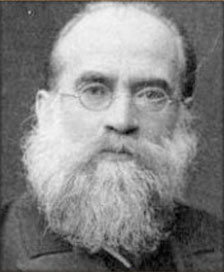

Lev (Leo) Mikhailovich Lopatin (Russian: Лев Миха́йлович Лопа́тин; 13 June 1855, Moscow – 21 March 1920, Moscow)

Russian idealist philosopher and psychologist, professor at Moscow University, long-term chairman of the Moscow Psychological Society and editor of the journal “Problems of Philosophy and Psychology”. Closest friend and opponent of V. S. Solovyov since early childhood. Lopatin was the creator of the first system of theoretical philosophy in Russia; he called his teaching, set out in his work “Positive Tasks of Philosophy” and many articles, “concrete spiritualism”. The thinker’s main works are devoted to issues of the theory of knowledge, metaphysics, psychology, ethics and the history of philosophy. In the theory of knowledge, Lopatin acted as a supporter of rationalism, a consistent critic of empiricism and a defender of speculation. In psychology, he developed the method of introspection, substantiated the substantial unity of consciousness and the identity of the individual, defended the creative nature of consciousness and free will. In metaphysics, the philosopher developed an original theory of creative causality, with the help of which he proved someone else’s animation, the existence of God and the external world; the key idea of Lopatin’s spiritualism was the inner spirituality of all things, directly revealed in the activity of our inner self. In his ethical works, the philosopher criticized the morality of utilitarianism, defended the ideas of the immortality of the soul and the moral world order. Lopatin’s historical and philosophical works are devoted to ancient, modern and contemporary philosophy; of considerable importance are also works devoted to a critical analysis of the works of his contemporaries. According to researchers, Lopatin’s works, along with the works of other thinkers, laid the foundation for an independent Russian philosophical tradition.

Early Years

Lev Mikhailovich Lopatin was born on June 1, 1855 in Moscow, into the family of the famous judicial figure Mikhail Nikolaevich Lopatin and his wife Ekaterina Lvovna, née Chebysheva. The philosopher’s father, Mikhail Nikolaevich, came from an old noble family of the Tula province, known since the beginning of the 16th century. The elder Lopatin graduated from the law faculty of Moscow University and served in the judicial department in various institutions in Moscow; at the end of his life, he headed one of the departments of the Moscow Court of Justice. He was a moderate liberal, a supporter of the reforms of Alexander II and the author of publicistic articles. His colleagues knew him as an honest, fair and incorruptible judge. The philosopher’s mother, Ekaterina Lvovna, was the sister of the famous mathematician P. L. Chebyshev. M. N. and E. L. Lopatin had five children: Nikolai, Lev, Alexander, Vladimir and Ekaterina (the last son, Mikhail, died in childhood). All the Lopatin children became famous creative people. The eldest son, Nikolai Mikhailovich, became a famous folklorist, collector and publisher of Russian folk songs. The younger brothers, Alexander and Vladimir Mikhailovich, became judicial figures, and Vladimir was also an outstanding actor who played at the Moscow Art Theater. Their sister Ekaterina Mikhailovna became famous as a writer, writing under the pseudonym K. Yeltsova. Lev Mikhailovich was the second son in the family and was named after his maternal grandfather L. P. Chebyshev. According to the birth register, Lev was baptized on June 11, 1855, and his godfather was his uncle, the mathematician P. L. Chebyshev. The future philosopher spent his childhood in Moscow, in the house of the merchant Yakovlev in Nashchokinsky Lane, where his parents rented an apartment. Lev grew up a weak, thin, sickly teenager; his distinctive feature was a combination of physical helplessness with a clear and subtle mind. In 1868, he entered the 3rd grade of the newly founded private gymnasium of L. I. Polivanov, which he successfully graduated from in 1875. An outstanding teacher, L. I. Polivanov was able to instill in his students an interest in literature and art. The students of the Polivanov gymnasium created the dramatic “Shakespeare Circle”, in the productions of which the young Lopatin took an active part. According to his contemporaries, Lev had an extraordinary stage talent: he played the roles of Polonius, Lorenzo, Malvolio, Menenius Agrippa, Henry IV, the Miserly Knight and was especially good in the role of Iago. The philosopher retained his love for the theater throughout his life and already in his declining years he was a member of the editorial committee of the Moscow Maly Theater. Of the other teachers at the gymnasium, the greatest influence on Lopatin was the physics and mathematics teacher N. I. Shishkin. An original thinker himself, Shishkin was able to clearly and simply explain the most complex scientific problems; from him Lopatin learned a love for the exact sciences.

