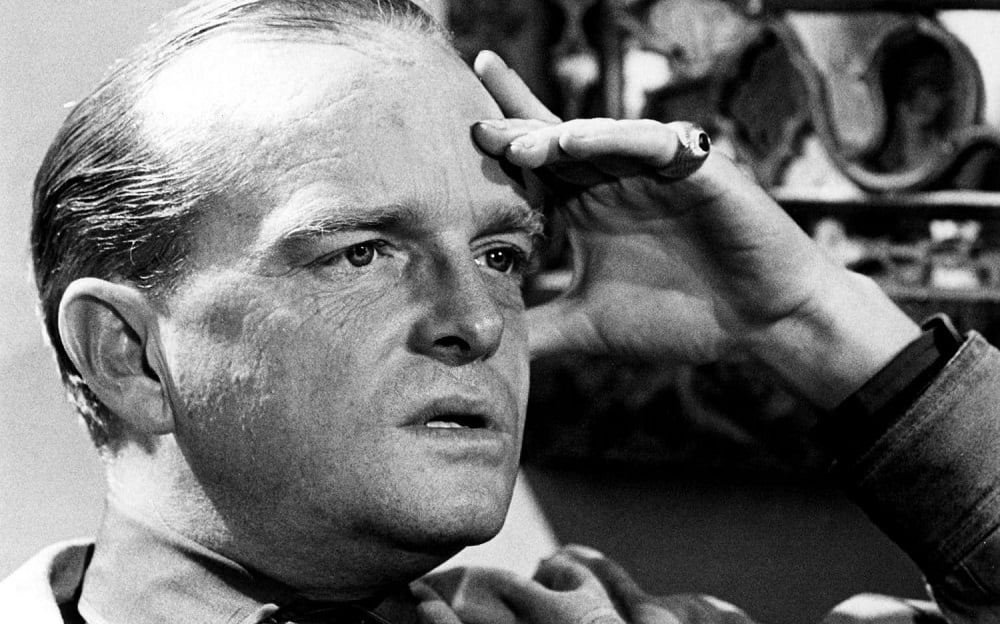

Haiti, Truman Capote

HAITI

To look at, Hyppolite is perhaps an ugly man: monkey-thin, gaunt-faced, quite dark, he looks (through silver schoolmarm spectacles), listens with the steadiest, most gracious precision, his eyes echoing a subtle and basic understanding. One feels with him a certain safety; there is created between you that too uncommon circumstance, no sense of isolation.

This morning I heard that during the night his daughter died, a daughter eight months old; there are other children, he has been married many times, five or six; even so, how hard it must be, for he is not young.

No one has told me, I wonder if there is a wake. In Haiti they are extravagant, these wakes, and excessively stylized: the mourners, strangers in large part, claw air, drum their heads on the ground, in unison moan a low doglike grief. Heard at night, or seen suddenly on a country road, it seems so alien the heart shivers, and then one realizes that in essence these are mimes.

Because he is the most popular of Haiti’s primitive painters, Hyppolite could afford a running-water house, real beds, electricity; as it is, he lives by lamp, by candle, and all the neighbors, old withered coconut-headed ladies and handsome sailor boys and hunched sandal makers, can see into his affairs as he can see into theirs.

Once, some while back, a friend took it upon himself to rent Hyppolite another house, a sturdy sort of place with concrete floors and walls behind which one could hide, but of course he was not happy there, he has no need for secrecy or comfort. It is for this reason that I find Hyppolite admirable, for there is nothing in his art that has been slyly transposed, he is using what lives within himself, and that is his country’s spiritual history, its singings and worships.

Displayed prominently in the room where he paints is an enormous trumpet-shaped shell; pink and elaborately curled, it is like some ocean flower, an underwater rose, and if you blow through it, there comes forth a howl hoarse and lonesome, a windlike sound: it is for sailors a magic horn that calls the wind, and Hyppolite, who plans an around-the-world voyage aboard his own red-sailed ship, practices upon it regularly. Most of his energy and all his money go into the building of this ship; there is about his dedication the quality frequently seen in those who supervise the plotting of their own funerals, the building of their own tombs.

Once he sets sail and is out of land’s sight, I wonder if again anyone will ever see him.

From the terrace where in the mornings I sit reading or writing, I can see the mountains sliding blue and bluer down to the harbor bay. Below there is the whole of Port-au-Prince, a town whose colors are paled into peeling historical pastels by centuries of sun: sky-gray cathedral, hyacinth fountain, green-rust fence. To the left, and like a city within this other, there is a great chalk garden of baroque stone; here is the cemetery, this is where, amid flat metal light and monuments like birdcages, they will bring his daughter: they will bring her up the hill, a dozen of them dressed in straw hats and black, sweet peas heavy on the air.

