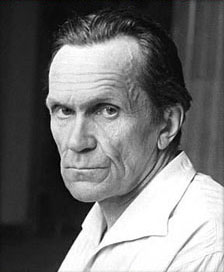

Varlam Tikhonovich Shalamov (born June 5 (18), 1907, Vologda, Vologda Governorate, Russian Empire – January 17, 1982, Moscow, USSR) was a Russian Soviet writer and poet, best known as the author of the series of short stories and essays “Kolyma Tales”, which tells about the lives of prisoners in Soviet forced labor camps in the 1930s-1950s. In his youth, Shalamov was close to the “left opposition”, which is why he was arrested in 1929 and served three years in the Vishera camp. After returning to Moscow, Shalamov began writing poetry and short stories. In 1937, he was arrested for the second time, sentenced to five years in the camps for “anti-Soviet propaganda” (Article 58-10 of the Criminal Code of the RSFSR) and transported to Kolyma in Sevvostlag. In the camp, Shalamov was sentenced to a new term, and in total he spent sixteen years in Kolyma: fourteen in general labor and as a prisoner paramedic and another two after his release. From the mid-1950s, Varlam Shalamov lived in Moscow and worked on “Kolyma Tales”.

Having failed to publish his first collection of stories during the “thaw”, the writer continued to work “for the drawer” and by 1973 he had created six collections: “Kolyma Tales”, “Left Bank”, “Artist of the Shovel”, “Essays on the Criminal World”, “Resurrection of the Larch” and “The Glove, or KR-2”.

Shalamov’s stories circulated in samizdat, and in 1966, their unauthorized publication abroad began; in the Soviet Union, Shalamov only managed to officially publish poetry collections, and “Kolyma Tales” was published after the author’s death, in the late 1980s. In the second half of the 1960s, Shalamov distanced himself from the dissident movement, a break with which was formalized in 1972, after the publication in “Literaturnaya Gazeta” of an open letter from the writer condemning pirated foreign editions of “Kolyma Tales”. Shalamov, whose health had deteriorated catastrophically, spent his last years in a Moscow nursing home for the elderly and disabled of the Literary Fund.

True recognition came to Varlam Shalamov posthumously, after English-language publications in the early 1980s and the advent of glasnost in the Soviet Union. “Kolyma Tales” is considered both as an outstanding work of art, the result of a search for a new form for depicting the catastrophe of humanism and human behavior against its backdrop, and as a historical document about the Kolyma camps.

Origin, Childhood, Youth

Varlam Shalamov was born on June 5 (18), 1907 in Vologda to the family of priest Tikhon Nikolaevich Shalamov and was named in honor of the Novgorod saint Varlaam Khutynsky, on whose movable memorial day (the first Friday of the Apostles’ Fast) his date of birth fell. Vologda had a rich history of political exile; for several generations, the city was home to populists, and then revolutionary social democrats and socialist revolutionaries; Shalamov wrote a lot about how the echoes of these events nourished and shaped him. The writer’s father was a hereditary priest, his grandfather, great-grandfather and other relatives served in the churches of Veliky Ustyug. In 1893-1904, Tikhon Shalamov served in the Orthodox mission on Kodiak Island (Aleutian and Alaskan Diocese). Varlam Shalamov’s mother, Nadezhda Aleksandrovna (née Vorobyova), came from a family of teachers and graduated from a girls’ gymnasium and pedagogical courses, but after getting married, she became a housewife. Varlam was the youngest of five surviving children. The eldest son, Valery, publicly renounced his priest father after the establishment of Soviet power, another son, Sergei, joined the Red Army and died in the Civil War in 1920. One of the sisters, Galina, left for Sukhumi after getting married, the second, Natalia, lived with her husband in Vologda.