In 1872, the Lopatin family settled in their own two-story house on the corner of Khrushchev and Gagarin Lanes. This house became famous in Moscow thanks to the private gatherings that took place there, the so-called Lopatin “Wednesdays”. The head of the family, M. N. Lopatin, maintained friendly relations with many outstanding people of his time. Every Wednesday evening, representatives of the scientific and creative intelligentsia gathered in his house for dinner: professors, writers, actors, judicial and public figures. They came here to exchange news, opinions, listen to new literary and musical works, and argue on scientific and socio-political topics. Here one could meet such people as S. M. Solovyov, I. E. Zabelin, I. S. Aksakov, D. F. Samarin, A. F. Pisemsky, A. I. Koshelev, N. P. Gilyarov-Platonov, S. A. Yuryev, L. I. Polivanov, V. I. Gerye, V. O. Klyuchevsky, A. A. Fet, F. I. Tyutchev, L. N. Tolstoy and many others. These gatherings had a great influence on M. N. Lopatin’s children, especially on Lev. In this old Moscow, Slavophile environment, his views and ideals in life were formed. Young Lopatin especially benefited from communication with S. A. Yuryev, in conversations with whom he learned his first philosophical lessons.

Lopatin’s friendship with Vladimir Solovyov had a huge influence on his fate. The families of their fathers, M. N. Lopatin and S. M. Solovyov, lived in the neighborhood and maintained close relations, and in the summer they vacationed together at the Pokrovskoe-Streshnevo estate near Moscow. Lev met Vladimir when the former was 7 and the latter 9 years old. Later, the philosophers recalled how, as teenagers, they organized entertainment in Pokrovskoe-Streshnevo Park, pretending to be ghosts and scaring local residents. Lopatin and Solovyov began to take an interest in philosophical questions early on, and their intellectual development proceeded in parallel. Lopatin recalled that when he was 12, Solovyov, who was a materialist at the time, “shaken to the core” his childhood beliefs. From that time on, he began to painfully develop his own worldview in a constant struggle with Solovyov. The views of the young Solovyov underwent a rapid evolution: after becoming fascinated with materialism, he became a follower of Schopenhauer, and then returned to the Christian church faith. According to Lopatin’s memoirs, by the age of 15 he had come to terms with Solovyov on philosophical idealism, and at 17 he became his complete like-minded person. However, their philosophical paths later diverged: despite Solovyov’s influence, Lopatin did not become his follower and developed his own teaching, which he defended until the end of his life. The friendship between the two philosophers remained unchanged, however; many of Solovyov’s poems are dedicated to Lopatin.

At Moscow University

After graduating from high school in 1875, Lopatin entered the history and philology department of Moscow University. That year, after the death of P. D. Yurkevich, the philosophy department at the university was occupied by two people: the young V. S. Solovyov, who had just defended his master’s dissertation, and Professor M. M. Troitsky, who had arrived from Warsaw. Solovyov, however, soon left the university, and Professor Troitsky remained the only representative of philosophy at the department. Troitsky was a positivist, a follower of English empiricism in the spirit of J. S. Mill and H. Spencer, and had a negative attitude towards any metaphysics. Lopatin, whose views had already taken shape by that time, did not meet with any sympathy from him. In 1879, he graduated from the university with a candidate’s degree and expressed a desire to continue his scientific work; however, Troitsky opposed his remaining at the department, and Lev Mikhailovich was forced to look for another job. At one time he taught Russian at a real school, and then got a job as a teacher of literature and history at his native gymnasium of L. I. Polivanov and at the girls’ gymnasium of S. A. Arsenyeva. The philosopher maintained ties with these educational institutions until the end of his life. In 1880, Lopatin, as Polivanov’s assistant, took part in organizing the celebrations on the occasion of the opening of the monument to A. S. Pushkin; here he met the writer F. M. Dostoevsky, who in a letter to his wife described him as “an extremely intelligent person, very thoughtful, extremely decent and to the highest degree of my convictions.”