- Tell me, why are there so many dogs? to whom do they belong, and for what purpose? Mangy, hurt-eyed, they pad along the streets in little herds like persecuted Christians, all innocuous enough by day, but come night how their vanity and their voices exaggerate! First one, another, then all, through the hours you can hear their enraged, embittered, moon-imploring tirades. S. says it is like a reversed alarm clock, for as soon as the dogs commence, and that indeed is early, it is time to go to bed. You might as well; the town has drawn shutters by ten, except, that is, on rahrah weekends, when drums and drunks drown out the dogs. But I like hearing a morning multitude of cock-crows; they set blowing a windfall of reverberations. On the other hand, what is more irritating than the racket of car horns? Haitians who own cars seem so to adore honking their horns; one begins to suspect this activity of political and/or sexual significance.

- If it were possible, I should like to make a film here; except for incidental music it would be soundless, nothing but a camera brilliantly framing architecture, objects. There is a flying kite, on the kite there is a crayon eye, now the eye is loose and blowing in the wind, it snags on a fence and we, the eye, the camera, see a house (like M. Rigaud’s).

This is a tall, brittle, somewhat absurd structure representing no particular period, but seeming rather to be of an infinitely bastard lineage: the French influence, and England in somber Victorian garb; there is an Oriental quality, too, touches that suggest a lantern of frilled paper.

It is a carved house, its turrets, towers, porticoes are laced with angel heads, snowflake shapes, valentine hearts: as the camera traces each of these we hear a tantalizing sub-musical tap-rap of bamboo rods. A window, very sudden; a sugar-white meringue of curtains, and a lumplike eye, and then a face, a woman like an old pressed flower, jet at her throat and jet combs in her hair; we pass through her, and into the room, two green chameleons race over the chifforobe mirror where her image shines. Like dissonant piano notes, the camera shifts with swift sharp jabs, and we are aware of the happenings our eyes never notice: a rose leaf falling, a picture tilting crooked. Now we have begun.

- Comparatively few tourists come to Haiti, and a fair number of those who do, especially the average American couple, sit around in their hotels in a superior sulk. It is unfortunate, for of all the West Indies, Haiti is quite the most interesting; still, when one considers the objectives of these vacationers their attitude is not without reason: the nearest beach is a three-hour drive, night life is unimpressive, there is no restaurant whose menu is very distinguished. Aside from the hotels, there are only a few public places where late of an evening one can go for a rum soda; among the pleasanter of these are the whorehouses set back among the foliage along the Bizonton Road.

All the houses have names, rather egotistical ones: the Paradise, for example. And they are uncompromisingly respectable, perfect parlor decorum is observed: the girls, most of whom are from the Dominican Republic, sit on the front porch rocking in rocking chairs, fanning themselves with cardboard pictures of Jesus and conversing in a gentle, gossipy, laughing way; it is like any American summer scene. Beer, not whiskey or even champagne, is considered de rigueur, and if one wants to make an impression, it is the drink to order.

One girl I know can down thirty bottles; she is older than the others, wears lavender lipstick, is rumba-hipped and viper-tongued, all of which makes her a popular lady indeed, though she herself says she will never feel like a success until she can afford to have every tooth in her head converted into solid gold.

- The Estimé government has passed a law which forbids promenading in the streets sans shoes: this is a hard, uneconomical ruling, and an uncomfortable one as well, especially for those peasants who must bring their produce to market afoot. But the government, now anxious to make the country more of a tourist attraction, feels that shoeless Haitians might depress his potential trade, that the poorness of the people should not be overt. By and large, however, Haitians are poor, but about this poverty there is none of that vicious, mean atmosphere which surrounds the poverty that demands a keeping-up of appearances.

It always makes me rather wretched when some popular platitude proves true; still, it is a fact, I suppose, that the most generous of us are those that have the least to be generous with. Almost any Haitian who comes to call will conclude his visit by presenting you with a small, usually odd gift: a can of sardines, a spool of thread; but these gifts are given with such dignity and tenderness that, ah! the sardines have swallowed pearls, the thread is purest silver.

- This is R.’s story. A few days ago he went out into the country to sketch; suddenly, coming to the bottom of a hill, he saw a tall, slant-eyed, ragged girl. She was tied to the trunk of a tree, wire and rope binding her there. At first, because she laughed at him, he thought it was a joke, but when he tried to let her loose several children appeared and began to poke at him with sticks; he asked them why the girl was tied to the tree, but they giggled and shouted and would not give an answer.

Presently an old man joined them; he was carrying a gourd filled with water. When R. asked again about the girl, the old man, tears misting his eyes, said, “She is bad, monsieur, there is no use she is so bad,” and shook his head. R. started back up the hill; then, turning, he saw the man was letting her drink from the gourd, and as she took a last swallow she spat into his face; with a gentle patience the old man wiped himself and walked away.

- I like Estelle, and I must say I have come to care less for