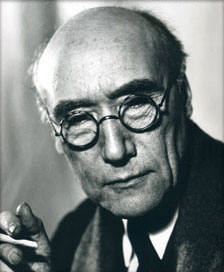

André Paul Guillaume Gide (French: [ɑ̃dʁe pɔl ɡijom ʒid]; 22 November 1869 – 19 February 1951) was a French author whose writings spanned a wide variety of styles and topics. He was awarded the 1947 Nobel Prize in Literature. Gide’s career ranged from his beginnings in the symbolist movement, to criticising imperialism between the two World Wars. The author of more than fifty books, he was described in his obituary in The New York Times as “France’s greatest contemporary man of letters” and “judged the greatest French writer of this century by the literary cognoscenti.”

Known for his fiction as well as his autobiographical works, Gide expressed the conflict and eventual reconciliation of the two sides of his personality (characterized by a Protestant austerity and a transgressive sexual adventurousness, respectively). He suggested that a strict and moralistic education had helped set these facets at odds. Gide’s work can be seen as an investigation of freedom and empowerment in the face of moralistic and puritanical constraints. He worked to achieve intellectual honesty. As a self-professed pederast, he used his writing to explore his struggle to be fully oneself, including owning one’s sexual nature, without betraying one’s values. His political activity was shaped by the same ethos. While sympathetic to Communism in the early 1930s, as were many intellectuals, after his 1936 journey to the USSR he supported the anti-Stalinist left; during the 1940s he shifted towards more traditional values and repudiated Communism as an idea that breaks with the traditions of the Christian civilization.

Early life

Gide was born in Paris on 22 November 1869 into a middle-class Protestant family. His father Jean Paul Guillaume Gide was a professor of law at University of Paris; he died in 1880, when the boy was eleven years old. His mother was Juliette Maria Rondeaux. His uncle was political economist Charles Gide. His paternal family traced its roots to Italy. The ancestral Guidos had moved to France and other western and northern European countries after converting to Protestantism during the 16th century, and facing persecution in Catholic Italy.

Gide was brought up in isolated conditions in Normandy. He became a prolific writer at an early age, publishing his first novel The Notebooks of André Walter (French: Les Cahiers d’André Walter), in 1891, at the age of twenty-one.

In 1893 and 1894, Gide traveled in Northern Africa. There he came to accept his attraction to boys and youths.

Gide befriended Irish playwright Oscar Wilde in Paris, where the latter was in exile. In 1895 the two men met in Algiers. Wilde had the impression that he had introduced Gide to homosexuality, but Gide had discovered homosexuality on his own.

The middle years

In 1895, after his mother’s death, Gide married his cousin Madeleine Rondeaux, but the marriage remained unconsummated. In 1896, he was elected mayor of La Roque-Baignard, a commune in Normandy.

In 1901, Gide rented the property Maderia in St. Brélade’s Bay and lived there while residing on the island of Jersey. This period, 1901–07, is commonly seen as a time of apathy and turmoil for him.

In 1908, Gide helped found the literary magazine Nouvelle Revue Française (The New French Review).

During World War I, Gide visited England. One of his friends there was artist William Rothenstein. Rothenstein described Gide’s visit to his Gloucestershire home in his autobiography:

André Gide was in England during the war…He came to stay with us for a time, and brought with him a young nephew, whose English was better than his own. The boy made friends with my son John, while Gide and I discussed everything under the sun. Once again I delighted in the range and subtlety of a Frenchman’s intelligence; and I regretted my long severance from France. Nobody understood art more profoundly than Gide, no one’s view of life was more penetrating. …

Gide had a half satanic, half monk-like mien; he put one in mind of portraits of Baudelaire. Withal there was something exotic about him. He would appear in a red waistcoat, black velvet jacket and beige-coloured trousers and, in lieu of collar and tie, a loosely knotted scarf. …

The heart of man held no secrets for Gide. There was little that he didn’t understand, or discuss. He suffered, as I did, from the banishment of truth, one of the distressing symptoms of war. The Germans were not all black, and the Allies all white, for Gide.