Since 1906, Tikhon Shalamov served in the St. Sophia Cathedral, and the entire Shalamov family lived in one of the apartments in the two-story building of the cathedral clergy. Tikhon Shalamov had views that were quite liberal for his time (in the words of his son, “the Jeffersonian spirit”) and was an active public figure during the revolution of 1905-1907, he condemned anti-Semitism and gave a passionate and sympathetic sermon at the funeral service for the State Duma deputy Mikhail Gertsenshtein, who was killed by a Black Hundred member. However, his behavior in the family became more authoritarian, and Varlam Shalamov’s attitude towards him was not easy; he remembered his mother with much greater warmth. Shalamov already felt like an atheist from childhood and retained this conviction throughout his life. Nadezhda Aleksandrovna taught Varlam to read at the age of three, and in 1914 he entered the Vologda Boys’ Gymnasium named after Alexander I the Blessed. In 1918, with the start of the Civil War and foreign intervention in northern Russia, hard times began for the family: all payments due to Tikhon Shalamov ceased, the Shalamovs’ apartment was robbed and later densified, Varlam even had to sell pies baked by his mother in the market square. In the early 1920s, Tikhon Shalamov went blind, although he continued to preach until the churches were closed in 1930, and Varlam served as his guide. The gymnasium closed after the revolution, and Varlam finished his education at the Unified Labor School No. 6, Level II, which he graduated from in 1923. The school council petitioned the provincial education department to send Shalamov among the best graduates to enroll in a university, but, according to the writer’s recollections, the head of the provincial education department showed Shalamov and his blind father the finger and said: “It is precisely because you have good abilities that you will not study at a higher educational institution – at a Soviet university.”

Tikhon Shalamov – the writer’s father

As the son of a priest (“disenfranchised”), Shalamov could not study at the university; in the fall of 1924, he left for Moscow to enroll in a factory. He was hired at a tannery in Kuntsevo (then Moscow Region), first as a laborer, later as a tanner and decorator, and lived with his maternal aunt, who had a room at the Setunskaya hospital. For a short time, Shalamov worked as a teacher in the literacy program at a local school.

In 1926, he was sent by the factory to the first year of the Moscow Textile Institute and at the same time, through open enrollment, to the Soviet Law Department of the 1st Moscow University. The writer’s biographer V. Esipov calls this decision mysterious: Shalamov was attracted to literature and medicine, but he does not mention anywhere what prompted him to enroll in the Law Department. Historian S. Agishev suggests that the young man could have wanted to personally participate in the formation of the new Soviet law out of a sense of justice. Shalamov chose Moscow University and, after enrolling in the department, settled in a student dormitory on Bolshoy Cherkassky Lane. One of his roommates was a student of the Ethnology Department, the poet Musa Jalil.

At the university, Shalamov became close to a group of students from different departments who formed a discussion group in which they critically discussed the concentration of all power in Stalin’s hands and his departure from Lenin’s ideals. Many of Shalamov’s friends from those years, including his closest ones – Sarra Gezentzvei, Alexander Afanasyev, Nina Arefieva – would die during the Great Terror. The rector of Moscow University and professor of the criminal procedure department at that time was the future architect of the show trials of the Great Terror, Andrei Vyshinsky, and Shalamov happened to observe how students beat Vyshinsky for booing Christian Rakovsky’s speech at an open party meeting.

On November 7, 1927, second-year student Shalamov took part in a demonstration of the “left opposition” dedicated to the tenth anniversary of the October Revolution and held shortly after Trotsky’s expulsion from the Central Committee of the party – in fact, this was a demonstration by Trotsky’s supporters against Stalin’s policies. One of the slogans of the demonstrators was “Let’s fulfill Lenin’s last will and testament”, which was understood to be a letter from Lenin with a negative characterization of Stalin and a proposal to replace him as General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Party with someone else (“Lenin’s last will and testament”). The demonstration was dispersed with the participation of OGPU units and the university students themselves. In February 1928, Shalamov was expelled from the university “for concealing his social origin”: when filling out the questionnaire, in order to hide his status as a “disenfranchised person”, he indicated his father as a “disabled employee” and not as a “clergyman”, which was revealed in a denunciation by his classmate and fellow countryman. In Moscow, Shalamov immersed himself in the life of literary societies and circles. He recalled the funeral of Sergei Yesenin on December 31, 1925, and the crowd of thousands of people who saw him off, including eighteen-year-old Shalamov, as an important event. In 1927, he responded to the call of the magazine Novy LEF for readers to send “new, unusual rhymes”, and attached his own poems to the rhymes. Nikolai Aseyev, one of the idols of the youth of those years, responded to him with a short letter with a review. Shalamov attended Mayakovsky’s public readings; he would describe his impressions of his performances in 1926-1927 in an essay for Ogonyok in 1934. Shalamov tried to attend the LEF circles of Osip Brik and Sergei Tretyakov, but left rather caustic memories of both, although he later acknowledged the enormous influence of Brik’s theoretical works on his own prose.

