In 1925 four sketches from the developing work were published. “Here Comes Everybody” was published as “From Work in Progress” in the Contact Collection of Contemporary Writers, edited by Robert McAlmon. “The Letter” was published as “Fragment of an Unpublished Work” in Criterion 3.12 (July 1925), and as “A New Unnamed Work” in Two Worlds 1.1. (September 1925). The first published draft of “Anna Livia Plurabelle” appeared in Le Navire d’Argent 1 in October, and the first published draft of “Shem the Penman” appeared in the Autumn–Winter edition of This Quarter.

In 1925-6 Two Worlds began to publish redrafted versions of previously published fragments, starting with “Here Comes Everybody” in December 1925, and then “Anna Livia Plurabelle” (March 1926), “Shem the Penman” (June 1926), and “Mamalujo” (September 1925), all under the title “A New Unnamed Work”.

Eugene Jolas befriended Joyce in 1927, and as a result serially published revised fragments from Part I in his transition literary journal. This began with the debut of the book’s opening chapter, under the title “Opening Pages of a Work in Progress”, in April 1927. By November chapters I.2 through I.8 had all been published in the journal, in their correct sequence, under the title “Continuation of a Work in Progress”. From 1928 Part’s II and III slowly began to emerge in transition, with a brief excerpt of II.2 (“The Triangle”) published in February 1928, and Part III’s four chapters between March 1928 and November 1929.

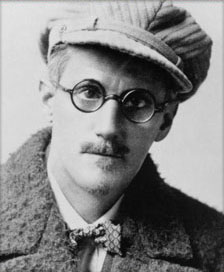

At this point, Joyce started publishing individual chapters from Work in Progress. In 1929, Harry and Caresse Crosby, owners of the Black Sun Press, contacted James Joyce through bookstore owner Sylvia Beach and arranged to print three short fables about the novel’s three children Shem, Shaun and Issy that had already appeared in translation. These were “The Mookse and the Gripes”, “The Triangle”, and “The Ondt and the Gracehoper”. The Black Sun Press named the new book Tales Told of Shem and Shaun for which they paid Joyce US$2,000 for 600 copies, unusually good pay for Joyce at that time. Their printer Roger Lescaret erred when setting the type, leaving the final page with only two lines. Rather than reset the entire book, he suggested to the Crosby’s that they ask Joyce to write an additional eight lines to fill in the remainder of the page. Caresse refused, insisting that a literary master would never alter his work to fix a printer’s error. Lescaret appealed directly to Joyce, who promptly wrote the eight lines requested. The first 100 copies of Joyce’s book were printed on Japanese vellum and signed by the author. It was hand-set in Caslon type and included an abstract portrait of Joyce by Constantin Brâncuși, a pioneer of modernist abstract sculpture. Brâncuși’s drawings of Joyce became among the most popular images of him.

Faber and Faber published book editions of “Anna Livia Plurabelle” (1930), and “Haveth Childers Everywhere” (1931), HCE’s long defence of his life which would eventually close chapter III.3. A year later they published Two Tales of Shem and Shaun, which dropped “The Triangle” from the previous Black Sun Press edition. Part II was published serially in transition between February 1933 and May 1938, and a final individual book publication, Storiella as She Is Syung, was published by Corvinus Press in 1937, made up of sections from what would become chapter II.2.

By 1938 virtually all of Finnegans Wake was in print in the transition serialisation and in the booklets, with the exception of Part IV. Joyce continued to revise all previously published sections until Finnegans Wake’s final published form, resulting in the text existing in a number of different forms, to the point that critics can speak of Finnegans Wake being a different entity to Work in Progress.

The book was finally published simultaneously by Faber and Faber in London and by Viking Press in New York on 4 May 1939, after seventeen years of composition.

In March 2010, a new edition was published by Houyhnhnm Press in conjunction with Penguin. Editors Danis Rose and John O’Hanlon claim to make 9,000 minor “yet crucial” corrections and amendments to what they title The Restored Finnegans Wake. Scholar Tim Conley, however, laments that “The process of the editing remains concealed. Readers are repeatedly told of how much hard and honorable work has gone into the restoration, but the work itself is kept out of view and thus away from judgment.” He praises the 2012 Oxford edition edited by Robbert-Jan Henkes, Erik Bindervoet, and Finn Fordham for its more scholarly editorial apparatus. By turns skeptical and appreciative, he begins and concludes his review essay celebrating the existence of these new textual options.

Despite its linguistic complexity, Finnegans Wake has been translated into French, German, Greek, Japanese, Korean, Latin, Polish, Russian, Serbian, Spanish (by M. Zabaloy), Dutch, Portuguese, Turkish, and Swedish (by B. Falk). Well-advanced translations in progress include Chinese and Italian.