In 1916, Gide was about 47 years old when he took Marc Allégret, age 15, as a lover. Marc was one of five children of Élie Allégret and his wife. Gide had become friends with the senior Allégret during his own school years when Gide’s mother had hired Allégret as a tutor for her son. Élie Allégret had been best man at Gide’s wedding. After Gide fled with Marc to London, his wife Madeleine burned all his correspondence in retaliation– “the best part of myself,” Gide later commented.

In 1918, Gide met and befriended Dorothy Bussy; they were friends for more than 30 years, and she translated many of his works into English.

Gide also became close friends with the critic Charles Du Bos.Together they were part of the Foyer Franco-Belge, in which capacity they worked to find employment, food and housing for Franco-Belgian refugees who arrived in Paris following the 1914 German invasion of Belgium. Their friendship later declined, due to Du Bos’s perception that Gide had disavowed or betrayed his spiritual faith, in contrast to Du Bos’s own return to faith.

Du Bos’s essay Dialogue avec André Gide was published in 1929. The essay, informed by Du Bos’s Catholic convictions, condemned Gide’s homosexuality. Gide and Du Bos’s mutual friend Ernst Robert Curtius criticised the book in a letter to Gide, writing that “he [Du Bos] judges you according to Catholic morals suffices to neglect his complete indictment. It can only touch those who think like him and are convinced in advance. He has abdicated his intellectual liberty.”

In the 1920s, Gide became an inspiration for such writers as Albert Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre. In 1923, he published a book on Fyodor Dostoyevsky. When he defended homosexuality in the public edition of Corydon (1924), he received widespread condemnation. He later considered this his most important work.

In 1923, Gide sired a daughter, Catherine, by Elisabeth van Rysselberghe, a much younger woman. He had known her for a long time, as she was the daughter of his friends Maria Monnom and Théo van Rysselberghe, a Belgian neo-impressionist painter. This caused the only crisis in the long-standing relationship between Allégret and Gide, and damaged his friendship with van Rysselberghe. This was possibly Gide’s only sexual relationship with a woman, and it was brief in the extreme. Catherine was his only descendant by blood. He liked to call Elisabeth “La Dame Blanche” (“The White Lady”).

Elisabeth eventually left her husband to move to Paris and manage the practical aspects of Gide’s life (they had adjoining apartments built on the rue Vavin). She worshipped him, but evidently they no longer had a sexual relationship.

In 1924, he published an autobiography If it Die… (French: Si le grain ne meurt). In the same year, he produced the first French-language editions of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness and Lord Jim.

After 1925, Gide began to campaign for more humane conditions for convicted criminals. His legal wife, Madeleine Gide, died in 1938. Later he explored their unconsummated marriage in Et nunc manet in te, his memoir of Madeleine, published in English in the United States in 1952.

Africa

From July 1926 to May 1927, Gide traveled through the colony of French Equatorial Africa with his lover Marc Allégret. They went successively to Middle Congo (now the Republic of the Congo), Ubangi-Shari (now the Central African Republic), briefly to Chad and then to Cameroon. He kept a journal, which he published as Travels in the Congo (French: Voyage au Congo) and Return from Chad (French: Retour du Tchad).

In this work, he criticized the behavior of French business interests in the Congo and inspired reform. In particular, he strongly criticized the Large Concessions regime (French: Régime des Grandes Concessions). The government had conceded part of the colony to French companies, allowing them to exploit the area’s natural resources, in particular rubber. He related that native workers were forced to leave their village for several weeks to collect rubber in the forest, and compared their exploitation by the companies to slavery. The book contributed to the growing anti-colonialism movements in France and helped thinkers to re-evaluate the effects of colonialism in Africa.

