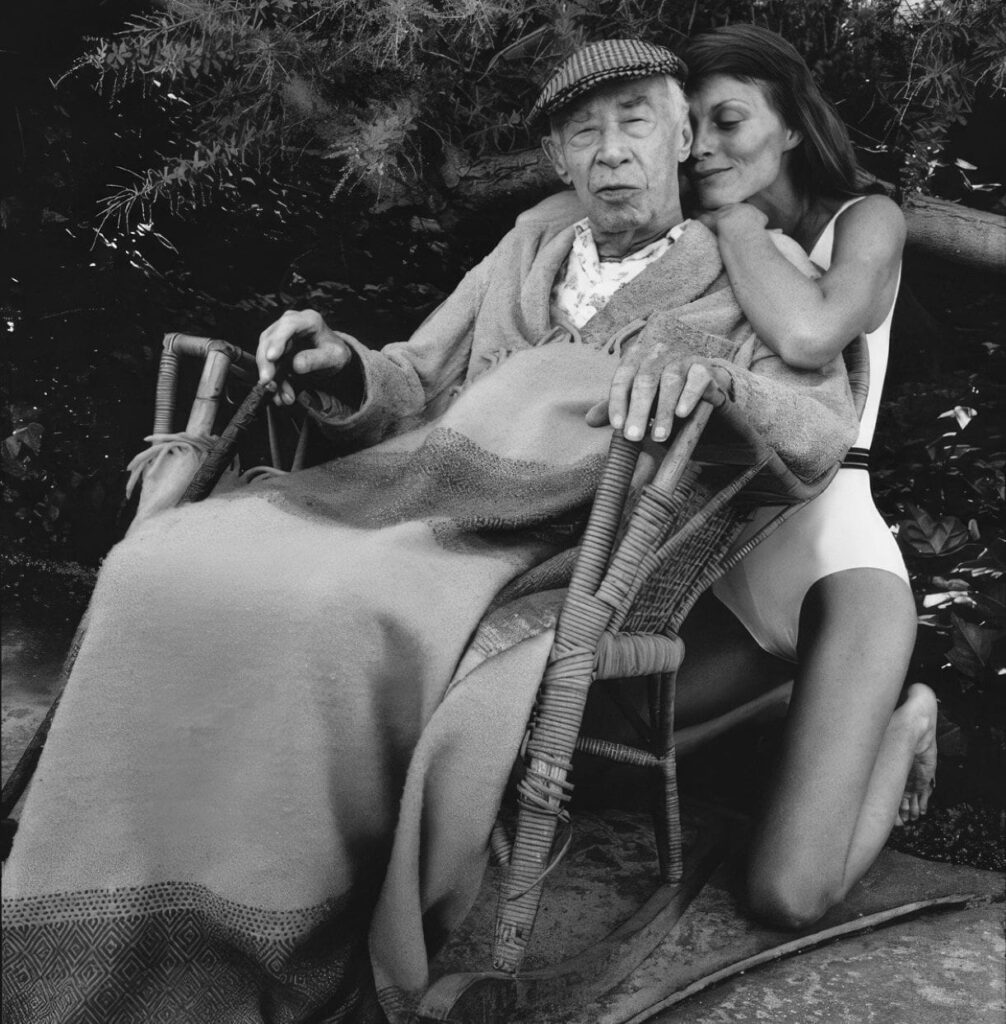

Raimu, Henry Miller

Raimu

IT IS as an American living in France, who has seen practically all the important films produced by Russia, Germany, France and America, that I write this tribute to Raimu whom I consider the most human figure on the screen today.

Though it seems that the French films have at last won the recognition which they deserve, in America, from the titles which I see discussed I realize that these films which my countrymen are beginning to appreciate, ten years too late, are by no means the best which the French have to offer.

America is always twenty to fifty years behind time in accepting the true genius of Europe. Even today, for example, they are still discovering, through their avant-garde reviews, such writers as Jean Cocteau and Leon Paul Fargue. Recently an American who came to visit me had the naïveté to ask me if I did not consider the author of Hommes de Bonne Volonté the Dos Passos of Europe!

The fundamental difference between the French and American films, as everybody knows, lies in the understanding of what is human. A French film, when it is good, is unsurpassable, not only because it is more true to life but because this conception of life strikes a deeper note than anything conceived by Russians, Germans, or Americans.

A fact often commented upon by foreigners is that French actors, male and female, are usually well advanced in years, usually quite unprepossessing, if not downright homely, and, when given the opportunity (which is not often enough), are capable of assuming the most diverse roles, including the comic as well as the tragic.

In the American films, on the other hand, it is highly noticeable that there is not one great serious actor, unless it be the clown, Charlie Chaplin. (Men like Paul Muni and Edward Robinson, capable in their way, are always actors rather than men.) Anything verging on the tragic, in the American film, quickens into melodrama and sticky sentimentality.

In the better French films (the poor ones are below every level!) there is always a sense of reality, of the tragicomedy of life. Where the French film fails is in the realm of imagination, of phantasy.

It is the inherent weakness of the French character, the blind spot which accounts perhaps for the popularity of such a feeble masterpiece, in literature, as Le Grand Meaulnes. Among the French, one often hears it said that the American film, even if bad, is at any rate amusing. They are never thoroughly bored by a bad American film—so they say, at least.

