When all the souls had chosen they went to Lachesis, who sent with each of them their genius or attendant to fulfil their lot. He first of all brought them under the hand of Clotho, and drew them within the revolution of the spindle impelled by her hand; from her they were carried to Atropos, who made the threads irreversible; whence, without turning round, they passed beneath the throne of Necessity; and when they had all passed, they moved on in scorching heat to the plain of Forgetfulness and rested at evening by the river Unmindful, whose water could not be retained in any vessel; of this they had all to drink a certain quantity—some of them drank more than was required, and he who drank forgot all things. Er himself was prevented from drinking. When they had gone to rest, about the middle of the night there were thunderstorms and earthquakes, and suddenly they were all driven divers ways, shooting like stars to their birth. Concerning his return to the body, he only knew that awaking suddenly in the morning he found himself lying on the pyre.

Thus, Glaucon, the tale has been saved, and will be our salvation, if we believe that the soul is immortal, and hold fast to the heavenly way of Justice and Knowledge. So shall we pass undefiled over the river of Forgetfulness, and be dear to ourselves and to the Gods, and have a crown of reward and happiness both in this world and also in the millennial pilgrimage of the other.

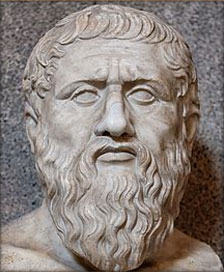

The Tenth Book of the Republic of Plato falls into two divisions: first, resuming an old thread which has been interrupted, Socrates assails the poets, who, now that the nature of the soul has been analyzed, are seen to be very far gone from the truth; and secondly, having shown the reality of the happiness of the just, he demands that appearance shall be restored to him, and then proceeds to prove the immortality of the soul. The argument, as in the Phaedo and Gorgias, is supplemented by the vision of a future life.

Why Plato, who was himself a poet, and whose dialogues are poems and dramas, should have been hostile to the poets as a class, and especially to the dramatic poets; why he should not have seen that truth may be embodied in verse as well as in prose, and that there are some indefinable lights and shadows of human life which can only be expressed in poetry—some elements of imagination which always entwine with reason; why he should have supposed epic verse to be inseparably associated with the impurities of the old Hellenic mythology; why he should try Homer and Hesiod by the unfair and prosaic test of utility,—are questions which have always been debated amongst students of Plato. Though unable to give a complete answer to them, we may show—first, that his views arose naturally out of the circumstances of his age; and secondly, we may elicit the truth as well as the error which is contained in them.

He is the enemy of the poets because poetry was declining in his own lifetime, and a theatrocracy, as he says in the Laws, had taken the place of an intellectual aristocracy. Euripides exhibited the last phase of the tragic drama, and in him Plato saw the friend and apologist of tyrants, and the Sophist of tragedy. The old comedy was almost extinct; the new had not yet arisen. Dramatic and lyric poetry, like every other branch of Greek literature, was falling under the power of rhetoric. There was no ‘second or third’ to Aeschylus and Sophocles in the generation which followed them. Aristophanes, in one of his later comedies (Frogs), speaks of ‘thousands of tragedy-making prattlers,’ whose attempts at poetry he compares to the chirping of swallows; ‘their garrulity went far beyond Euripides,’—‘they appeared once upon the stage, and there was an end of them.’ To a man of genius who had a real appreciation of the godlike Aeschylus and the noble and gentle Sophocles, though disagreeing with some parts of their ‘theology’ (Rep.), these ‘minor poets’ must have been contemptible and intolerable. There is no feeling stronger in the dialogues of Plato than a sense of the decline and decay both in literature and in politics which marked his own age. Nor can he have been expected to look with favour on the licence of Aristophanes, now at the end of his career, who had begun by satirizing Socrates in the Clouds, and in a similar spirit forty years afterwards had satirized the founders of ideal commonwealths in his Eccleziazusae, or Female Parliament (Laws).

There were other reasons for the antagonism of Plato to poetry. The profession of an actor was regarded by him as a degradation of human nature, for ‘one man in his life’ cannot ‘play many parts;’ the characters which the actor performs seem to destroy his own character, and to leave nothing which can be truly called himself. Neither can any man live his life and act it. The actor is the slave of his art, not the master of it. Taking this view Plato is more decided in his expulsion of the dramatic than of the epic poets, though he must have known that the Greek tragedians afforded noble lessons and examples of virtue and patriotism, to which nothing in Homer can be compared. But great dramatic or even great rhetorical power is hardly consistent with firmness or strength of mind, and dramatic talent is often incidentally associated with a weak or dissolute character.

In the Tenth Book Plato introduces a new series of objections. First, he says that the poet or painter is an imitator, and in the third degree removed from the truth. His creations are not tested by rule and measure; they are only appearances. In modern times we should say that art is not merely imitation, but rather the expression of the ideal in forms of sense. Even adopting the humble image of Plato, from which his argument derives a colour, we should maintain that the artist may ennoble the bed which he paints by the folds of the drapery, or by the feeling of home which he introduces; and there have been modern painters who have imparted such an ideal interest to a blacksmith’s or a carpenter’s shop. The eye or mind which feels as well as sees can give dignity and pathos to a ruined mill, or a straw-built shed (Rembrandt), to the hull of a vessel ‘going to its last home’ (Turner). Still more would this apply to the greatest works of art, which seem to be the visible embodiment of the divine. Had Plato been asked whether the Zeus or Athene of Pheidias was the imitation of an imitation only, would he not have been compelled to admit that something more was to be found in them than in the form of any mortal; and that the rule of proportion to which they conformed was ‘higher far than any geometry or arithmetic could express?’ (Statesman.)

Again, Plato objects to the imitative arts that they