In 1881, at the invitation of V. I. Gerye, Lopatin began teaching at the Faculty of History and Philosophy of the Higher Courses for Women. His literary activity began during these years: in 1881, his first article, “Experiential Knowledge and Philosophy,” was published in “Russkaya Mysl,” and in 1883, the article “Faith and Knowledge.” Both articles were subsequently included in Volume 1 of his main work, “Positive Tasks of Philosophy.” Soon, at the insistence and patronage of V. I. Gerye, Lopatin managed to return to Moscow University. In 1884, he successfully passed his master’s exam, and the following year, after giving trial lectures on Kant’s theory of causality, he began teaching as a private lecturer. In the spring of 1886, he defended his master’s thesis, the text of which, under the title “The Field of Speculative Questions”, was published in the same year as Volume 1 of “Positive Tasks of Philosophy”. At the defense of the dissertation, Professor Troitsky spoke out against Lopatin, but the dean of the faculty, who favored the candidate, read his caustic review so skillfully that no one noticed his causticity. In the same year, Troitsky resigned, and the philosophy department was occupied by Professor N. Ya. Grot, who arrived from Novorossiysk. Lopatin established friendly relations with Grot, and his further professional growth did not encounter any obstacles. In 1891, he successfully defended his doctoral dissertation on the topic of “The Law of Causal Relationship as the Basis of Speculative Knowledge of Reality”, and in the same year published it as Volume 2 of “Positive Tasks of Philosophy”. From 1892 Lopatin was an extraordinary professor, and from 1897 an ordinary professor at Moscow University. Lopatin’s entire subsequent life was connected with Moscow University, within whose walls he worked for a total of 35 years – longer than any other pre-revolutionary philosophy teacher. At the same time, he continued to lecture at two gymnasiums and at the Higher Women’s Courses.

During his years of teaching, Lopatin gave many lecture courses, some of which were published as separate editions. These include, first of all, courses on the history of ancient and modern philosophy, which were published as lithographed editions in different years. Numerous editions of these courses testify to the constant creative revision to which their author subjected them. The philosopher also gave courses on ancient culture, on Plato and Aristotle, special courses on “European Philosophy in the Current Century”, “Kant’s Philosophy”, “Ethics”, a course on “Basic Problems of Cognition”; In 1894, he began to teach a new course, “Introduction to Philosophy,” and from 1899, a course in psychology. According to the recollections of his listeners, Lopatin’s lectures immersed them in the living element of philosophical creativity and taught students to think independently. His course, “Introduction to Psychology,” made a special impression. Thus, the philosopher and theologian N. S.

Arsenyev recalled:

“Convincingly, clearly, with strong argumentation and — inspiredly — he spoke about the rights of the spirit, about reality, the original decisive reality of the spirit. In mental communication with Lopatin at these lectures, the young man entered into communication with passionate and conscientious and deeply convincing for thought and captivating in the power of moral uplift testimony about the true existence of the spiritual world.” — N. S. Arsenyev. Gifts and Meetings of the Path of Life.

However, not all students found the philosopher’s courses popular: many found them boring, and some believed that Lopatin’s printed publications made a greater impression than his lectures. Over the long years of teaching, thousands of students attended his courses, many of whom later became major thinkers; among them were, for example, philosophers P. A. Florensky, V. F. Ern, V. P. Sventsitsky, G. G. Shpet, A. F. Losev, psychologist P. P. Blonsky, poets V. Ya. Bryusov and A. Bely, and many others. Despite this, Lopatin failed to create his own philosophical school, and only at the end of his life did he have several students, in particular, the son of his friend, professor A. I. Ognev, and later known as a literary scholar P. S. Popov.

In the Moscow Psychological Society

In 1885, the Psychological Society was created at Moscow University, uniting many philosophers, psychologists and representatives of other sciences. The society was conceived not only as a psychological, but also as a philosophical one; the initiator of its creation and the first chairman was Professor M. M. Troitsky. According to the charter, the Society had the goal of developing and disseminating psychological knowledge; it had its own printed organ, the Transactions of the Moscow Psychological Society, which was published every few years, and carried out scientific translations. From the very moment of the creation of the Society, Lopatin took an active part in its activities; he invariably attended its meetings, delivered reports, and participated in debates.

In 1887, after Troitsky’s resignation, Professor N. Ya. Grot became the new chairman of the Society. With Grot’s arrival, the Society’s activities took on a broader character: in 1889, on his initiative, the Society began publishing the journal “Problems of Philosophy and Psychology”, which came out 4-6 times a year. In a short time, “Problems of Philosophy and Psychology” became the largest Russian philosophical journal and a unifying center of Russian philosophical thought. Grot had the ability to bring people of different beliefs together; under his leadership, the Psychological Society turned into a close circle of people united by common goals. According to Lopatin, during Grot’s chairmanship, the Psychological Society became one of the most popular centers of Russian education.