Myself, I am bored to tears often, even by the “great” American films. This attitude of the French is explicable only because they do not expect too much of anything American. A man would be an imbecile, for example, to be disappointed in a work of Maurice Dekobra’s. Somehow, much is expected of a good French film, even by the French.

In Raimu, whose rise I have watched now for several years, the French people, the soul quality, I might say, makes itself manifest. Raimu is the one truly human figure on the screen today, and whether he be considered a good actor or a bad one is relatively unimportant.

He represents something which is vitally missing in the cinema, and he represents it forcefully. To appreciate his contribution one has only to take a sidelong glance at his American counterpart, Wallace Beery.

The latter, together with Gary Cooper, represent the highest efforts of the American producers to give us a semblance of the human being and not the Hollywood figure in papier-mâché. But they are usually cast for adventure, for thrilling episodes, for action. Only once was Gary Cooper, for example, permitted to express anything like his real self—in Mr. Deeds Goes to Town.

Wallace Beery has never been given a role which would permit him to reveal his full stature—nor has Barbara Stanwyck, except for one film, Liliane, which was banned in America. To understand this deliberate deteriorization of character which Hollywood enforces one has only to reflect on what happens to the French actor whose services are impressed by Hollywood.

Any ordinary French film starring Charles Boyer or Daniele Darrieux, for example, seems infinitely better than the sensational ones created for them in America. What is the constant plaint of the French artist after his arrival in Hollywood? “They want to make us over!”

It is the American vice, the democratic disease which expresses its tyranny by reducing everything unique to the level of the herd. Think of “making over” the heroine of Mayerling! Think of what it would mean to make over a Gabin or a Jouvet!

I do not mean to imply by the foregoing that the French producers are animated only by lofty artistic ideals. I think, taking them by and large, that they are as guilty as the American producers of complicity in foisting upon the public anything and everything which will bring quick returns.

They are as bad as the French publishers who are deliberately, cold-bloodedly, ruining the taste for good literature by their shameless concentration on the till. They are as bad as the French politicians who, bar none, are the most corrupt in the world.

But there is something in the French character which, despite the lowest intentions, prevents them from completely betraying their heritage. The Frenchman is first and foremost a man. He is likeable often just because of his weaknesses, which are always thoroughly human, even if despicable.

As a rogue and a scoundrel he is more often than not misled by a perverted sense of reality which he calls realism. But even at his worst there always remains an area—of the soul, shall I say?—with which one can deal and hope for an ultimate understanding.

It is difficult for a Frenchman to wholly defeat the human being in himself. Race, tradition, culture—these speak out even when the mind has been traduced. And so, even with the worst motives, it often happens that a mediôcre French film offers something which the best films of other countries never take into account.

Study the faces of the American stars! Compare them with the French. At a glance one can spot the difference—the contrast between adolescence and maturity, between a fake idealism and a grim sense of reality, between puppets who will perform any insane stunt and individuals who cannot be trained to act like monkeys no matter what bait is held out to them. The American cannot help making an ass of himself, even when he is inspired; the Frenchman is always a human being, even when he caricatures himself.

The American ideal is youth—handsome, empty youth. Russia too idolizes youth, but what a difference between the two conceptions of youth! Russia is young in spirit, because the spirit is still vital; in America youth means simply athleticism, disrespect, gangsterism, or sickly idealism expressing itself through thinly disguised and badly digested social science theories acted out by idiots who are desperadoes at heart.

Think of the American idol, James Cagney; or of Robert Taylor, the matinee idol of the screen; or of Clark Gable, the symbol of American vigor and manliness! What do they bring to the screen besides good looks, a fast, pat lingo, the art of fisticuffs, or a suit of well-tailored clothes?

Think of Victor MacLaglen, for whose work in The Informer I have the highest admiration. Think, however, what it is America truly admires in him! They have made him the symbol of their own brutish nature.

Let us get back to the human, to Raimu. . . . One of the things which impresses me most about Raimu is his habit of going about in shirt sleeves and suspenders, his struggles to lace his boots or to tie his cravat.

He is always sweating (not perspiring!), always trying to unburden himself of his clothes, to give his body light and air. It is a quality which one almost never observes in an American actor. Raimu sweats, weeps, laughs, yells with pain.

Raimu flies into a rage, an unholy rage, in which he is not ashamed to strike his wife or son, if deserving of his wrath. Wrath! Here again is something which is usually absent from the American’s repertoire of emotions.

The wrath of Raimu is magnificent; there is something Biblical, something godlike about it. It springs up from that sense of justice which is never entirely stifled in the French and which, when roused, permits them to accomplish superhuman feats of strength and daring.

When the American strikes it is really a reflex action. (Hie Englishman, be it noted, seldom resorts to violence; when he is sufficiently goaded he simply opens up, like the oyster, and devours his adversary.

Yet the most sadistic picture I have ever seen, the only picture which I think should be banned, is the British production of Broken Blossom.) No, the American scarcely knows what anger is, nor joy, for that matter.

He oscillates between cold-blooded murder, as depicted by the gangsters or those who are punishing them, and a bright, hard gaiety devoid of all sensitivity, all respect and consideration for the personality of the other. He is quick to kill or to laugh, but both his laughter and his murderousness are empty.

The “fraicheur” which the French pretend to see in the impossible American farces is a hoax. The Americans are not young and fresh in spirit, but senile; their humor is hysterical, a reaction born of panic, of a refusal to look life in the face.

The way they throw their bodies around, the way they pummel one another, the way they destroy themselves and the objects which they have