Political views and the Soviet Union

During the 1930s, Gide briefly became a Communist, or more precisely, a fellow traveler (he never formally joined any Communist party), but he, an individualist himself, advocated the idea of Communist individualism. Despite supporting the Soviet Union, he acknowledged the political repression in the USSR. Gide insisted on the release of Victor Serge, a Soviet writer and a member of the Left Opposition who was prosecuted by the Stalinist regime for his views. As a distinguished writer sympathizing with the cause of Communism, he was invited to speak at Maxim Gorky’s funeral and to tour the Soviet Union as a guest of the Soviet Union of Writers. He encountered censorship of his speeches and was particularly disillusioned with the state of culture under Soviet Communism. In his work, Retour de L’U.R.S.S. (Return from the USSR, 1936), he broke with such socialist friends as Jean-Paul Sartre[citation needed]; the book was addressed to pro-Soviet readers, so the purpose was to expose a reader to doubts instead of presenting harsh criticism. While admitting the economic and social achievements of the USSR compared to the Russian Empire, he noted the decay of culture, the erasure of the individuality of Soviet citizens, and the suppression of any dissent:

Then would it not be better to, instead of playing on words, simply to acknowledge that the revolutionary spirit (or even simply the critical spirit) is no longer the correct thing, that it is not wanted any more? What is wanted now is compliance, conformism. What is desired and demanded is approval of all that is done in the U. S. S. R.; and an attempt is being made to obtain an approval that is not mere resignation, but a sincere, an enthusiastic approval. What is most astounding is that this attempt is successful. On the other hand the smallest protest, the least criticism, is liable to the severest penalties, and in fact is immediately stifled. And I doubt whether in any other country in the world, even Hitler’s Germany, thought to be less free, more bowed down, more fearful (terrorized), more vassalized.

— André Gide Return from the U. S. S. R.

Gide does not express his attitude towards Stalin, but he describes the signs of his personality cult: “in each home, … the same portrait of Stalin, and nothing else”; “portrait of Stalin… , in the same place no doubt where the icon used to be. Is it adoration, love, or fear? I do not know; always and everywhere he is present.” However, Gide wrote that these problems could be solved by raising the cultural level of Soviet society.

When Gide began preparing his manuscript for publication, the Kremlin was immediately informed about it, and the soon Gide would be visited by the Soviet author Ilya Ehrenburg, who said that he agreed with Gide, but asked to postpone the publication, as the Soviet Union assisted the Republicans in Spain; two days later, Louis Aragon delivered a letter from Jef Last asking to postpone the publication. These measures didn’t help, and as the book was published, Gide was condemned in the Soviet press and by the “friends of the USSR”: Nordahl Grieg wrote that the reason of writing the book was Gide’s impatience, and that with his book he made a favour to the Fascists, who greeted it with joy. In 1937, in response, Gide published Afterthoughts on the U. S. S. R.; earlier, Gide read Trotsky’s The Revolution Betrayed and met Victor Serge who provided him more information about the Soviet Union.

In Afterthoughts, Gide is more direct in his criticism of the Soviet society: “Citrine, Trotsky, Mercier, Yvon, Victor Serge, Leguay, Rudolf and many others have helped me with their documentation. Everything they have taught me so far I had only suspected it – has confirmed and reinforced my fears”. The main points of Afterthoughts were that the dictatorship of the proletariat became the dictatorship of Stalin, and that the privileged bureaucracy became the new ruling class which profited by the workers’ surplus labour, spending the state budget on projects like the Palace of Soviets or to raise its own standards of living, while the working class lived in extreme poverty; Gide cited the official Soviet newspapers to prove his statements.

During the World War II Gide came to a conclusion that “absolute liberty destroys the individual and also society unless it be closely linked to tradition and discipline”; he rejected the revolutionary idea of Communism as breaking with the traditions, and wrote that “if civilization depended solely on those who initiated revolutionary theories, then it would perish, since culture needs for its survival a continuous and developing tradition.” In Thesee, written in 1946, he showed that an individual may safely leave the Maze only if “he had clung tightly to the thread which linked him with the past”. In 1947, he said that although during the human history the civilizations rose up and died, the Christian civilization may be saved from doom “if we accepted the responsibility of the sacred charge laid on us by our traditions and our past.” He also said that he remained an individualist and protested against “the submersion of individual responsibility in organized authority, in that escape from freedom which is characteristic of our age.”