Since the late 1880s, Lopatin’s life was closely connected with the activities of the Psychological Society. His articles were published in the “Proceedings of the Moscow Psychological Society”, and with the appearance of the journal “Problems of Philosophy and Psychology”, he became one of its main authors. Already in 1890, the journal published a series of his articles on moral philosophy, in which he formulated his ethical views. Then, throughout the 1890s and early 1900s, the philosopher published articles on psychology in the journal, which formed the basis of his psychology course, read at the Higher Women’s Courses and published as a lithographed edition in 1903. Finally, from the early 1900s, Lopatin began publishing articles of general philosophical content in the journal, developing the ideas of his main work, Positive Tasks of Philosophy. To this should be added obituary articles and articles devoted to the characteristics of thinkers of the past, published in different years.

The articles in this series were published in 1911 as a separate book, Philosophical Characteristics and Speeches. In total, over the years of his collaboration with the journal Questions of Philosophy and Psychology, Lopatin published more than 50 articles in it. From 1894 he took part in editing the journal, and in 1896, during Grot’s illness, he became one of its co-editors. In 1899, after the death of N. Ya. Grot, Lopatin was elected the new chairman of the Psychological Society and from that moment headed the Society until his own death in 1920. At the same time, he continued to edit the journal “Problems of Philosophy and Psychology”, first together with V. P.

Preobrazhensky, and after the latter’s death, together with Prince S. N. Trubetskoy. Prince S. N. Trubetskoy was one of Lopatin’s closest friends; in 1902, he organized the student Historical and Philosophical Society at Moscow University, to which Lopatin was invited to work, heading its philosophical section. However, in September 1905, Trubetskoy, elected rector of Moscow University, died of a stroke. After his death, the management of the journal “Problems of Philosophy and Psychology” passed entirely into the hands of Lopatin, who remained its sole editor until the publication was closed in 1918. At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, the Psychological Society suffered a number of significant losses: one after another, its active members M. M. Troitsky, N. Ya. Grot, V. P. Preobrazhensky, S. S. Korsakov, V. S. Solovyov, A. A. Tokarsky, N. V. Bugayev, S. N. Trubetskoy died, which could not but affect the quality of its work. The revolutionary events of 1905-1906 also had a negative impact on the work of the Society. Despite this, by the beginning of the 1910s, the Society managed to emerge from the crisis; the journal “Problems of Philosophy and Psychology” continued to be published in large print runs and introduce readers to the latest philosophical ideas. By this time, Lopatin, who had concentrated in his hands the post of chairman of the Society and editor of the journal, became the main representative of philosophy in Moscow. In 1911, the Psychological Society solemnly celebrated the 30th anniversary of Lopatin’s scientific work. Representatives of almost all of Moscow’s scientists, educational and literary societies attended the ceremonial meeting held on December 11. Welcome addresses were read from the Moscow Psychological Society, Moscow University, Moscow Higher Women’s Courses, the Society of Lovers of Russian Literature, Moscow Societies: Naturalists, Neurologists and Psychiatrists, Mathematical, Legal, Religious and Philosophical, Moscow Literary and Artistic Circle, S. A. Arsenyeva’s Women’s Gymnasium and L. I. Polivanov’s Men’s Gymnasium, as well as from fellow faculty members, male and female students. Speeches were given by Professors G. I. Chelpanov, P. I. Novgorodtsev, V. M. Khvostov and others. In his speeches, Lopatin was called “one of the most significant representatives of philosophical thought in Russia”, “an outstanding national thinker” and “a knight of philosophy”. It was stated that he was one of the creators of Russian idealistic philosophy, laid a solid foundation for philosophical psychology and contributed to the development of the Russian philosophical language. Lopatin’s works were spoken of as “a living and brilliant revelation of independent Russian thought”, and his anniversary was described as “a holiday of Russian philosophy”. The philosopher was touched by the high assessment of his works and in his response he admitted that he had never counted on the triumph of his ideas during his lifetime and worked mainly for future generations. For the anniversary, a “Philosophical Collection” dedicated to Lopatin was published; the first volume of his “Positive Tasks of Philosophy” was reissued and a collection of articles, “Philosophical Characteristics and Speeches”, was published.

