refuse ourselves then. One day it crashed not two hundred yards away. When we got there, they