Gide contributed to the 1949 anthology The God That Failed. He could not write an essay because of his state of health, so the text was written by Enid Starkie, based on paraphrases of Return from the USSR, Afterthoughts, from a discussion held in Paris at l’Union pour la Verite in 1935, and from his Journal; the text was approved by Gide.

1930s and 1940s

In 1930 Gide published a book about the Blanche Monnier case titled La Séquestrée de Poitiers, changing little but the names of the protagonists. Monnier was a young woman who was kept captive by her own mother for more than 25 years.

In 1939, Gide became the first living author to be published in the prestigious Bibliothèque de la Pléiade.

He left France for Africa in 1942 and lived in Tunis from December 1942 until it was re-taken by French, British and American forces in May 1943 and he was able to travel to Algiers where he stayed until the end of World War II. In 1947, he received the Nobel Prize in Literature “for his comprehensive and artistically significant writings, in which human problems and conditions have been presented with a fearless love of truth and keen psychological insight”. He devoted much of his last years to publishing his Journal. Gide died in Paris on 19 February 1951. The Roman Catholic Church placed his works on the Index of Forbidden Books in 1952.

Gide’s life as a writer

Gide’s biographer Alan Sheridan summed up Gide’s life as a writer and an intellectual:

Gide was, by general consent, one of the dozen most important writers of the 20th century. Moreover, no writer of such stature had led such an interesting life, a life accessibly interesting to us as readers of his autobiographical writings, his journal, his voluminous correspondence and the testimony of others. It was the life of a man engaging not only in the business of artistic creation, but reflecting on that process in his journal, reading that work to his friends and discussing it with them; a man who knew and corresponded with all the major literary figures of his own country and with many in Germany and England; who found daily nourishment in the Latin, French, English and German classics, and, for much of his life, in the Bible; [who enjoyed playing Chopin and other classic works on the piano;] and who engaged in commenting on the moral, political and sexual questions of the day.

“Gide’s fame rested ultimately, of course, on his literary works. But, unlike many writers, he was no recluse: he had a need of friendship and a genius for sustaining it.” But his “capacity for love was not confined to his friends: it spilled over into a concern for others less fortunate than himself.”

Writings

André Gide’s writings spanned many genres – “As a master of prose narrative, occasional dramatist and translator, literary critic, letter writer, essayist, and diarist, André Gide provided twentieth-century French literature with one of its most intriguing examples of the man of letters.”

But as Gide’s biographer Alan Sheridan points out, “It is the fiction that lies at the summit of Gide’s work.” “Here, as in the oeuvre as a whole, what strikes one first is the variety. Here, too, we see Gide’s curiosity, his youthfulness, at work: a refusal to mine only one seam, to repeat successful formulas…The fiction spans the early years of Symbolism, to the “comic, more inventive, even fantastic” pieces, to the later “serious, heavily autobiographical, first-person narratives”…In France Gide was considered a great stylist in the classical sense, “with his clear, succinct, spare, deliberately, subtly phrased sentences.”

Gide’s surviving letters run into the thousands. But it is the Journal that Sheridan calls “the pre-eminently Gidean mode of expression.” “His first novel emerged from Gide’s own journal, and many of the first-person narratives read more or less like journals. In Les faux-monnayeurs, Edouard’s journal provides an alternative voice to the narrator’s.” “In 1946, when Pierre Herbert asked Gide which of his books he would choose if only one were to survive,” Gide replied, ‘I think it would be my Journal.'” Beginning at the age of 18 or 19, Gide kept a journal all of his life and when these were first made available to the public, they ran to 1,300 pages.

Struggle for values

“Each volume that Gide wrote was intended to challenge itself, what had preceded it, and what could conceivably follow it. This characteristic, according to Daniel Moutote in his Cahiers de André Gide essay, is what makes Gide’s work ‘essentially modern’: the ‘perpetual renewal of the values by which one lives.'” Gide wrote in his Journal in 1930: “The only drama that really interests me and that I should always be willing to depict anew, is the debate of the individual with whatever keeps him from being authentic, with whatever is opposed to his integrity, to his integration. Most often the obstacle is within him. And all the rest is merely accidental.”