The Last Years of Life and Death

Lopatin’s life was typical of a philosopher: not rich in external events, it was filled mainly with internal mental work. The philosopher never married and spent his entire life as a bachelor. He always lived in the same house – his parents’ mansion on Gagarinsky Lane, from which he never moved and in which he died. In the house itself, he occupied a room on the top floor – the so-called “nursery”, the ceiling of which was so low that V. S. Solovyov, entering, had to bend over so as not to hit his head on the lintel. They said that when the Lopatins settled in this house, Lev Mikhailovich, having looked over the room, said: “Well, I’ll somehow hold out until spring”, – and so he stayed in it for the rest of his life. The philosopher’s father and mother died, his sister sold the house, but Lev Mikhailovich still managed to get his room from the new owners, not knowing where and how he could move from it. The philosopher’s way of life also remained unchanged for many years: he worked at night, slept during the day, and got up in the afternoon, which is why he was constantly late for various meetings. He was also late for the lectures he gave and the lessons he taught, and this habit was the subject of good-natured jokes among his colleagues. In the evenings, Lev Mikhailovich went to private meetings, the so-called jour fixes, or simply to visit, where he would sit chatting and drinking tea until late at night. Here he often told his scary stories, which he was a great master of. In the summer, he usually went abroad or to the Caucasus, most often to Yessentuki, or stayed at the dacha of one of his friends.

In his work in the Psychological Society and the journal “Problems of Philosophy and Psychology”, Lev Mikhailovich also loved the usual immutability. He chaired the meetings, spoke in the debates, reviewed the manuscripts received by the journal, and gave his apt reviews. All technical editorial work was carried out by his assistant, the widow of the historian M. S. Korelin, the secretary of the journal N. P. Korelin. As a leader, Lopatin was very conservative: he did not like innovations and tried to avoid everything that required a lot of energy from him. When the famous French philosopher A. Bergson decided to come to Moscow, Lopatin opposed his arrival, since he did not want to take on the troubles associated with his reception. For this, his colleagues and acquaintances were very annoyed with him. Lopatin had a negative attitude towards the latest trends in philosophy and did not want to study the works of new European authors, being convinced that the old ones were still better. “Ancient means good work,” Lev Mikhailovich liked to say. He especially disliked the neo-Kantian schools that spread at the beginning of the 20th century – G. Cohen, G. Rickert and P. G. Natorp, whose teachings seemed obscure and incomprehensible to him. When a group of young neo-Kantians decided to publish the philosophical journal Logos in Russia, Lopatin refused them any support, and the journal began to be published without his participation. At the same time, Lopatin was very sensitive to those new trends in philosophy that were consonant with his own ideas. In particular, he was one of the first to highly appreciate the pragmatism of W. James, who defended the ideas of God’s existence and free will that were dear to him.

On January 12, 1917, on Tatyana’s Day, Lopatin delivered a speech at a ceremonial meeting of Moscow University entitled “Urgent Tasks of Modern Thought.” In his speech, he pointed out the crisis of European culture, gave a brief outline of his philosophical system, and focused on the issues of the origin of evil and the immortality of the soul. In essence, Lopatin summed up his philosophical work and pointed out new paths for the development of philosophy. Lopatin’s speech, published as a separate brochure, made a great impression and evoked many responses. According to S. A. Askoldov, it became the philosopher’s “swan song”. In 1917, the philosopher’s usual way of life was destroyed first by the February Revolution and then by the October Revolution. The socio-political upheavals experienced by the country also affected the scientific world. In 1918, the journal “Problems of Philosophy and Psychology” ceased publication. The Psychological Society was going through a crisis and worked intermittently. Many members of the Society, persecuted by the Bolsheviks, ended up in the White movement or in exile; hunger and devastation reigned in Moscow. In poor health, Lev Mikhailovich had difficulty coping with the difficult living conditions. At that moment, the philosopher felt a calling to fight for raising the religious level of Russian society.

In 1918, he came out with “Theses on the Creation of the World Union for the Revival of Christianity”, preserved in the papers of Father Pavel Florensky. These theses spoke of the need to unite Christians of all faiths “to combat religious unbelief and crude worship of material culture and their practical consequences in political, social, economic life and in the entire structure and way of life of individuals.” In the last months of his life, the philosopher was cheerful and looked to the future with optimism; he told his acquaintances that a person will not die until he has completed his mission on earth. In November 1919, Lopatin wrote to N. P. Korelina: “I am convinced that everything that is happening is necessary, that it represents a painful and agonizing process of the rebirth of humanity (yes, humanity, and not just Russia) from all the untruth that has crushed it, and that it will lead to something good, bright, and completely new.” However, the philosopher’s physical strength was weakening; in March 1920, he fell ill with influenza, complicated by pneumonia, and on March 21, he died quietly in his room in the presence of a few students and acquaintances. According to the memoirs of A. I. Ognev, the philosopher’s last words were: “We’ll understand everything there.”

