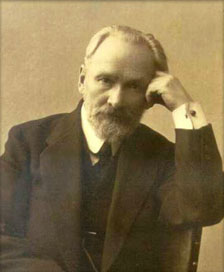

Vasily Vasilyevich Rozanov (April 20, 1856, Vetluga, Kostroma Governorate – February 5, 1919, Sergiev Posad) – Russian religious philosopher, literary critic and publicist. Together with P. D. Pervov, he completed the first Russian translation of Aristotle’s Metaphysics.

Biography

Vasily Rozanov was born on April 20 (May 2), 1856 in the city of Vetluga, Kostroma Governorate, into a large (8 children) family of the collegiate secretary, official of the forestry department Vasily Fedorovich Rozanov (1822-1861) and Nadezhda Ivanovna (from the impoverished noble family of Shishkin, 1826-1870). After the death of his father, the family moved to his mother’s homeland, to Kostroma. From 1868 to 1870, Rozanov studied at the Kostroma gymnasium. Having lost his parents early, he was raised by his older brother Nikolai (1847-1894). In 1870, he moved with his brothers to Simbirsk, where Nikolai taught at the gymnasium for some time. Rozanov himself later recalled:

There is no doubt that I would have completely perished if my older brother Nikolai, who by that time had graduated from Kazan University, had not “picked me up”. He gave me all the means of education and, in a word, was a father.

The wife of his older brother, Alexandra Stepanovna Troitskaya, the daughter of a Nizhny Novgorod teacher, replaced his mother. In Simbirsk, Rozanov was a regular reader at the N. M. Karamzin public library. Simbirsk became Rozanov’s “spiritual homeland” (“I came to Simbirsk with nothing… I left it with everything…”). He studied at the Simbirsk gymnasium for two years, and in 1872 he moved to Nizhny Novgorod. Here in 1878 he graduated from the gymnasium and in the same year entered the historical and philological faculty of the Imperial Moscow University, where he attended lectures by S. M. Solovyov, V. O. Klyuchevsky, F. E. Korsh and others. By his own admission, Rozanov “became a lover of history, archeology, a lover of the “former” at the university; became a conservative.” During his studies, he wrote several scientific student papers: a historical one – “Charles V, his personality and attitude to the main issues of the time”, which received the highest mark from Professor V. I. Gerier; a logic one – “The Foundation of Behavior”, for which he received the N. V. Isakov Prize. In his fourth year, he was awarded a scholarship named after A. S. Khomyakov, but the topic of the essay is unknown. In 1880, 24-year-old Vasily Rozanov married 40-year-old A. P. Suslova, who had been in a close relationship with F. M. Dostoevsky in 1861-1866

After University

After graduating from the university in 1882, he refused to take the exam for a master’s degree, deciding to engage in free creativity. In 1882-1893, he taught at the gymnasiums of Bryansk (1882-1887), Yelets (1887-1891), Bely (1891-1893), Vyazma. His first book, “On Understanding. An Experiment in Studying the Nature, Boundaries, and Internal Structure of Science as Integral Knowledge” (1886), was one of the versions of the Hegelian justification of science, but was not successful. That same year, Suslova left Rozanov, refusing (and then refusing for another twenty years) to go for an official divorce. Rozanov’s literary and philosophical essay “The Legend of the Grand Inquisitor F. M. Dostoevsky” (1891) gained great fame, which laid the foundation for the subsequent interpretation of F. M. Dostoevsky as a religious thinker by N. A. Berdyaev, S. N. Bulgakov and other thinkers. Later, Rozanov became close to the writer as a participant in religious and philosophical meetings (1901-1903). In 1900, Merezhkovsky, Minsky, Gippius and Rozanov founded a religious and philosophical society. From the late 1890s, Rozanov became a well-known journalist of the late Slavophile persuasion, worked for the magazines “Russian Herald” and “Russian Review”, and was published in the newspaper “New Time”. Second marriage

In 1891, Rozanov secretly married Varvara Dmitrievna Butyagina (1864-1923), the widow of a priest and teacher at the Yelets Gymnasium.

As a teacher at the Yelets Gymnasium, Rozanov and his friend Pervov made the first translation of Aristotle’s Metaphysics from Greek in Russia.

