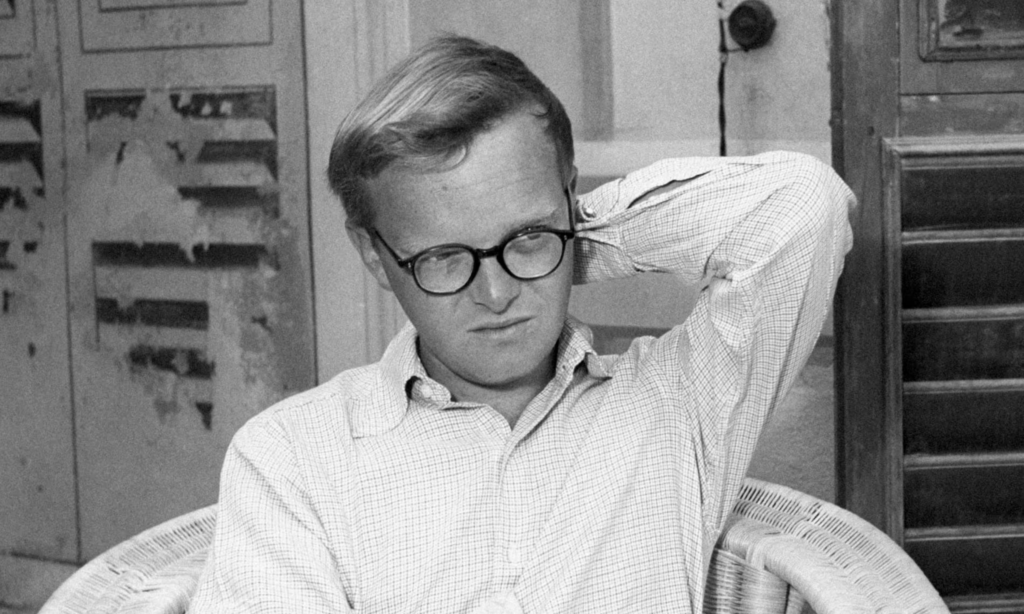

Preface To The Dogs Bark, Truman Capote

PREFACE TO THE DOGS BARK

It must have been the spring of 1950 or 1951, since I have lost my notebooks detailing those two years. It was a warm day late in February, which is high spring in Sicily, and I was talking to a very old man with a mongolian face who was wearing a black velvet Borsalino and, disregarding the balmy, almond-blossom-scented weather, a thick black cape.

The old man was André Gide, and we were seated together on a sea wall overlooking shifting fire-blue depths of ancient water.

The postman passed by. A friend of mine, he handed me several letters, one of them containing a literary article rather unfriendly toward me (had it been friendly, of course no one would have sent it).

After listening to me grouse a bit about the piece, and the unwholesome nature of the critical mind in general, the great French master hunched, lowered his shoulders like a wise old … shall we say buzzard?, and said, “Ah, well. Keep in mind an Arab proverb: ‘The dogs bark, but the caravan moves on.’ ”

I’ve often remembered that remark—occasionally in a gaga romantic way, thinking of myself as a planet wanderer, a Sahara tourist approaching through darkness desert tents and desert campfires where dangerous natives lurk listening to the warning barkings of their dogs. It seems to me that I’ve spent a great bit of time taming or eluding natives and dogs, and the contents of this book rather prove this. I think of them, these descriptive paragraphs, these silhouettes and souvenirs of places and persons, as a prose map, a written geography of my life over the last three decades, more or less from 1942 to 1972.

Everything herein is factual, which doesn’t mean that it is the truth, but it is as nearly so as I can make it. Journalism, however, can never be altogether pure—nor can the camera, for after all, art is not distilled water: personal perceptions, prejudices, one’s sense of selectivity pollute the purity of germless truth.

