Art cannot claim to be on a level with philosophy or religion, and may often corrupt them. It is possible to conceive a mental state in which all artistic representations are regarded as a false and imperfect expression, either of the religious ideal or of the philosophical ideal. The fairest forms may be revolting in certain moods of mind, as is proved by the fact that the Mahometans, and many sects of Christians, have renounced the use of pictures and images. The beginning of a great religion, whether Christian or Gentile, has not been ‘wood or stone,’ but a spirit moving in the hearts of men. The disciples have met in a large upper room or in ‘holes and caves of the earth’; in the second or third generation, they have had mosques, temples, churches, monasteries. And the revival or reform of religions, like the first revelation of them, has come from within and has generally disregarded external ceremonies and accompaniments.

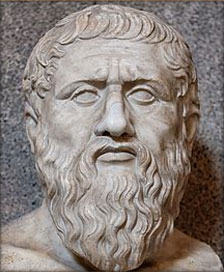

But poetry and art may also be the expression of the highest truth and the purest sentiment. Plato himself seems to waver between two opposite views—when, as in the third Book, he insists that youth should be brought up amid wholesome imagery; and again in Book X, when he banishes the poets from his Republic. Admitting that the arts, which some of us almost deify, have fallen short of their higher aim, we must admit on the other hand that to banish imagination wholly would be suicidal as well as impossible. For nature too is a form of art; and a breath of the fresh air or a single glance at the varying landscape would in an instant revive and reillumine the extinguished spark of poetry in the human breast. In the lower stages of civilization imagination more than reason distinguishes man from the animals; and to banish art would be to banish thought, to banish language, to banish the expression of all truth. No religion is wholly devoid of external forms; even the Mahometan who renounces the use of pictures and images has a temple in which he worships the Most High, as solemn and beautiful as any Greek or Christian building. Feeling too and thought are not really opposed; for he who thinks must feel before he can execute. And the highest thoughts, when they become familiarized to us, are always tending to pass into the form of feeling.

Plato does not seriously intend to expel poets from life and society. But he feels strongly the unreality of their writings; he is protesting against the degeneracy of poetry in his own day as we might protest against the want of serious purpose in modern fiction, against the unseemliness or extravagance of some of our poets or novelists, against the time-serving of preachers or public writers, against the regardlessness of truth which to the eye of the philosopher seems to characterize the greater part of the world. For we too have reason to complain that our poets and novelists ‘paint inferior truth’ and ‘are concerned with the inferior part of the soul’; that the readers of them become what they read and are injuriously affected by them. And we look in vain for that healthy atmosphere of which Plato speaks,—‘the beauty which meets the sense like a breeze and imperceptibly draws the soul, even in childhood, into harmony with the beauty of reason.’

For there might be a poetry which would be the hymn of divine perfection, the harmony of goodness and truth among men: a strain which should renew the youth of the world, and bring back the ages in which the poet was man’s only teacher and best friend,—which would find materials in the living present as well as in the romance of the past, and might subdue to the fairest forms of speech and verse the intractable materials of modern civilisation,—which might elicit the simple principles, or, as Plato would have called them, the essential forms, of truth and justice out of the variety of opinion and the complexity of modern society,—which would preserve all the good of each generation and leave the bad unsung,—which should be based not on vain longings or faint imaginings, but on a clear insight into the nature of man. Then the tale of love might begin again in poetry or prose, two in one, united in the pursuit of knowledge, or the service of God and man; and feelings of love might still be the incentive to great thoughts and heroic deeds as in the days of Dante or Petrarch; and many types of manly and womanly beauty might appear among us, rising above the ordinary level of humanity, and many lives which were like poems (Laws), be not only written, but lived by us. A few such strains have been heard among men in the tragedies of Aeschylus and Sophocles, whom Plato quotes, not, as Homer is quoted by him, in irony, but with deep and serious approval,—in the poetry of Milton and Wordsworth, and in passages of other English poets,—first and above all in the Hebrew prophets and psalmists. Shakespeare has taught us how great men should speak and act; he has drawn characters of a wonderful purity and depth; he has ennobled the human mind, but, like Homer (Rep.), he ‘has left no way of life.’ The next greatest poet of modern times, Goethe, is concerned with ‘a lower degree of truth’; he paints the world as a stage on which ‘all the men and women are merely players’; he cultivates life as an art, but he furnishes no ideals of truth and action. The poet may rebel against any attempt to set limits to his fancy; and he may argue truly that moralizing in verse is not poetry. Possibly, like Mephistopheles in Faust, he may retaliate on his adversaries. But the philosopher will still be justified in asking, ‘How may the heavenly gift of poesy be devoted to the good of mankind?’

Returning to Plato, we may observe that a similar mixture of truth and error appears in other parts of the argument. He is aware of the absurdity of mankind framing their whole lives according to Homer; just as in the Phaedrus he intimates the absurdity of interpreting mythology upon rational principles; both these were the modern tendencies of his own age, which he deservedly ridicules. On the other hand, his argument that Homer, if he had been able to teach mankind anything worth knowing, would not have been allowed by them to go about begging as a rhapsodist, is both false and contrary to the spirit of Plato (Rep.). It may be compared with those other paradoxes of the Gorgias, that ‘No statesman was ever unjustly put to death by the city of which he was the head’; and that ‘No Sophist was ever defrauded by his pupils’ (Gorg.)…

The argument for immortality seems to rest on the absolute dualism of soul and body. Admitting the existence of the soul, we know of no force which is able to put an end to her. Vice is her own proper evil; and if she cannot be destroyed by that, she cannot be destroyed by any other. Yet Plato has acknowledged that the soul may be so overgrown by the incrustations of earth as to lose her original form; and in the Timaeus he recognizes more strongly than in the Republic the influence which the body has over the mind, denying even the voluntariness of human actions, on the ground that they proceed from physical states (Tim.). In the Republic, as elsewhere, he wavers between the original soul which has to be restored, and the character which is developed by training and education…

The vision of another world is ascribed to Er, the son of Armenius, who is said by Clement of Alexandria to have been Zoroaster. The tale has certainly an oriental character, and may be compared with the pilgrimages of the soul in the Zend Avesta (Haug, Avesta). But no trace of acquaintance with Zoroaster is found elsewhere in Plato’s writings, and there is no reason for giving him the name of Er the Pamphylian. The philosophy of Heracleitus cannot be shown to be borrowed from Zoroaster, and still less the myths of Plato.

The local arrangement of the vision is less distinct than that of the Phaedrus and Phaedo. Astronomy is mingled with symbolism and mythology; the great sphere of heaven is represented under the symbol of a cylinder or box, containing the seven orbits of the planets and the fixed stars; this is suspended from an axis or spindle which turns on the knees of Necessity; the revolutions of the seven orbits contained in the cylinder are guided by the fates, and their harmonious motion produces the music of the spheres. Through the innermost or eighth of these, which is the moon, is passed the spindle; but it is doubtful whether this is the continuation of the column of light, from which the pilgrims contemplate the heavens; the words of Plato imply that they are connected, but not the same. The column itself is clearly not of adamant. The spindle (which is of adamant) is fastened to the ends of the chains which extend to the middle of the column of light—this column is said to hold together the heaven; but whether it hangs from the spindle, or is at right angles to it, is not explained. The cylinder containing the orbits of the stars