The philosopher’s disagreement with the organization of school education in Russia is expressed in the articles “Twilight of Enlightenment” (1893) and “Aphorisms and Observations” (1894). In sympathetic tones, he described the unrest during the revolution of 1905-1907 in the book “When the Bosses Left” (1910). The collections “Religion and Culture” (1899) and “Nature and History” (1900) were Rozanov’s attempts to find a solution to social and ideological problems in church religiosity. However, his attitude toward the Orthodox Church (Around the Church Walls, vol. 1-2, 1906) remained contradictory. The book The Family Question in Russia (vol. 1-2, 1903) is devoted to the church’s attitude toward the problems of family and sexual relations. In his works The Dark Face. The Metaphysics of Christianity (1911) and People of the Moonlight (1911), Rozanov finally diverges from Christianity on issues of gender (contrasting the Old Testament, as an affirmation of the life of the flesh, with the New).

Break with the Religious-Philosophical Society

Rozanov’s articles on the Beilis affair (1911) led to a conflict with the Religious-Philosophical Society, of which the philosopher was a member. The society, which recognized the Beilis trial as “an insult to the entire Russian people,” called on Rozanov to leave its membership, which he soon did.

His later books – “Solitary” (1912), “Mortal” (1913), and “Fallen Leaves” (parts 1-2, 1913-1915) – are a collection of disparate essayistic sketches, fleeting speculations, diary entries, and internal dialogues, united by mood. There is an opinion that at this time the philosopher was experiencing a deep spiritual crisis that could not be resolved in the unconditional acceptance of Christian dogmas, to which Rozanov aspired; Following this view, the result of Rozanov’s thought can be considered pessimism and “existential” subjective idealism in the spirit of Søren Kierkegaard (distinguished, however, by the cult of individuality, expressing itself in the element of sex). Subject to this pessimism, in the outlines of “The Apocalypse of Our Time” (issues 1-10, from November 1917 to October 1918) Rozanov accepted the inevitability of a revolutionary catastrophe, considering it a tragic end to Russian history. In September 1917, he wrote:

I never thought that the Tsar was so necessary for me: but now he is gone – and for me, as there is no Russia. Absolutely not, and for me, in a dream, all my literary activity is not needed. I simply do not want it to be.

Rozanov’s views and works drew criticism from both revolutionary Marxists and the liberal camp of the Russian intelligentsia.

Moving to Sergiev Posad

In September 1917, the Rozanovs moved from hungry Petrograd to Sergiev Posad and settled in three rooms of the house of a teacher at the Vifanskaya Theological Seminary (the philosopher Father Pavel Florensky chose this housing for them). Before his death, Rozanov openly begged, went hungry, and at the end of 1918, he addressed a tragic request from the pages of his “Apocalypse”:

To the reader, if he is a friend. – In this terrible, amazing year, from many people, both familiar and completely unknown to me, I received, by some guess of the heart, help both in money and in food. And I cannot hide the fact that without such help I could not, would not have been able to survive this year. <…> For the help – great gratitude; and tears more than once moistened my eyes and soul. “Someone remembers, someone thinks, someone guessed.” <…> I am tired. I can’t. 2-3 handfuls of flour, 2-3 handfuls of cereal, five hard-baked eggs can often save my day. <…> Save, reader, your writer, and something final dawns on me in the last days of my life. V. R. Sergiev Posad, Moscow province, Krasyukovka, Polevaya street, house of priest Belyaev.

V. V. Rozanov died on February 5, 1919 and was buried on the north side of the Church of the Gethsemane Chernigov Skete in Sergiev Posad.

Family

V. V. Rozanov and V. D. Butyagina had four daughters and one son:

Daughter – Vereshchagina-Rozanova Nadezhda Vasilievna (1900-1956), artist, illustrator, wife of the artist Mikhail Ks. Sokolov. Daughter – Varvara, was married to the writer Vladimir Gordin.

Personality and creativity of Rozanov

Rozanov’s creativity and views cause very contradictory assessments. This is explained by his deliberate gravitation towards extremes, and the characteristic ambivalence of his thinking. “On a subject, one must have exactly 1000 points of view. These are the “coordinates of reality”, and reality is only captured through 1000.” Such a “theory of knowledge” really demonstrated the extraordinary possibilities of his, Rozanov’s, specific vision of the world. An example of this approach is that Rozanov considered it not only possible, but also necessary to cover the revolutionary events of 1905-1907 from various positions – speaking in Novoye Vremya under his own name as a monarchist and Black Hundred member, under the pseudonym V. Varvarin he expressed a left-liberal, populist, and sometimes even social democratic point of view in other publications.