As a whole, “The works of André Gide reveal his passionate revolt against the restraints and conventions inherited from 19th-century France. He sought to uncover the authentic self beneath its contradictory masks.”

Sexuality

In his journal, Gide distinguishes between adult-attracted “sodomites” and boy-loving “pederasts”, categorizing himself as the latter.

I call a pederast the man who, as the word indicates, falls in love with young boys. I call a sodomite (“The word is sodomite, sir,” said Verlaine to the judge who asked him if it were true that he was a sodomist) the man whose desire is addressed to mature men…The pederasts, of whom I am one (why cannot I say this quite simply, without your immediately claiming to see a brag in my confession?), are much rarer, and the sodomites much more numerous, than I first thought…That such loves can spring up, that such relationships can be formed, it is not enough for me to say that this is natural; I maintain that it is good; each of the two finds exaltation, protection, a challenge in them; and I wonder whether it is for the youth or the elder man that they are more profitable.

Gide’s journal documents his behavior in the company of Oscar Wilde.

Wilde took a key out of his pocket and showed me into a tiny apartment of two rooms…The youths followed him, each of them wrapped in a burnous that hid his face. Then the guide left us and Wilde sent me into the further room with little Mohammed and shut himself up in the other with the other boy. Every time since then that I have sought after pleasure, it is the memory of that night I have pursued…My joy was unbounded, and I cannot imagine it greater, even if love had been added. How should there have been any question of love? How should I have allowed desire to dispose of my heart? No scruple clouded my pleasure and no remorse followed it. But what name then am I to give the rapture I felt as I clasped in my naked arms that perfect little body, so wild, so ardent, so sombrely lascivious? For a long time after Mohammed had left me, I remained in a state of passionate jubilation, and though I had already achieved pleasure five times with him, I renewed my ecstasy again and again, and when I got back to my room in the hotel, I prolonged its echoes until morning.

Gide’s novel Corydon, which he considered his most important work, includes a defense of pederasty. At that time, the age of consent for any type of sexual activity was set at 13.

Bibliography

Novels, novellas, stories

Les cahiers d’André Walter – (The Notebooks of André Walter) – 1891 – A semi-autobiographical novel (written in the form of a journal) that explores Gide’s teen years and his relationships with his cousin Madeleine (“Emmanuèle” in the novel) and his mother.

Le voyage d’Urien – (The Voyage of Urien) – 1893 – The title is “clearly a pun on voyage du rien, meaning voyage of/into nothing.” A Symbolist novella – Urien and his companions set sail on the fabulous ship Orion to mythological lands, to the stagnant sea of boredom, and to the icy sea.

Paludes – (Marshlands) – 1895 – “A satire of literary Paris in general, the world of the salons and cénacles, and, in particular, of the group of more-or-less Symbolist young writers who frequented Mallarmé’s salon.”

El Hadj – 1896 – A tale of nineteen pages in the French edition and subtitled “The Treatise of the False Prophet,” the narrator (El Hadj) tells of a prince who sets out on a journey with the men of his city. After the prince dies, El Hadj conceals the truth and, forced to become a prophet, he leads the men home.

Le Prométhée mal enchaîné – (Prometheus Ill-Bound) – 1899 – A light-hearted satiric novella in which Prometheus leaves his mountain, enters a Paris cafe, and converses with other mythical figures and the waiter about the eagle eating his liver.

L’immoraliste – (The Immoralist) – 1902 – The story of a man, Michel, who travels through Europe and North Africa, attempting to transcend the limitations of conventional morality by surrendering to his appetites (including his attraction to young Arab boys), while neglecting his wife Marceline.

Le retour de l’enfant prodigue – (The Return of the Prodigal Son) – 1907 – Begins almost where the parable in Chapter 15 of the Gospel of Luke ends. – But with Gide’s insight into character, the prodigal son does not simply return when he is destitute: he is also “tired of caprice” and “disenchanted with himself.” – He has stripped himself bare in a reaction against the suffocating luxury of his father’s house.

