To the doubts and queries raised by these ‘social reformers’ respecting the relation of the sexes and the moral nature of man, there is a sufficient answer, if any is needed. The difference about them and us is really one of fact. They are speaking of man as they wish or fancy him to be, but we are speaking of him as he is. They isolate the animal part of his nature; we regard him as a creature having many sides, or aspects, moving between good and evil, striving to rise above himself and to become ‘a little lower than the angels.’ We also, to use a Platonic formula, are not ignorant of the dissatisfactions and incompatibilities of family life, of the meannesses of trade, of the flatteries of one class of society by another, of the impediments which the family throws in the way of lofty aims and aspirations. But we are conscious that there are evils and dangers in the background greater still, which are not appreciated, because they are either concealed or suppressed. What a condition of man would that be, in which human passions were controlled by no authority, divine or human, in which there was no shame or decency, no higher affection overcoming or sanctifying the natural instincts, but simply a rule of health! Is it for this that we are asked to throw away the civilization which is the growth of ages?

For strength and health are not the only qualities to be desired; there are the more important considerations of mind and character and soul. We know how human nature may be degraded; we do not know how by artificial means any improvement in the breed can be effected. The problem is a complex one, for if we go back only four steps (and these at least enter into the composition of a child), there are commonly thirty progenitors to be taken into account. Many curious facts, rarely admitting of proof, are told us respecting the inheritance of disease or character from a remote ancestor. We can trace the physical resemblances of parents and children in the same family—

‘Sic oculos, sic ille manus, sic ora ferebat’;

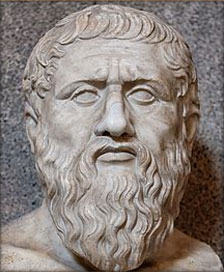

but scarcely less often the differences which distinguish children both from their parents and from one another. We are told of similar mental peculiarities running in families, and again of a tendency, as in the animals, to revert to a common or original stock. But we have a difficulty in distinguishing what is a true inheritance of genius or other qualities, and what is mere imitation or the result of similar circumstances. Great men and great women have rarely had great fathers and mothers. Nothing that we know of in the circumstances of their birth or lineage will explain their appearance. Of the English poets of the last and two preceding centuries scarcely a descendant remains,—none have ever been distinguished. So deeply has nature hidden her secret, and so ridiculous is the fancy which has been entertained by some that we might in time by suitable marriage arrangements or, as Plato would have said, ‘by an ingenious system of lots,’ produce a Shakespeare or a Milton. Even supposing that we could breed men having the tenacity of bulldogs, or, like the Spartans, ‘lacking the wit to run away in battle,’ would the world be any the better? Many of the noblest specimens of the human race have been among the weakest physically. Tyrtaeus or Aesop, or our own Newton, would have been exposed at Sparta; and some of the fairest and strongest men and women have been among the wickedest and worst. Not by the Platonic device of uniting the strong and fair with the strong and fair, regardless of sentiment and morality, nor yet by his other device of combining dissimilar natures (Statesman), have mankind gradually passed from the brutality and licentiousness of primitive marriage to marriage Christian and civilized.

Few persons would deny that we bring into the world an inheritance of mental and physical qualities derived first from our parents, or through them from some remoter ancestor, secondly from our race, thirdly from the general condition of mankind into which we are born. Nothing is commoner than the remark, that ‘So and so is like his father or his uncle’; and an aged person may not unfrequently note a resemblance in a youth to a long-forgotten ancestor, observing that ‘Nature sometimes skips a generation.’ It may be true also, that if we knew more about our ancestors, these similarities would be even more striking to us. Admitting the facts which are thus described in a popular way, we may however remark that there is no method of difference by which they can be defined or estimated, and that they constitute only a small part of each individual. The doctrine of heredity may seem to take out of our hands the conduct of our own lives, but it is the idea, not the fact, which is really terrible to us. For what we have received from our ancestors is only a fraction of what we are, or may become. The knowledge that drunkenness or insanity has been prevalent in a family may be the best safeguard against their recurrence in a future generation. The parent will be most awake to the vices or diseases in his child of which he is most sensible within himself. The whole of life may be directed to their prevention or cure. The traces of consumption may become fainter, or be wholly effaced: the inherent tendency to vice or crime may be eradicated. And so heredity, from being a curse, may become a blessing. We acknowledge that in the matter of our birth, as in our nature generally, there are previous circumstances which affect us. But upon this platform of circumstances or within this wall of necessity, we have still the power of creating a life for ourselves by the informing energy of the human will.

There is another aspect of the marriage question to which Plato is a stranger. All the children born in his state are foundlings. It never occurred to him that the greater part of them, according to universal experience, would have perished. For children can only be brought up in families. There is a subtle sympathy between the mother and the child which cannot be supplied by other mothers, or by ‘strong nurses one or more’ (Laws). If Plato’s ‘pen’ was as fatal as the Creches of Paris, or the foundling hospital of Dublin, more than nine-tenths of his children would have perished. There would have been no need to expose or put out of the way the weaklier children, for they would have died of themselves. So emphatically does nature protest against the destruction of the family.

What Plato had heard or seen of Sparta was applied by him in a mistaken way to his ideal commonwealth. He probably observed that both the Spartan men and women were superior in form and strength to the other Greeks; and this superiority he was disposed to attribute to the laws and customs relating to marriage. He did not consider that the desire of a noble offspring was a passion among the Spartans, or that their physical superiority was to be attributed chiefly, not to their marriage customs, but to their temperance and training. He did not reflect that Sparta was great, not in consequence of the relaxation of morality, but in spite of it, by virtue of a political principle stronger far than existed in any other Grecian state. Least of all did he observe