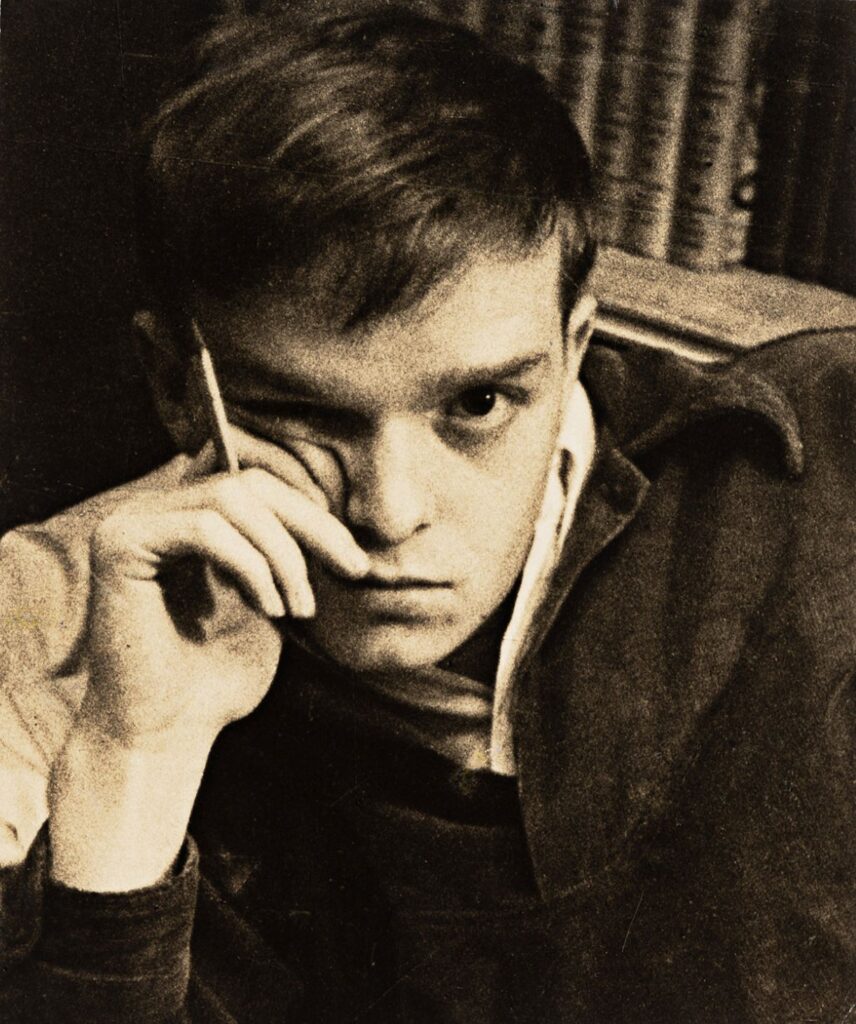

A Day’s Work, Truman Capote

A Day’s Work

SCENE: A RAINY APRIL MORNING, 1979. I am walking along Second Avenue in New York City, carrying an oilcloth shopping satchel bulging with house-cleaning materials that belong to Mary Sanchez, who is beside me trying to keep an umbrella above the pair of us, which is not difficult as she is much taller than I am, a six-footer.

Mary Sanchez is a professional cleaning woman who works by the hour, at five dollars an hour, six days a week. She works approximately nine hours a day, and visits on the average twenty-four different domiciles between Monday and Saturday: generally her customers require her services just once a week.

Mary is fifty-seven years old, a native of a small South Carolina town who has “lived North” the past forty years. Her husband, a Puerto Rican, died last summer.

She has a married daughter who lives in San Diego, and three sons, one of whom is a dentist, one who is serving a ten-year sentence for armed robbery, a third who is “just gone, God knows where.

He called me last Christmas, he sounded far away. I asked where are you, Pete, but he wouldn’t say, so I told him his daddy was dead, and he said good, said that was the best Christmas present I could’ve given him, so I hung up the phone, slam, and I hope he never calls again. Spitting on Dad’s grave that way.

Well, sure, Pedro was never good to the kids. Or me. Just boozed and rolled dice. Ran around with bad women. They found him dead on a bench in Central Park.

Had a mostly empty bottle of Jack Daniel’s in a paper sack propped between his legs; never drank nothing but the best, that man. Still, Pete was way out of line, saying he was glad his father was dead. He owed him the gift of life, didn’t he?

And I owed Pedro something too. If it wasn’t for him, I’d still be an ignorant Baptist, lost to the Lord. But when I got married, I married in the Catholic church, and the Catholic church brought a shine to my life that has never gone out, and never will, not even when I die. I raised my children in the Faith; two of them turned out fine, and I give the church credit for that more than me.”

Mary Sanchez is muscular, but she has a pale round smooth pleasant face with a tiny upturned nose and a beauty mole high on her left cheek. She dislikes the term “black,” racially applied. “I’m not black. I’m brown.

A light-brown colored woman. And I’ll tell you something else. I don’t know many other colored people that like being called blacks. Maybe some of the young people. And those radicals. But not folks my age, or even half as old. Even people who really are black, they don’t like it. What’s wrong with Negroes? I’m a Negro, and a Catholic, and proud to say it.”

I’ve known Mary Sanchez since 1968, and she has worked for me, periodically, all these years. She is conscientious, and takes far more than a casual interest in her clients, many of whom she has scarcely met, or not met at all, for many of them are unmarried working men and women who are not at home when she arrives to clean their apartments; she communicates with them, and they with her, via notes: “Mary, please water the geraniums and feed the cat.

Hope this finds you well. Gloria Scotto.”

