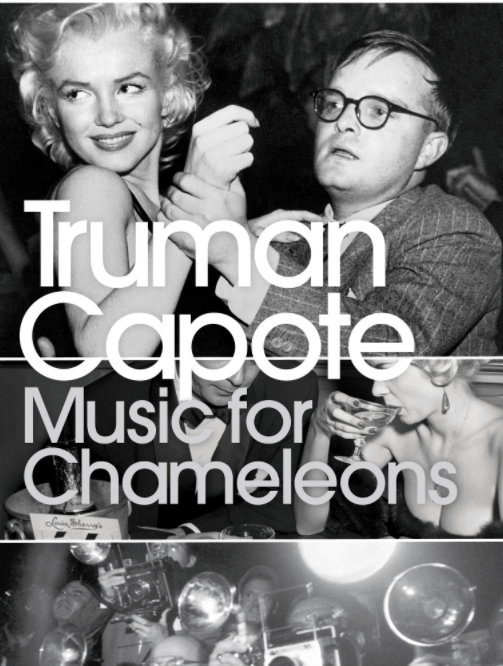

Music for Chameleons, Truman Capote

For Tennessee Williams

CONTENTS

Preface

Part I Music for Chameleons

I Music for Chameleons

II Mr. Jones

III A Lamp in a Window

IV Mojave

V Hospitality

VI Dazzle

Part II Handcarved Coffins

A Nonfiction Account of an American Crime

Part III Conversational Portraits

I A Day’s Work

II Hello, Stranger

III Hidden Gardens

IV Derring-do

V Then It All Came Down

VI A Beautiful Child

VII Nocturnal Turnings

Preface

MY LIFE—AS AN ARTIST, AT least—can be charted as precisely as a fever: the highs and lows, the very definite cycles.

I started writing when I was eight—out of the blue, uninspired by any example. I’d never known anyone who wrote; indeed, I knew few people who read. But the fact was, the only four things that interested me were: reading books, going to the movies, tap dancing, and drawing pictures. Then one day I started writing, not knowing that I had chained myself for life to a noble but merciless master. When God hands you a gift, he also hands you a whip; and the whip is intended solely for self-flagellation.

But of course I didn’t know that. I wrote adventure stories, murder mysteries, comedy skits, tales that had been told me by former slaves and Civil War veterans. It was a lot of fun—at first. It stopped being fun when I discovered the difference between good writing and bad, and then made an even more alarming discovery: the difference between very good writing and true art; it is subtle, but savage. And after that, the whip came down!

As certain young people practice the piano or the violin four and five hours a day, so I played with my papers and pens. Yet I never discussed my writing with anyone; if someone asked what I was up to all those hours, I told them I was doing my school homework. Actually, I never did any homework. My literary tasks kept me fully occupied: my apprenticeship at the altar of technique, craft; the devilish intricacies of paragraphing, punctuation, dialogue placement. Not to mention the grand overall design, the great demanding arc of middle-beginning-end. One had to learn so much, and from so many sources: not only from books, but from music, from painting, and just plain everyday observation.

In fact, the most interesting writing I did during those days was the plain everyday observations that I recorded in my journal. Descriptions of a neighbor. Long verbatim accounts of overheard conversations. Local gossip. A kind of reporting, a style of “seeing” and “hearing” that would later seriously influence me, though I was unaware of it then, for all my “formal” writing, the stuff that I polished and carefully typed, was more or less fictional.

By the time I was seventeen, I was an accomplished writer. Had I been a pianist, it would have been the moment for my first public concert. As it was, I decided I was ready to publish. I sent off stories to the principal literary quarterlies, as well as to the national magazines, which in those days published the best so-called “quality” fiction—Story, The New Yorker, Harper’s Bazaar, Mademoiselle, Harper’s, Atlantic Monthly—and stories by me duly appeared in those publications.

Then, in 1948, I published a novel: Other Voices, Other Rooms. It was well received critically, and was a best seller. It was also, due to an exotic photograph of the author on the dust jacket, the start of a certain notoriety that has kept close step with me these many years. Indeed, many people attributed the commercial success of the novel to the photograph. Others dismissed the book as though it were a freakish accident: “Amazing that anyone so young can write that well.” Amazing? I’d only been writing day in and day out for fourteen years! Still, the novel was a satisfying conclusion to the first cycle in my development.