Dramatic and musical adaptions

Thornton Wilder’s play The Skin of Our Teeth (1942) uses many devices from Finnegans Wake, such as a family that represents the totality of humanity, cyclical storytelling, and copious Biblical allusions. A musical play, The Coach with the Six Insides by Jean Erdman, based on the character Anna Livia Plurabelle, was performed in New York in 1962. Parts of the book were adapted for the stage by Mary Manning as Passages from Finnegans Wake, (1965) which was in turn used as the basis for a film of the novel by Mary Ellen Bute.

In recent years Olwen Fouéré’s solo performance play riverrun, based on the theme of rivers in Finnegans Wake, has received critical accolades around the world. Adam Harvey has also adapted Finnegans Wake for the stage. Martin Pearlman’s three-act Finnegan’s Grand Operoar is for speakers with an instrumental ensemble. A version adapted by Barbara Vann with music by Chris McGlumphy was produced by The Medicine Show Theater in April 2005.

John Cage’s The Wonderful Widow of Eighteen Springs became the first musical setting of words from Finnegans Wake, approved by the Joyce Estate in 1942. He used text taken from page 558. Roaratorio: an Irish circus on Finnegans Wake (1979) combines a collage of sounds mentioned in Finnegans Wake – including farts, guns and thunderclaps – with Irish jigs and Cage reading his text Writing for the Second Time through Finnegans Wake. Cage also set Nowth upon Nacht to music in 1984. In 1947 Samuel Barber set an excerpt from Finnegans Wake as the song Nuvoletta for soprano and piano. He also composed a piece for orchestra in 1971 entitled Fadograph of a Yestern Scene, the title a quote from the first part of the novel.

Luciano Berio set much Joyce, and was an admirer of Finnegans Wake, but only one of his pieces, A-Ronne (1975) directly refers to it (heard in the vocal fragment “run”, derived from “riverrun”). Influenced by Berio, British composer Roger Marsh set selected passages concerned with the character Anna Livia Plurabelle in his 1977 Not a soul but ourselves for amplified voices using extended vocal techniques. Marsh went on to direct the unabridged (29 hour) audiobook of Finnegans Wake issued by Naxos in 2021.

The Japanese composer Toru Takemitsu used several quotes from the novel in his music: its first word for his composition for piano and orchestra, riverrun (1984). His 1980 piano concerto is called Far calls. Coming, far! taken from the last page of Finnegans Wake. Similarly, he entitled his 1981 string quartet A Way a Lone, taken from the last sentence of the work. Other composers from the experimental classical tradition with settings include Fred Lerdahl (Wake, 1967-8), and Tod Machover (Soft Morning, City!, 1980).

André Hodeir composed a jazz cantata on Anna Plurabelle (1966). Scottish group The Wake’s second album is called Here Comes Everybody (1985). Phil Minton set passages of the Wake to music, on his 1998 album Mouthfull of Ecstasy. In 2015 Waywords and Meansigns: Recreating Finnegans Wake [in its whole wholume] set Finnegans Wake to music unabridged, featuring an international group of musicians and Joyce enthusiasts.

In 2000, Danish visual artists Michael Kvium and Christian Lemmerz created a multimedia project called “the Wake”, an eight-hour-long silent movie based on the book. Between 2014–2016 in Poland, many adaptations of Finnegans Wake saw completion, including publication of the text as a musical score, a short film Finnegans Wake//Finneganów tren, a multimedia adaptation First We Feel Then We Fall and K. Bartnicki’s intersemiotic translations into sound and verbovisual. In October 2020, Austrian illustrator Nicolas Mahler presented a small-format (ISO A6) 24-page comic adaptation of Finnegans Wake with reference to comic figures Mutt and Jeff.

In 2011 German band Tangerine Dream released his instrumental album Finnegans Wake, inspired by the novel.

In film

In 1965 American experimental filmmaker Mary Ellen Bute released a film adaptation of Joyce’s novel under the title Passages from Finnegans Wake.

Alberte Pagán’s Eclipse (2010) is inspired by the novel and includes Joyce’s reading of chapter I.8 in its soundtrack.

Cultural impact

Finnegans Wake is a difficult text, and Joyce did not aim it at the general reader. Nevertheless, certain aspects of the work have made an impact on popular culture beyond the awareness of it being difficult.

Similarly, the comparative mythology term monomyth, as described by Joseph Campbell in his book The Hero with a Thousand Faces, was taken from a passage in Finnegans Wake. The work of Marshall McLuhan was inspired by James Joyce; his collage book War and Peace in the Global Village has numerous references to Finnegans Wake.

Esther Greenwood, Sylvia Plath’s protagonist in The Bell Jar, is writing her college thesis on the “twin images” in Finnegans Wake, although she never manages to finish either the book or her thesis.