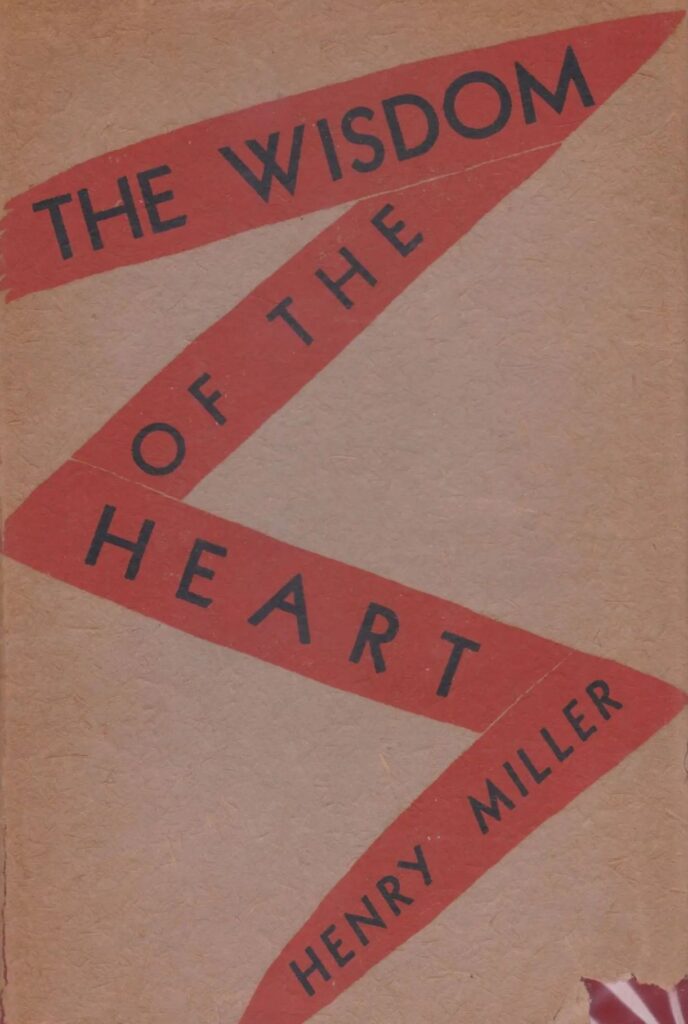

The Wisdom of the Heart, Henry Miller

Contents

Creative Death

Benno, The Wild Man from Borneo

Reflections on Writing

The Wisdom of the Heart

Raimu

The Cosmological Eye

The Philosopher Who Philosophizes

The Absolute Collective

The Enormous Womb

The Alcoholic Veteran with the Washboard Cranium

Mademoiselle Claude

Tribute To Blaise Cendrars

Into the Future

The Eye of Paris

Uterine Hunger

Seraphita

Balzac and His Double

Creative Death

“I DON’T WANT my Fate or Providence to treat me well. I am essentially a fighter.” It was towards the end of his life that Lawrence wrote this, but at the very threshold of his career he was saying: “We have to hate our immediate predecessors to get free of their authority.”

The men to whom he owed everything, the great spirits on whom he fed and nourished himself, whom he had to reject in order to assert his own power, his own vision, were they not like himself men who went to the source? Were they not all animated by that same idea which Lawrence voiced over and over again—that the sun itself will never become stale, nor the earth barren? Were they not, all of them, in their search for God, for that “clue which is missing inside men,” victims of the Holy Ghost?

Who were his predecessors? To whom, time and again before ridiculing and exposing them, did he acknowledge his indebtedness? Jesus certainly, and Nietzsche, and Whitman and Dostoievski. All the poets of life, the mystics, who in denouncing civilization contributed most heavily to the lie of civilization.

Lawrence was tremendously influenced by Dostoievski. Of all his forerunners, Jesus included, it was Dostoievski whom he had most difficulty in shaking off, in surpassing, in “transcending.” Lawrence had always looked upon the sun as the source of life, and the moon as the symbol of non-being. Life and Death—like a mariner he kept before him constantly these two poles.

“He who gets nearer the sun,” he said, “is leader, the aristocrat of aristocrats. Or, he who like Dostoievski, gets nearer the moon of our non-being.” With the in-betweens he had no concern.

“But the most powerful being,” he concludes, “is that which moves towards the as-yet-unknown blossom!” He saw man as a seasonal phenomenon, a moon that waxes and wanes, a seed that emerges out of primal darkness to return again therein. Life brief, transitory, eternally fixed between the two poles of being and non-being. Without the clue, without the revelation no life, but being sacrificed to existence. Immortality he interpreted as this futile wish for endless existence. To him this living death was the Purgatory in which man ceaselessly struggles.

Strange as it may seem today to say, the aim of life is to live, and to live means to be aware, joyously, drunkenly, serenely, divinely aware. In this state of god-like awareness one sings; in this realm the world exists as poem.

No why or wherefore, no direction, no goal, no striving, no evolving. Like the enigmatic Chinaman one is rapt by the everchanging spectacle of passing phenomena. This is the sublime, the a-moral state of the artist, he who lives only in the moment, the visionary moment of utter, far-seeing lucidity.