The earliest pieces in the present volume, youthful impressions of New Orleans and Tangier, Ischia, Hollywood, Spanish trains, Moroccan festivals, et al., were collected in Local Color, a slim limited edition published in 1951 and now long out-of-print. I use the present occasion to reissue its contents for two reasons: the first being nostalgia, a reminder of a time when my eye was less narrowed and more lyric; the second, because these small impressions are the opening buds, the initial thrust of an interest in nonfiction writing, a genre I invaded in a more ambitious manner five years later with The Muses Are Heard, which also has appeared separately as a small book.

The Muses Are Heard is the one work of mine I can truly claim to have enjoyed writing, an activity I’ve seldom associated with pleasure. I imagined it as a brief comic novel; I wanted it to be very Russian, not in the sense of being reminiscent of Russian writing, but rather of some Czarist objet, a Fabergé contrivance, one of his music boxes, say, that trembled with some glittering, precise, mischievous melody.

Many in the cast of characters, Americans as well as Soviets, considered The Muses Are Heard just plain mischievous. However, in my journalistic experience it would seem that I’ve never described anyone to his or her satisfaction; or if, initially, some person was not unhappy with my revelations or small portraits, friends and relatives soon talked the subject into nit-picking misgivings.

Of all my sitters, the one most distressed was the subject of The Duke in His Domain, Marlon Brando. Though not claiming any inaccuracy, he apparently felt it was an unsympathetic, even treacherous intrusion upon the secret terrain of a suffering and intellectually awesome sensibility. My opinion? Just that it is a pretty good account, and a sympathetic one, of a wounded young man who is a genius, but not markedly intelligent.

However, the Brando profile interests me for literary reasons; indeed, that was why I wrote it—to accept a challenge and underline a literary point. It was my contention that reportage could be as groomed and elevated an art as any other prose form—the essay, short story, novel—a theory not so entrenched in 1956, the year the piece was printed, as it is today, when its acceptance has become perhaps a bit exaggerated. My thinking went: What is the lowest level of journalistic art, the one most difficult to turn from a sow’s ear into a silk purse? The movie star “interview,” Silver Screen stuff: surely nothing could be less easily elevated than that!

After selecting Brando as the specimen for the experiment, I checked my equipment (the main ingredient of which is a talent for mentally recording lengthy conversations, an ability I had worked to achieve while researching The Muses Are Heard, for I devoutly believe that the taking of notes—much less the use of a tape recorder!—creates artifice and distorts or even destroys any naturalness that might exist between the observer and the observed, the nervous hummingbird and its would-be captor).

It was a lot to remember, that long stretch of hours of Brando muttering and meandering, but I wrote it all out the morning after the “interview,” then spent a month shaping it toward the ultimate result. What I learned most from it was how to control “static” writing, to reveal character and sustain mood unaided by a narrative line—the latter being, to a writer, what a rope and pickaxe are to a mountain climber.

In The Dogs Bark two pieces especially demonstrate the difference between narrative and “static” writing. A Ride Through Spain was a lark; buoyed along by its anecdotal nature, it skimmed off the end of a Black Wing pencil in a matter of hours. But something like A House on the Heights, where all the movement depends on the writing itself, is a matter of how the sentences sound, suspend, balance and tumble; a piece like that can be red hell, which is why I have more affection for it than A Ride Through Spain, even though I know the latter is better, or at least more effective.

Much of the substance of this book appeared over the years in various publications, but they have never before found shelter under one roof. One of them, Lola, has a curious history. Written to exorcise the ghost of a lost friend, it was bought by an American magazine, where for years it reposed unprinted because the magazine’s editor decided he loathed it; he said he didn’t know what it was about, and moreover, found it forbidding, black.

I disagree; still, I can see what he meant, for instinctively he must have seen through the sentimental disguises of this true tale and realized, without altogether recognizing, what it in fact concerned: the perils, the dooms of not perceiving and accepting the limits of one’s supposed identity, the classifications imposed by others—a bird that believes it is a dog, Van Gogh insisting that he was an artist, Emily Dickinson a poet. But without such misjudgments and such faiths, the seas would sleep, the eternal snows remain untracked.

1973

The End