The philosopher was buried on the territory of the Novodevichy Convent next to the grave of his brother and not far from the grave of V. S. Solovyov. Several obituaries were dedicated to him, and a book by A. I. Ognev, “Lev Mikhailovich Lopatin”, published in 1922.

The personality of the philosopher

According to his contemporaries, Lopatin’s characteristic feature was a combination of physical weakness and spiritual strength. Short in stature, thin, puny, with thin limbs and weak muscles, he was not adapted to any physical activity. There was something helpless and childish in his figure, gestures, and gait; he walked hunched over and never straightened up to his full height. The philosopher’s health was also poor: he was often ill and was very afraid of colds, which is why he dressed warmly in any weather; In winter he wrapped himself up so much that only his eyes were visible from under his lambskin hat, and his entire face was wrapped in a long knitted scarf. They also said that in summer he wore warm winter galoshes, which is why he was known as a great eccentric and original. He did not understand practical matters and was constantly in need of someone’s help. His old servant Sergei, hired by his parents and acting as a kind of nanny for the philosopher, remained with him until the end of his life. According to the stories, Lopatin had a pleasant face with a high convex forehead, light hair thrown back and large, expressive, intelligent eyes. These eyes lit up with a special sparkle when the philosopher argued about something or told his scary stories; according to E. N. Trubetskoy, they possessed the power of some kind and gentle hypnosis. In the weak, feeble body of the philosopher, however, lived a big and kind soul. Lev Mikhailovich sincerely loved people, knew how to enter into their needs, share their sorrows and joys. Being a believing Christian, he strove to embody the gospel ideal in his life, actively helping people in trouble and need. According to his younger brother, there was never a case when Lev Mikhailovich refused anyone spiritual or material help. People often turned to him for advice and support, and he always found the right words for the sufferer. Demanding of himself, Lopatin was indulgent to others, did not hold a grudge against anyone and easily forgave insults. Pride, conceit, ambition and envy were organically alien to him. Meek and gentle by nature, he was incapable of causing harm or offending another person. According to the memoirs of M. K. Morozova, while teaching at the gymnasium, Lopatin gave all his students A’s, and if someone did not answer the lesson, he would get angry and threaten to give them a B or ask next time. Lev Mikhailovich easily got along with people and found a common language with them, regardless of their age and social status. He was especially good at getting along with children, to whom he willingly gave gifts and who loved him very much.

The philosopher lived very modestly. The only furniture in his small room was a bed, two tables and a few chairs. The Lopatins did not have electricity, and the philosopher worked with a kerosene lamp until the end of his life. Here, on a table covered with books, on a scrap of paper, with a pencil, he wrote his compositions in small handwriting. According to his brother, Lopatin was a convinced ascetic: he viewed his body as a burden and a liability, he feared the dependence of the spirit on the body and fought against physical shackles in every possible way. From his living environment, he demanded that little that freed him from physical oppression and gave him a sense of independence from material conditions. He viewed everything else as an excess, which he avoided in every possible way and which he found burdensome. He treated women chivalrously, and was intimately friendly with many of them, but he did not want to tie himself to marriage, fearing to lose his usual freedom and independence.

As a scientist, Lopatin was distinguished by his extreme independence of thought. In philosophy, he was no one’s disciple. He did not join any philosophical school, did not look to authorities, and consistently developed his own original worldview. Lopatin was one of the few Russian thinkers who remained outside of Kant’s influence. He considered Kantianism a dead-end branch of philosophy and preferred to rely on the thinkers of the pre-Kantian era, which is why he was reproached for “philosophical backwardness.” Being an insightful critic, he assessed every teaching by its internal strength and consistency and rejected everything that did not meet these criteria. Gentle and compliant by nature, he became dogmatic and intolerant when it came to philosophical issues, and often argued fiercely, proving his case. Lopatin’s own thinking was distinguished by exceptional clarity. He was characterized by a desire for precise formulations and simplicity of presentation. He was able to explain the most difficult philosophical concepts in an accessible language to anyone who was not well versed in philosophy. When preparing his articles, he would read them to the editorial secretary N. P. Korelina, and if she did not understand something, he would rewrite the work several times until he achieved complete clarity. Lopatin’s works are distinguished by their extreme thoughtfulness; according to P. S. Popov, the philosopher would cherish his thoughts for a long time, put them into clear formulations and memorize them, and only then would he sit down and write them down on paper. Even when preparing for a discussion, he would think over and write down his arguments in advance, outlining the possible responses of his opponent and his objections to them. This made him an invulnerable debater.