La porte étroite – (Strait Is the Gate) – 1909 – The title comes from Matthew 7:13-14: “Strait is the gate, and narrow is the way, which leadeth unto life, and few there be that find it.” Set in the Protestant upper-middle-class world of Normandy in the 1880s and reflecting Gide’s own relationship with his cousin Madeleine, Jerome loves his cousin Alissa, but fails to find happiness.

Isabelle – 1911 – The tale of a young man whose studies take him to the remote country home of an eccentric family, where he falls in love with a portrait of their absent daughter. As he unravels the mystery of her absence, he is forced to abandon his passionate ideal. Published with The Pastoral Symphony in Two Symphonies by Vintage Books.

Les Caves du Vatican – (translated as Lafcadio’s Adventures or The Vatican Cellars) – 1914 – Divided into five sections, each named after a character, this farcical story “wanders through numerous capitals of Europe, and involves saints, adventurers, pickpockets…” and centers on the character Lafcadio Wluiki, an adolescent boy who kills a stranger for no reason except personal curiosity about the nature of morality. The plot also involves a gang of French confidence-men who pose as Catholic priests and scam wealthy Catholics by telling them that the Pope has been captured by Freemasons and replaced with an impostor, and that large sums of money are needed in order to rescue the real Pope.

La Symphonie Pastorale – (The Pastoral Symphony) – 1919 – A story of the illicit love between a pastor and the blind orphan whom he rescues from poverty and raises in his own home. His attempt to shield her from the knowledge of evil ends in tragedy. Published with Isabelle in Two Symphonies by Vintage Books.

Les faux-monnayeurs – (The Counterfeiters) – 1925 – An honest treatment of homosexuality and the collapse of morality in middle-class France. As a young writer Edouard attempts to write a novel called Les Faux Monnayeurs, he and his friends Olivier and Bernard pursue a search for knowledge in themselves and their relationships.

L’école des femmes – (The School for Wives) – 1929

Robert – 1930

Geneviève – 1936

(Three novellas later published in one volume.)

A tripartite and delicate dissection of a marriage, as evidenced through the journals of a man, his wife and their daughter. In The School for Wives, it is Eveline’s narrative, from the first elation of her love for Robert, a love which finds no flaw and only self-effacement before the assured superiority of her husband. And then later the recognition of his many weaknesses, the desire to leave him – and concomitantly the Catholic faith. In turn it is Robert’s story, in part a justification, in part an expression of his love for his wife, and of the growing religious belief which coincides with Eveline’s rejection of hers. And lastly their daughter Genevieve recalls an incident in her youth, in no way connected with the drama played out between her parents…. Overall, a not always integrated… examination of moral and religious unrest…

Thésée – (Theseus) – 1946 – The mythical hero of Athens, now elderly, narrates his life story from his carefree youth to his killing of the Minotaur.

La Ramier – – 2002 – Published posthumously by his daughter. Describes a wild erotic night between Gide and a young man named Ferdinand based on an actual encounter the author had.

Poetical and lyrical works

Les poésies d’André Walter – (The Poems of André Walter) – 1892 – A sequence of twenty poems, originally published under the pseudonym of the hero of Gide’s first novel.

La tentative amoureuse, ou le traité du vain désir – (The Attempt at Love, or The Treatise of Vain Desire) – 1893 – The story of two lovers, Luc and Rachel – The course of their love follows the four seasons, “coming to birth in spring, maturing in the summer and dying in the autumn; by the winter, it is dead and the two young people separate.”

Les nourritures terrestres – 1897 (literally meaning “Earthly Food” and translated as The Fruits of the Earth) – “A work of mixed forms: verse, prose poem, travelogue, memoir and dialogue…In the first part, Gide describes his visits to southern Italy, a farm in Normandy, and various locales in North Africa. The persistent theme is living in the present and soaking up sensations and experiences, whether pleasant or unpleasant… The second part, written when Gide was in his sixties, is an endorsement of his youthful philosophy, as well as a broader comment on its religious and political context.”

L’offrande lyrique – (Lyrical Offering) – 1913 – A French translation of the English version of The Gitanjali by the Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore.