Once I suggested to her that I would like to follow her around during the course of a day’s work, and she said well, she didn’t see anything wrong with that, and in fact, would enjoy the company: “This can be kind of lonely work sometimes.”

Which is how we happen to be walking along together on this showery April morning. We’re off to her first job: a Mr. Andrew Trask, who lives on East Seventy-third Street.

TC: What the hell have you got in this sack?

MARY: Here, give it to me. I can’t have you cursing.

TC: No. Sorry. But it’s heavy.

MARY: Maybe it’s the iron.

TC: You iron their clothes? You never iron any of mine.

MARY: Some of these people just have no equipment. That’s why I have to carry so much. I leave notes: get this, get that. But they forget. Seems like all my people are bound up in their troubles. Like this Mr. Trask, where we’re going.

I’ve had him seven, eight months, and I’ve never seen him yet. But he drinks too much, and his wife left him on account of it, and he owes bills everywhere, and if ever I answered his phone, it’s somebody trying to collect. Only now they’ve turned off his phone.

(We arrive at the address, and she produces from a shoulder-satchel a massive metal ring jangling with dozens of keys. The building is a four-story brownstone with a midget elevator.)

TC (after entering and glancing around the Trask establishment—one fair-sized room with greenish arsenic-colored walls, a kitchenette, and a bathroom with a broken, constantly flowing toilet): Hmm. I see what you mean. This guy has problems.

MARY (opening a closet crammed and clammy with sweat-sour laundry): Not a clean sheet in the house! And look at that bed! Mayonnaise! Chocolate! Crumbs, crumbs, chewing gum, cigarette butts. Lipstick! What kind of woman would subject herself to a bed like that? I haven’t been able to change the sheets for weeks. Months.

(She turns on several lamps with awry shades; and while she labors to organize the surrounding disorder, I take more careful note of the premises. Really, it looks as though a burglar had been plundering there, one who had left some drawers of a bureau open, others closed.

There’s a leather-framed photograph on the bureau of a stocky swarthy macho man and a blond hoity-toity Junior League woman and three tow-headed grinning snaggle-toothed suntanned boys, the eldest about fourteen.

There is another unframed picture stuck in a blurry mirror: another blonde, but definitely not Junior League—perhaps a pickup from Maxwell’s Plum; I imagine it is her lipstick on the bed sheets.

A copy of the December issue of True Detective magazine is lying on the floor, and in the bathroom, stacked by the ceaselessly churning toilet, stands a pile of girlie literature—Penthouse, Hustler, Oui; otherwise, there seems to be a total absence of cultural possessions. But there are hundreds of empty vodka bottles everywhere—the miniature kind served by airlines.)

TC: Why do you suppose he drinks only these miniatures?

MARY: Maybe he can’t afford nothing bigger. Just buys what he can. He has a good job, if he can hold on to it, but I guess his family keeps him broke.

TC: What does he do?

MARY: Airplanes.

TC: That explains it. He gets these little bottles free.

MARY: Yeah? How come? He’s not a steward. He’s a pilot.

TC: Oh, my God.

(A telephone rings, a subdued noise, for the instrument is submerged under a rumpled blanket. Scowling, her hands soapy with dishwater, Mary unearths it with the finesse of an archeologist.)

MARY: He must have got connected again. Hello? (Silence) Hello?

A WOMAN’S VOICE: Who is this?

MARY: This is Mr. Trask’s residence.

WOMAN’S VOICE: Mr. Trask’s residence? (Laughter; then, hoity-toity) To whom am I speaking?

MARY: This is Mr. Trask’s maid.

WOMAN’S VOICE: So Mr. Trask has a maid, has he? Well, that’s more than Mrs. Trask has. Will Mr. Trask’s maid please tell Mr. Trask that Mrs. Trask would like to speak to him?

MARY: He’s not home.

MRS. TRASK: Don’t give me that. Put him on.

MARY: I’m sorry, Mrs. Trask. I guess he’s out flying.

MRS. TRASK (bitter mirth): Out flying? He’s always flying, dear. Always.

MARY: What I mean is, he’s at work.

MRS. TRASK: Tell him to call me at my sister’s in New Jersey. Call the instant he comes in, if he knows what’s good for him.

MARY: Yes, ma’am. I’ll leave that message. (She hangs up) Mean woman. No wonder he’s in the condition he’s in. And now he’s out of a job. I wonder if he left me my money. Uh-huh. That’s it. On top of the fridge.

(Amazingly, an hour or so afterward she has managed to somewhat camouflage the chaos and has the room looking not altogether shipshape but reasonably respectable. With a pencil, she scribbles a note and props it against the bureau mirror: “Dear Mr. Trask yr. wive want you fone her at her sistar place sinsirly Mary Sanchez.”

Then she sighs and perches on the edge of the bed and from her satchel takes out a small tin box containing an assortment of roaches; selecting one, she fits it into a roach-holder and lights up, dragging deeply, holding the smoke down in her lungs and closing her eyes. She offers me a toke.)

TC: Thanks. It’s too early.

MARY: It’s never too early. Anyway, you ought to try this stuff. Mucho cojones. I get it from a customer, a real fine Catholic lady; she’s married to a fellow from Peru. His family sends it to them. Sends it right through the mail. I never use it so’s to get high. Just enough to lift the uglies a little. That heaviness. (She sucks on the roach until it all but burns her lips) Andrew Trask. Poor scared devil.

He could end up like Pedro. Dead on a park bench, nobody caring. Not that I didn’t care none for that man. Lately, I find myself remembering the good times with Pedro, and I guess that’s what happens to most people if ever they’ve once loved somebody and lose them; the bad slips away,