Simbirsk was Rozanov’s “spiritual” homeland. He described his adolescent life here vividly, with great memory of events and the most subtle movements of the soul. Rozanov’s biography is based on three foundations. These are his three homelands: “physical” (Kostroma), “spiritual” (Simbirsk) and, later, “moral” (Yelets). Rozanov entered literature as an already formed personality. His more than thirty-year path in literature (1886-1918) was a continuous and gradual unfolding of talent and the revelation of genius. Rozanov changed themes, even changed the problems, but the personality of the creator remained intact. The conditions of his life (and they were no easier than those of his famous Volga compatriot Maxim Gorky), nihilistic upbringing and passionate youthful desire for public service prepared Rozanov for the path of a democratic activist. He could have become one of the spokesmen for social protest. However, his youthful “revolution” changed his biography radically, and Rozanov found his historical face in other spiritual areas. Rozanov became a commentator. With the exception of a few books (“Solitary”, “Fallen Leaves”, “Apocalypse of Our Time”), Rozanov’s vast legacy, as a rule, was written about some phenomena or events. Researchers note Rozanov’s egocentrism. The first editions of Rozanov’s “fallen leaves” books – “Solitary”, and then “Fallen Leaves”, which soon entered the golden fund of Russian literature, were perceived with bewilderment and confusion. Not a single positive review in print, except for a furious rebuff to a man who declared on the pages of a printed book: “I am not such a scoundrel as to think about morality.”

Rozanov is one of the Russian writers who happily experienced the love of readers, their unwavering devotion. This is evident from the responses of particularly sensitive readers of “The Solitary”, although expressed intimately, in letters. An example is the capacious response of M. O. Gershenzon:

Amazing Vasily Vasilyevich, three hours ago I received your book, and now I have read it. There is no other like it in the world – so that the heart trembles before the eyes without a shell, and the style is the same, not enveloping, but as if not existing, so that in it, as in pure water, everything is visible. This is your most needed book, because, as far as you are unique, you are fully expressed in it, and also because it is the key to all your writings and life. Abyss and lawlessness – that’s what’s in it; it’s even incomprehensible how you managed to not put on a system, a scheme, had the ancient courage to remain naked-spiritual, as your mother gave birth to you – and how you had enough courage in the 20th century, where everyone goes around dressed in a system, in consistency, in proof, to tell out loud and publicly your nakedness. Of course, in essence everyone is naked, but partly they themselves do not know it and in any case they cover themselves up outwardly. Yes, without this it would be impossible to live; if everyone wanted to live as they are, there would be no life. But you are not like everyone else, you really have the right to be completely yourself; I knew this before this book, and therefore I never measured you by the yardstick of morality or consistency, and therefore “forgiving”, if I can say this word here, I simply did not impute to you your writings, which are bad for me: the elements, and the law of the elements is lawlessness. Philosophy

Rozanov’s philosophy is part of the general Russian literary and philosophical circle, but the peculiarities of his existence in this context distinguish his figure and allow us to speak of him as an atypical representative. Being at the center of the development of Russian social thought in the early 20th century, Rozanov conducted an active dialogue with many philosophers, writers, poets, and critics. Many of his works were an ideological, meaningful reaction to individual judgments, thoughts, and works by Berdyaev, V. S. Solovyov, Blok, Merezhkovsky, and others, and contained detailed criticism of these opinions from the standpoint of his own worldview. The problems that occupied Rozanov’s thoughts were associated with moral and ethical, religious and ideological oppositions – metaphysics and Christianity, eroticism and metaphysics, Orthodoxy and nihilism, ethical nihilism and apology for the family. In each of them, Rozanov sought ways to remove contradictions, to such a scheme of their interactions, in which individual parts of the opposition become different manifestations of the same problems in human existence.

One of the interpretations of Rozanov’s philosophy is interesting, namely as the philosophy of the “little religious man”. The subject of his research is the vicissitudes of the “little religious man” alone with religion, such a wealth of material indicating the seriousness of questions of faith, their complexity. The grandeur of the tasks that the religious life of his era poses to Rozanov is only partly connected with the Church. The Church is not subject to critical assessment. A person remains alone with himself, bypassing the institutions and regulations that unite people, give them common tasks. When the question is posed in this way, the problem arises by itself, without the additional participation of the thinker. Religion by definition is unification, gathering together, etc. However, the concept of “individual religion” leads to a contradiction. However, if it is interpreted in such a way that within the framework of his individuality a religious person seeks his own way of connection and unification with others, then everything falls into place, everything acquires meaning and potential for research. This is what V. Rozanov uses.