A short novel, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, ended the second cycle in 1958. During the intervening ten years I experimented with almost every aspect of writing, attempting to conquer a variety of techniques, to achieve a technical virtuosity as strong and flexible as a fisherman’s net. Of course, I failed in several of the areas I invaded, but it is true that one learns more from a failure than one does from a success. I know I did, and later I was able to apply what I had learned to great advantage. Anyway, during that decade of exploration I wrote short-story collections (A Tree of Night, A Christmas Memory), essays and portraits (Local Color, Observations, the work contained in The Dogs Bark), plays (The Grass Harp, House of Flowers), film scripts (Beat the Devil, The Innocents), and a great deal of factual reportage, most of it for The New Yorker.

In fact, from the point of view of my creative destiny, the most interesting writing I did during the whole of this second phase first appeared in The New Yorker as a series of articles and subsequently as a book entitled The Muses Are Heard. It concerned the first cultural exchange between the U.S.S.R. and the U.S.A.: a tour, undertaken in 1955, of Russia by a company of black Americans in Porgy and Bess. I conceived of the whole adventure as a short comic “nonfiction novel,” the first.

Some years earlier, Lillian Ross had published Picture, her account of the making of a movie, The Red Badge of Courage; with its fast cuts, its flash forward and back, it was itself like a movie, and as I read it I wondered what would happen if the author let go of her hard linear straight-reporting discipline and handled her material as if it were fictional—would the book gain or lose? I decided, if the right subject came along, I’d like to give it a try: Porgy and Bess and Russia in the depths of winter seemed the right subject.

The Muses Are Heard received excellent reviews; even sources usually unfriendly to me were moved to praise it. Still, it did not attract any special notice, and the sales were moderate. Nevertheless, that book was an important event for me: while writing it, I realized I just might have found a solution to what had always been my greatest creative quandary.

For several years I had been increasingly drawn toward journalism as an art form in itself. I had two reasons. First, it didn’t seem to me that anything truly innovative had occurred in prose writing, or in writing generally, since the 1920s; second, journalism as art was almost virgin terrain, for the simple reason that very few literary artists ever wrote narrative journalism, and when they did, it took the form of travel essays or autobiography. The Muses Are Heard had set me to thinking on different lines altogether: I wanted to produce a journalistic novel, something on a large scale that would have the credibility of fact, the immediacy of film, the depth and freedom of prose, and the precision of poetry.

It was not until 1959 that some mysterious instinct directed me toward the subject—an obscure murder case in an isolated part of Kansas—and it was not until 1966 that I was able to publish the result, In Cold Blood.

In a story by Henry James, I think The Middle Years, his character, a writer in the shadows of maturity, laments: “We live in the dark, we do what we can, the rest is the madness of art.” Or words to that effect. Anyway, Mr. James is laying it on the line there; he’s telling us the truth. And the darkest part of the dark, the maddest part of the madness, is the relentless gambling involved. Writers, at least those who take genuine risks, who are willing to bite the bullet and walk the plank, have a lot in common with another breed of lonely men—the guys who make a living shooting pool and dealing cards. Many people thought I was crazy to spend six years wandering around the plains of Kansas; others rejected my whole concept of the “nonfiction novel” and pronounced it unworthy of a “serious” writer; Norman Mailer described it as a “failure of imagination”—meaning, I assume, that a novelist should be writing about something imaginary rather than about something real.

Yes, it was like playing high-stakes poker; for six nerve-shattering years I didn’t know whether I had a book or not. Those were long summers and freezing winters, but I just kept on dealing the cards, playing my hand as best I could. Then it turned out I did have a book. Several critics complained that “nonfiction novel” was a catch phrase, a hoax, and that there was nothing really original or new about what I had done. But there were those who felt differently, other writers who realized the value of my experiment and moved swiftly to put it to their own use—none more swiftly than Norman Mailer, who has made a lot of money and won a lot of prizes writing nonfiction novels (The Armies of the Night, Of a Fire on the Moon, The Executioner’s Song), although he has always been careful never to describe them as “nonfiction novels.” No matter; he is a good writer and a fine fellow and I’m grateful to have been of some small service to him.

The zigzag line charting my reputation as a writer had reached a healthy height, and I let it rest there before moving into my fourth, and what I expect will be my final, cycle. For four years, roughly from 1968 through 1972, I spent most of my time reading and selecting, rewriting and indexing my own letters, other people’s letters, my diaries and journals (which contain detailed accounts of