Such clear, icy sanity that it seems like madness. By the force and power of the artist’s vision the static, synthetic whole which is called the world is destroyed. The artist gives back to us a vital, singing universe, alive in all its parts.

In a way the artist is always acting against the time-destiny movement. He is always a-historical. He accepts Time absolutely, as Whitman says, in the sense that any way he rolls (with tail in mouth) is direction; in the sense that any moment, every moment, may be the all; for the artist there is nothing but the present, the eternal here and now, the expanding infinite moment which is flame and song.

And when he succeeds in establishing this criterion of passionate experience (which is what Lawrence meant by “obeying the Holy Ghost”) then, and only then, is he asserting his humanness.

Then only does he live out his pattern as Man. Obedient to every urge—without distinction of morality, ethics, law, custom, etc. He opens himself to all influences—everything nourishes him. Everything is gravy to him, including what he does not understand—particularly what he does not understand.

This final reality which the artist comes to recognize in his maturity is that symbolic paradise of the womb, that “China” which the psychologists place somewhere between the conscious and the unconscious, that pre-natal security and immortality and union with nature from which he must wrest his freedom. Each time he is spiritually born he dreams of the impossible, the miraculous, dreams he can break the wheel of life and death, avoid the struggle and the drama, the pain and the suffering of life.

His poem is the legend wherein he buries himself, wherein he relates of the mysteries of birth and death—his reality, his experience. He buries himself in his tomb of poem in order to achieve that immortality which is denied him as a physical being.

China is a projection into the spiritual domain of his biologic condition of non-being. To be is to have mortal shape, mortal conditions, to struggle, to evolve. Paradise is, like the dream of the Buddhists, a Nirvana where there is no more personality and hence no conflict. It is the expression of man’s wish to triumph over reality, over becoming. The artist’s dream of the impossible, the miraculous, is simply the resultant of his inability to adapt himself to reality.

He creates, therefore, a reality of his own—in the poem—a reality which is suitable to him, a reality in which he can live out his unconscious desires, wishes, dreams. The poem is the dream made flesh, in a two-fold sense: as work of art, and as life, which is a work of art. When man becomes fully conscious of his powers, his role, his destiny, he is an artist and he ceases his struggle with reality. He becomes a traitor to the human race.

He creates war because he has become permanently out of step with the rest of humanity. He sits on the door-step of his mother’s womb with his race memories and his incestuous longings and he refuses to budge. He lives out his dream of Paradise. He transmutes his real experience of life into spiritual equations.

He scorns the ordinary alphabet, which yields at most only a grammar of thought, and adopts the symbol, the metaphor, the ideograph. He writes Chinese. He creates an impossible world out of an incomprehensible language, a lie that enchants and enslaves men.

It is not that he is incapable of living. On the contrary, his zest for life is so powerful, so voracious that it forces him to kill himself over and over. He dies many times in order to live innumerable lives. In this way he wreaks his revenge upon life and works his power over men. He creates the legend of himself, the lie wherein he establishes himself as hero and god, the lie wherein he triumphs over life.

Perhaps one of the chief difficulties in wrestling with the personality of a creative individual lies in the powerful obscurity in which, wittingly or unwittingly, he lodges himself. In the case of a man like Lawrence we are dealing with one who glorified the obscurity, a man who raised to the highest that source and manifestation of all life, the body.

All efforts to clarify his doctrine involve a return to, and a renewed wrestling with, the eternal, fundamental problems which confronted him. He is forever bringing one back to the source, to the very heart of the cosmos, through a mystic labyrinth.

His work is altogether one of symbol and metaphor. Phoenix, Crown, Rainbow, Plumed Serpent, all these symbols center about the same obsessive idea: the resolution of two opposites in the form of a mystery. Despite his progression from one plane of conflict to another, from one problem of life to another, the symbolic character of his work remains constant and unchanged. He is a man of one idea: that life has a symbolic significance. Which is to say that life and art are one.

In his choice of the Rainbow, for example, one sees how he attempted to glorify the eternal hope in man, the illusion on which his justification as artist rests. In all his symbols, the Phoenix and the Crown particularly, for they were his earliest and most potent symbols, we observe that he was but giving concrete form to his real nature, his artist being. For the artist in man is the undying symbol of the union between his warring selves.

Life has to be given a meaning because of the obvious fact that it has no meaning. Something has to be created, as a healing and goading intervention, between life and death, because the conclusion that life points to is death and to that conclusive fact man instinctively and persistently shuts his eyes. The sense of mystery, which is at the bottom of all art, is the amalgam of all the nameless terrors which the cruel reality of death inspires. Death then has to be defeated—or disguised, or transmogrified.

But in the attempt to defeat death man has been inevitably obliged to defeat life, for the two are inextricably related. Life moves on to death, and to deny one is to deny the other. The stern sense of destiny which every creative individual reveals lies in this awareness of the goal, this acceptance of the goal, this moving on towards a fatality, one with the inscrutable forces that animate him and drive him on.

All history is the record of man’s signal failure to thwart his destiny—the