Journalism

Researchers note the unusual genre of Rozanov’s writings, which eludes strict definition, but which has become firmly established in his journalistic work, implying a constant, as direct and at the same time expressive reaction to the burning issues of the day, and oriented towards Rozanov’s reference book, Dostoevsky’s Diary of a Writer.

In the published works “Solitary” (1912), “Mortal” (1913), “Fallen Leaves” (box 1 – 1913; box 2 – 1915) and the proposed collections “Sakharna”, “Posle Sakharna” (written following a vacation in the Bessarabian village of Sakharna, now Moldova), “Fleeting” and “The Last Leaves” the author attempts to reproduce the process of “understanding” in all its intriguing and complex pettiness and lively facial expressions of oral speech – a process merged with everyday life and contributing to mental self-determination. This genre turned out to be the most adequate to Rozanov’s thought, which always strove to become an experience; and his last work, an attempt to comprehend and thereby somehow humanize the revolutionary collapse of Russian history and its universal resonance, acquired a proven genre form. His “Apocalypse of Our Time” was published in an incredible two thousand copies in Bolshevik Russia from November 1917 to October 1918 (ten issues).

Religion in Rozanov’s Work

Rozanov wrote about himself:

I belong to that breed of “eternal self-expositor”, who in criticism are like a fish on land and even in a frying pan.” And he admitted: “Whatever I did, whatever I said or wrote, directly or especially indirectly, I spoke and thought, in fact, only about God: so that He occupied me entirely, without any remainder, at the same time somehow leaving my thought free and energetic in relation to other topics.

Rozanov believed that all other religions became individual, and Christianity became personal. It has become the business of every person to choose, that is, to exercise freedom, but not faith in the sense of quality and confession – this issue was resolved 2000 years ago, but in the sense of the quality of a person’s rootedness in a common faith. Rozanov is convinced that this process of churching cannot occur mechanically, through the passive acceptance of the sacrament of holy baptism. There must be active faith, there must be deeds of faith, and here the conviction is born that a person is not obliged to put up with the fact that he does not understand something in the real process of life, that everything that concerns his life acquires the quality of religiosity.

According to Rozanov, the attitude to God and to the Church is determined by conscience. Conscience distinguishes in a person the subjective and the objective, the individual and the personal, the essential, the main and the secondary. He writes: “It is necessary to distinguish two sides in the dispute about conscience:

1) its attitude to God;

2) its attitude to the Church.

God, according to Christian teaching, is a Personal infinite spirit. Everyone will understand at first glance that the attitude towards the Person is somewhat different than towards the order of things, towards the system of things. No one will say decisively that the Church is personal: on the contrary, the person in it, for example, any hierarch, deeply submits to a certain bequeathed and general order.”

The theme of gender

The central philosophical theme in the work of the mature Rozanov was his metaphysics of gender. In 1898, in one of his letters, he formulated his understanding of gender: “Gender in man is not an organ or a function, not flesh or physiology, but a creative entity… It is indefinable and incomprehensible to reason: but it Is and everything that exists is from It and from It.” The incomprehensibility of gender in no way means its unreality. On the contrary, gender, according to Rozanov, is the most real thing in this world and remains an insoluble riddle to the same extent that the meaning of being itself is inaccessible to reason. “Everyone instinctively feels that the riddle of being is actually the riddle of being being born, that is, that this is the riddle of gender being born.” In Rozanov’s metaphysics, man, united in his spiritual and physical life, is connected with Logos, but this connection takes place not in the light of universal reason, but in the most intimate, “night” sphere of human existence: in the sphere of sexual love.

The Jewish theme in Rozanov’s works

The Jewish theme occupied an important place in the works of Vasily Rozanov. This was connected with the foundations of Rozanov’s worldview – mystical pansexualism, religious worship of the life-giving power of sex, affirmation of the sanctity of marriage and childbearing. Denying Christian asceticism, monasticism and celibacy, Rozanov found religious sanctification of sex, family, conception and birth in the Old Testament. But his anti-Christian rebellion was pacified by his organic conservatism, sincere love for Russian “everyday confession”, for the family virtues of the Orthodox clergy, for the traditionally sanctified forms of Russian statehood. This is where the elements of Rozanov’s open anti-Semitism, which so confused and outraged many of his contemporaries, came from.