Les nouvelles nourritures – 1935 – “A reprise of certain of the major themes of the first Nourritures. (Gide regretted its publication).”

Plays

Philoctète – (Philoctetes) – 1899 – Broadly borrowed from the play by Sophocles. Philoctetes was left behind by Odysseus and his men after his wound from a snake bite began to stink. Now, ten years later, Odysseus returns to the deserted island where they left Philoctetes, to retrieve Heracles’ bow and arrows.

Le roi Candaule – (King Candaules) – 1901 – Taken from stories in Herodotus and Plato, the Lydian King Candaules believes his wife to be the most beautiful woman and wishes to show her off to the humble fisherman Gyges.

Saül – 1903 – A tragedy that shows the “downfall of a king who loses the favor of his Lord and is made a prey of evil spirits.”

Bethsabé – (Bathsheba) – 1912 – An unfinished, lesser play, consisting of three monologues spoken by David on his infatuation for Bathsheba, Uriah’s wife.

Œdipe – (Oedipus) – 1931 – A retelling of the play by Sophocles, written at a time when Gide was breaking free of his own Oedipal complex and realizing that “his years of exalted conjugal devotion were no more than the recapitulation of his infantile desire for exclusive possession of his mother.”

Perséphone – 1943 – Based on an earlier unfinished series of poems Proserpine and retitled Perséphone. “A dramatic poem in the Symbolist manner on the Persephone myth, presented as an opera-ballet, with music by Igor Stravinsky and choreography by Kurt Jooss.”

Le retour – (The Return) – 1946 – An unfinished libretto for a projected opera with Raymond Bonheur on the story of The Prodigal Son. Gide wrote this in 1900, and it was published in book form in France in 1946.

Le procès – (The Process) – 1947 – Co-written with Jean-Louis Barrault, this play is drawn from Kafka’s novel Der Prozess (The Trial).

Autobiographical works

Si le grain ne meurt – (translated as If It Die) – 1926 – (The original title means “Unless the grain dies,” and comes from John 12:24: “Except a corn of wheat fall into the ground and die, it abideth alone: but if it die, it bringeth forth much fruit.”) – Gide’s autobiography of his childhood and youth, ending with the death of his mother in 1895.

Et Nunc Manet in Te – – (translated as Madeleine) – 1951 – (The original title comes from a quote of the Roman poet Virgil – referring to Orpheus and his lost wife Eurydice – meaning “And now she remains in you.”) Gide’s memoir of his wife Madeleine and their complex relationship and unconsummated marriage. While she was alive, Gide had excluded all references to his wife in his writings. This was published after her death.

Journals, 1889–1949 – Published in four volumes – translated and edited by Justin O’Brien – Also available in an abridged two-volume edition. “Beginning with a single entry for the year 1889, when he was twenty, and continuing throughout his life, the Journals of André Gide constitute an enlightening, moving, and endlessly fascinating chronicle of creative energy and conviction.”

Ainsi-soit-il, ou: Les jeux sont faits – (So Be It, or The Chips Are Down) – 1952 – Gide’s final memoirs, published posthumously.

Travel writings

Amyntas – (North African Journals) – 1906 – (translated into English by Richard Howard under the same title.) Contains four parts: Mopsus, Wayside Pages (Feuilles de Route), Biskra to Touggourt; and Travel Foregone (Le Renoncement au Voyage). The title alludes to Virgil’s Eclogues, in which Amyntas and Mopsus (the title of Gide’s first sketch) are the names of graceful shepherds. Written between 1899 and 1904, these journals recall Gide’s journey to North Africa, scene of his first significant encounter with a beloved Arab boy. The exotic country of North Africa enraptures Gide – the enchantment of the souk, the narrow odorous streets, the hashish dens, the glowing colors of sky, the desert itself.

La marche Turque – (Journey to Turkey) – 1914 – Hastily written notes on Gide’s trip to Turkey.