Of particular interest in characterizing Lopatin are his scary stories. These stories were very popular, especially among young people, and Lev Mikhailovich was often specially invited to dinner to listen to his stories. He told them masterfully, expressively playing with his eyes and intonation of his voice, so that everyone present felt eerie and many were afraid to walk through the dark room afterwards. The peculiarity of these stories was that they all contained a mystical element; their usual plot consisted of the appearance of the soul of the deceased. These stories were closely connected with Lopatin’s fundamental conviction – the conviction of the immortality of the human personality. The strength of their artistic impact was determined by the faith in their reality, which is transmitted from the storyteller to the listener: the personality does not die, it lives beyond the grave, and on occasion “plays pranks” if it has not found peace for itself – this is the main motive of Lopatin’s stories. Lopatin was a convinced mystic, believed in communication between the living and the dead and saw mystical meaning in everything real. He took spiritualism seriously and treasured the results of his penetration into the spiritualistic realm, although he never spoke about it publicly. The realm of reality and the mystical realm were for him two sides of one reality, and this conviction left its mark on his philosophy.

Teaching

In his philosophical views, Lopatin belonged to the school called spiritualism or metaphysical personalism. The essence of this teaching is that it takes the spirit (Latin: spiritus) or personality (Latin: persona) as the main, primary essence. In this it differs both from materialism, which sees the essence of things in matter, and from Platonic idealism, which places the beginning of things in abstract ideas. René Descartes is traditionally considered the founder of this school, although its roots go back to ancient philosophy. The greatest representatives of spiritualism after Descartes were G. V. Leibniz, J. Berkeley and Maine de Biran. The term “spiritualism” was first applied to his teaching by Maine de Biran’s follower, the French philosopher V. Cousin. In Germany, spiritualistic ideas were developed by Leibniz’s followers J. F. Herbart, R. G. Lotze, J. G. Fichte the Younger, and G. Teichmüller. The latter, who called his teaching “personalism,” taught at Yuryev University, where he created a special school of followers; his ideas were supported by Russian philosophers A. A. Kozlov, E. A. Bobrov, S. A. Askoldov, and N. O. Lossky. An original version of Leibnizian monadology was also developed by Lopatin’s senior colleagues in the Psychological Society, N. V. Bugayev and P. E. Astafyev.

Of the thinkers who influenced Lopatin, Descartes and Leibniz are most often named, the great importance of whose ideas was emphasized by the philosopher himself. However, the definition of Lopatin as a “Russian Leibnizian” found in literature is incorrect; Leibniz was only one of many thinkers who influenced the formation of his ideas. Also significant was the influence of Berkeley, whose “Treatise on the Principles of Human Knowledge” was the first philosophical book read by Lopatin, and Maine de Biran, whose ideas formed the basis of Lopatin’s psychology. Some researchers also note the influence of the ideas of J. G. Fichte, A. Schopenhauer and Lotze. Particularly noteworthy is the influence of the early Vladimir Solovyov, who in his youth adhered to spiritualistic ideas. His metaphysics, set out in “Readings on God-Manhood”, represented an original development of Leibniz’s monadology. However, Solovyov subsequently moved away from Leibnizianism and often criticized Lopatin’s spiritualism from the standpoint of his “metaphysics of All-Unity.” In general, researchers note Lopatin’s great independence in developing philosophical ideas and the originality of his teaching, which does not allow him to be classified as a student of any other thinker. Lopatin’s spiritualism became one of the first creations of original Russian philosophy.

The philosopher himself called his teaching concrete spiritualism, contrasting it with Hegel’s abstract teaching about the World Spirit. The spirit in Lopatin’s teaching is not an abstract idea, but a living, active force that exists before any embodiment in the life of nature and humanity. The main provisions of Lopatin’s spiritualism: self-reliance of inner experience; substantial unity of consciousness; identity of personality; creative activity of the human spirit; free will; creative causality as a universal law of reality; the principle of the relativity of phenomena and substances; the inner spirituality of all that exists; the existence of God and the moral world order; the immortality of the soul. In his work “Urgent Tasks of Modern Thought,” the philosopher formulated the essence of his teaching as follows:

“All reality, both in us and outside of us, is spiritual in its inner essence; spiritual, ideal forces are realized in all phenomena around us, they are only hidden from us by the forms of our external sensory perception of them; on the contrary, in our soul, in the immediate experiences and acts of our inner Self, in its properties and definitions, real reality is revealed to us, no longer covered by anything. And what is fundamental in this reality and inseparable from it under any circumstances must also be fundamental in any other reality, if only there is internal unity in the world and if it is not composed of elements that negate each other.” — L. M. Lopatin. Urgent Tasks of Modern Thought.