According to the Electronic Jewish Encyclopedia, Rozanov’s statements sometimes had an openly anti-Semitic character. Thus, in Rozanov’s work “Jewish Secret Writing” (1913) there is the following fragment:

“Just look at his gait: a Jew is walking down the street, stooped, old, dirty. Lapsedak, sidelocks; he doesn’t look like anyone else in the world! No one wants to shake his hand. “He smells of garlic”, and not just garlic. A Jew “smells bad”. Some kind of universal “indecent place”… Walks with some kind of indirect, unopen gait… A coward, timid… The Christian looks after him, and he blurts out:

— Ugh, disgusting, and why can’t I do without you?

Universal: “why can’t I do without you?”…” However, when assessing Rozanov’s views, one should also take into account his deliberate inclination toward extremes, and the characteristic ambivalence of his thinking. He managed to become known as both a Judeophile and a Judeophobe.

Rozanov himself denies anti-Semitism in his work. In a letter to M. O. Gershenzon he writes: “I, my dear sir, do not suffer from anti-Semitism… As for the Jews, … I somehow and for some reason love the ‘Jew with sidelocks’ both physiologically (almost sexually) and artistically, and secretly, in society, I always spy on them and admire them.” During the Beilis affair, Rozanov published numerous articles: “Andryusha Yushchinsky” (1913), “Fear and Excitement of the Jews” (1913), “An Open Letter to S. K. Efron” (1913), “On One Method of Defending Jewry” (1913), “The Incompleteness of the Trial Around the Yushchinsky Case” (1913), and others. According to the Electronic Jewish Encyclopedia, Rozanov tries to prove the validity of the accusation of ritual murder against Jews, citing the fact that the Jewish cult is based on the shedding of blood. The combination of enthusiastic hymns to biblical Judaism with the furious preaching of anti-Semitism brought accusations of duplicity and unscrupulousness upon Rozanov. For his articles on the Beilis affair, Rozanov was expelled from the Religious-Philosophical Society (1913).

Only towards the end of his life did Rozanov begin to speak about the Jews without open hostility, sometimes even enthusiastically. In his last book (The Apocalypse of Our Time), Rozanov, expressing his attitude towards the Jews, wrote:

The idea of ”Domostroy”, Domo-stroy, is already great, sacred. Undoubtedly, the greatest “Domostroy” was given by Moses in “Exodus”, in “Deuteronomy”, etc. and continued in the Talmud, and then actually expressed and translated into life in the kahal.

The “Book of Judges of Israel”, with Ruth, with Job, free, unconstrained, always seemed to me the highest type of human existence. It is immeasurably higher and happier than kingdoms.

And so I think – the Jews are right in everything. They are right against Europe, civilization and civilizations. European civilization has spread too far out to the periphery, has become filled with voids within, has become truly “empty” and is perishing from this.

Live, Jews. I bless you in everything, as was the time of apostasy (the unfortunate time of Beilis), when I cursed you in everything. In fact, of course, you have the “tzimmes” of world history: that is, there is such a “grain” of the world, which – “we alone have preserved”. Live by them. And I believe that “all nations will be blessed by them”. – I do not believe at all in the hostility of Jews to all nations. In the darkness, in the night, we do not know – I often observed the amazing, zealous love of Jews for the Russian people and the Russian land.

May the Jew be blessed.

May the Russian be blessed too.

Hobbies

Rozanov was a passionate numismatist. His collection, kept in the State Museum of Fine Arts named after A.S. Pushkin (Numismatics Department), contains 1497 coins.

Bibliography

Legenda o velikom inkvizitore F.M. Dostoyevskogo (1894; Dostoevsky and the Legend of the Grand Inquisitor)

Literaturnye ocherki (1899; “Literary Essays”)

Sumerki prosvescheniya (1899; “Twilight of Education”)

Semeyny vopros v Rossii (1903; “The Family Question in Russia”)

Metafizika Khristianstva (1911; “Metaphysics of Christianity”):

Temnyi Lik (Dark representation of a face)

Liudi Lunnogo Sveta (People of the Moon light)

Uyedinyonnoye (1912; “Solitary Thoughts” eng. trans. Solitaria)

Opavshiye listya (1913–15; Fallen Leaves)

Apokalipsis nashego vremeni (1917–18; “The Apocalypse of our Time”)