Voyage au Congo – (Travels in the Congo) – 1927

Le retour de Tchad – (The Return from Chad) – 1928

On his return in 1927 from an extensive tour of French Equatorial Africa, Gide published these two travel notebooks. Among other things his report contained a documented account of the inhuman treatment of African laborers by the companies that held exploiting concessions in the colonies. This indictment had obviously political overtones which tended to make Gide the ally of the anti-colonialist, anti-capitalist left.

Retour de l’U. R. S. S. – (Return from the U.S.S.R.) – 1936 – Not a true travel book (there are no dates or chronology), but rather Gide’s assessment of Soviet society, progressing from delighted approval to bitter criticism.

Retouches â mon retour de l’U. R. S. S. – (Afterthoughts: A Sequel to Return from the U.S.S.R.) – 1937

A Naples – Reconnaissance à l’Italie – (To Naples – A Trip to Italy) – 1937 – Published posthumously.

Gide agreed to contribute to a collection of essays in which notable intellectuals would describe their conversion to and disillusionment with Communism. When his health prevented him from authoring such an essay, Enid Starkie, at the editor’s request and under Gide’s direction, crafted an essay from his two publications from the 1930s. It appeared in The God That Failed (1949).

Philosophical and religious writings

Corydon – 1920 – Four Socratic-style dialogues that explore the nature of homosexuality and its place in society. The title comes from the name of a shepherd who loved boys in Virgil’s Eclogues.

Numquid et tu . . .? – 1922 – (The title comes from a quote from the book of John (7:47-52) that means “Are you also [deceived]?”) Gide’s notebook which documents his religious quest, much of it consisting of his comments on Biblical quotations, often comparing the Latin and French translations.

Un esprit non prevenu – (An Unprejudiced Mind) – 1929

Criticism on literature, art and music

Le traité du Narcisse: Theorie du symbole – (The Treatise of Narcissus: Theory of the Symbol) – 1891 – A work on Symbolism, Gide begins with the myth of Narcissus, then explores the meaning of the Symbol and the truth behind it.

Réflexions sur quelques points de littérature – (Reflections on Some Points of Literature) – 1897

Lettres à Angèle – (Letters to Angèle) – 1900 – Angèle was the name of the cultivated literary hostess in Gide’s novel Paludes. These letters are short essays on literary topics originally published in the literary review L’Ermitage and later collected in book form.

De l’influence en littérature – (On Influence in Literature) – 1900 – The text of a lecture Gide gave to Libre Esthétique (a Brussels literary society), and later published in the journal L’Ermitage. A praise of influence – only weaker artists fear the influence of other minds – the strong artist embraces it.

Les limites de l’art – (The Limits of Art) – 1901

De l’importance du public – (The Importance of the Public) – 1903 – Gide discusses his movement away from Symbolism and “Art for Art’s Sake” towards the need to communicate with a wider public.

Oscar Wilde – (Oscar Wilde: A Study) – 1910

Dostoïevsky – 1923

Le journal des faux-monnayeurs – (The Journal for The Counterfeiters) – 1926 – Gide’s working notes for his novel The Counterfeiters, in the form of a journal.

Essai sur Montaigne – (Living Thoughts of Montaigne) – 1929

Découvrons Henri Michaux – (Discovering Henri Michaux) – 1941 – The text of a talk Gide gave to a literary society on his friend, the Belgian poet Henri Michaux.

Paul Valéry – 1947

Notes sur Chopin – 1948 – Reflecting Gide’s love of Chopin, this work urges the pianist who plays Chopin to seek, invent, improvise, and gradually discover the composer’s thoughts.

Anthologie de la poésie française – 1949 – Anthology of French poets, edited by Gide.

Collections of essays and lectures

Prétextes (Pretexts: Reflections on Literature and Morality) – 1903

Nouveaux prétextes – 1911

Morceaux choisis – 1921

Incidences – 1924

Ne jugez pas – (Judge Not) – 1931 – A collection of three previously published essays with legal themes – Souvenirs de la Cour d’assises (Recollections on the Assize Court); L’Affaire Redureau; (The Redurou Affair) and La séquestrée de Poitiers. (The Prisoner of Poitiers)

Littérature engagée – 1950 – A collection of Gide’s political articles and speeches.