Main Works

The main work that presented Lopatin’s philosophical teaching was the two-volume monograph “Positive Tasks of Philosophy”. According to the author, the monograph was devoted to substantiating the necessity and possibility of metaphysics; the very title of the work indicated the presence of positive tasks in philosophy, that is, metaphysical knowledge. In the first part of the monograph, the philosopher criticized the empirical theory of knowledge and proved the necessity of metaphysics as a special science; in the second, he expounded his theory of creative causality and gave a brief outline of the system of spiritualistic metaphysics. “Positive Tasks of Philosophy” was a kind of program, in line with which the thinker’s further work developed. Lopatin’s subsequent articles in “Problems of Philosophy and Psychology” were devoted to explaining, developing and deepening the key ideas of “Positive Tasks”. It was here, in these articles, that Lopatin’s philosophical talent was revealed with full force.

All of Lopatin’s articles fall into five cycles, devoted respectively to psychology, metaphysics, ethics, analysis of philosophical teachings of the past and criticism of the latest philosophical trends. The most important is the cycle of articles on issues of psychology, which formed the basis of the course “Introduction to Psychology”. Of these, the following articles should be especially highlighted: “The Phenomenon and Essence in the Life of Consciousness”, “The Concept of the Soul Based on Internal Experience”, “Spiritualism as a Psychological Hypothesis”, “The Question of the Real Unity of Consciousness” and “The Method of Self-Observation in Psychology”. According to Professor V. V. Zenkovsky, “Lopatin can be called – without exaggeration – the most outstanding Russian psychologist; his articles on general and specific issues of psychology retain their high significance to this day.”

Of considerable importance is also a series of articles on the theory of knowledge and metaphysics, the reason for writing which was a polemic with Professor V. I. Vernadsky. The series includes the articles: “Scientific Worldview and Philosophy”, “Axioms of Philosophy”, “Typical Systems of Philosophy” and “Spiritualism as a Monistic System of Philosophy”. The final work of the series was the article “Urgent Tasks of Modern Thought”, containing a brief exposition of the main ideas of the thinker. Of the works of ethical content, it is necessary to note the articles “Critique of the Empirical Principles of Morality”, “Theoretical Foundations of Conscious Moral Life” and two articles on free will, appended to the second volume of “Positive Tasks”. Of considerable interest are also the historical-philosophical and critical articles of the thinker and his three-volume course on the history of philosophy. According to S. L. Frank, written in 1930, “Lopatin’s works should be ranked without reservation among the best and highest achievements of philosophical thought of the last half-century.”

From Brockhaus and Efron

In all his works, Lopatin energetically insists on the necessity of a speculative beginning in any integral worldview. The empirical principle, fully disclosed, not relying on speculation, leads to the inevitable denial of knowledge and skepticism. It is impossible to seek the foundations for developing a worldview in faith alone, since, while rejecting speculation in principle, it constantly proceeds from it in reality. Speculative philosophy is knowledge of real things in their beginnings and final purpose. For the possibility of metaphysical constructions, the question of the law of causality must be of decisive importance. This law, precisely in the fundamental meaning that it has for any direct activity of the mind, that is, as a requirement of productive, or creative, causality, receives real satisfaction only in the spiritualistic worldview.

A review of speculative concepts of reality thus leads Lopatin to a system of concrete spiritualism or to psychological metaphysics. Assuming for the phenomena of the spirit a substance whose properties are essentially different from what is directly given in these phenomena, that is, a transcendental substance, we create a sterile and contradictory concept. If, having rejected any substance, we begin to look at mental life as a pure sequence of absolute states (the point of view of “phenomenism”), we receive a concept of the soul that is deeply at odds with its most basic characteristics and disintegrates into incurable internal contradictions.

There is only one way out: the substance of the soul is not transcendental, but immanent to its phenomena, that is, it reveals or manifests itself and its nature in our mental states. The phenomena of the spirit must be not only indicators, but also a direct realization of its essence.

Based on the concept of the soul as a productive cause, Lopatin tries to defend the principle of free will on psychological grounds (moderate indeterminism). In the question of the essence of the world order, Lopatin adheres to Leibniz’s monadology, which brings him closer to representatives of the Moscow philosophical and mathematical school.