First arrest. Vishersky Camp

On February 19, 1929, Shalamov was arrested during a raid on an underground printing house at 26 Sretenka Street, where the materials of the “left opposition” were printed, including “Lenin’s last will.” Accused under Part 10 of Article 58 of the Criminal Code of the RSFSR (“anti-Soviet agitation”), Shalamov was held in Butyrka Prison. During the investigation, he refused to testify, stating only that “the leadership of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) is sliding to the right, contributing to the strengthening of capitalist elements in the city and village, and thereby serving the cause of the restoration of capitalism in the USSR” and that he himself shared “the views of the opposition.” In his autobiographical essay “Butyrka Prison” and in the story “The Best Praise,” Shalamov later wrote that he was truly happy in prison because he believed that he was continuing the great revolutionary tradition of the Socialist Revolutionaries and Narodnaya Volya members, for whom he had great respect until the end of his life. On March 22, 1929, by a resolution of the Special Conference of the OGPU, on a reclassified charge (the charge of anti-Soviet propaganda was dropped), Shalamov was sentenced to three years in a concentration camp as a socially dangerous element (Article 35 of the Criminal Code of the RSFSR of 1926).

Shalamov served his three-year sentence in the Vishera camp (Vishlag) in the Northern Urals, where he arrived on April 19, 1929, after traveling by rail to Solikamsk and walking for almost 100 kilometers. As a prisoner with an education, in the fall of 1929 he was appointed a foreman at the construction of the Berezniki Chemical Plant in the village of Lenva, and was soon promoted to the position of head of the accounting and distribution department of the Berezniki branch of Vishlag, where he was responsible for distributing the prisoners’ labor – a very high position for a prisoner. In Vishlag, Shalamov encountered the work of Eduard Berzin, who from 1930 supervised the construction of the Vishersky Pulp and Paper Mill, one of the construction projects of the First Five-Year Plan. The writer personally met Berzin at meetings, once accompanied him on a flight over the controlled territories in a seaplane and then remembered him as a gifted organizer, who effectively organized the work and sincerely cared about the prisoners, who were shod, clothed and fed. Later, he described his own enthusiastic mood: “When Berzin arrived, and most importantly, Berzin’s people arrived, everything seemed rosy to me, and I was ready to move mountains and take on any responsibility.” In his later stories (“At the Stirrup,” “Khan-Girey”), Shalamov described Berzin critically, using his figure as an illustration of the depravity of the entire system of relations arising between the boss and the prisoners, which awakens the worst qualities in everyone. In October 1931, Shalamov was released early in accordance with an order according to which prisoners who held administrative positions and had no penalties ceased serving their sentences, were reinstated in their rights and were given the opportunity to work in the same positions as civilians, for a fairly attractive salary. However, Shalamov refused to stay in Vishera and in the following months visited Moscow and Vologda. Then he returned to Berezniki, where he worked for several months as the head of the labor economics bureau at the thermal power plant of the Berezniki chemical plant. V. Esipov suggests that this was done in order to create a clean work record before returning to Moscow. As a result of these events and bureaucratic inconsistency, the resolution of the Special Conference of the OGPU of February 14, 1932, was not implemented. According to it, after his release (by the time the resolution was issued, the three-year term had not yet expired), Shalamov was to be exiled to the Northern Territory for three years: when the documents arrived at Vishlag, Shalamov was no longer there. Shalamov described his first arrest, imprisonment in Butyrka prison, and serving his term in the Vishera camp in a series of autobiographical stories and essays from the early 1970s, which are united in what the author calls an “anti-novel” called “Vishera”. The writer summed up his first camp experience: “What did Vishera give me? These were three years of disappointment in friends, unfulfilled childhood hopes. An extraordinary confidence in my own vitality. Having been tested by a difficult test – starting with the stage from Solikamsk to the North in April 1929 – alone, without friends and like-minded people, I passed the test – physical and moral. I stood firmly on my feet and was not afraid of life. I understood well that life is a serious thing, but there is no need to be afraid of it. I was ready to live. ” In the Vishera camp, Shalamov met his future wife Galina Ignatyevna Gudz, who came there from Moscow to meet her young husband, and Shalamov “beat her off” by agreeing to meet immediately after liberation.

Life in Moscow. The beginning of literary activity

In February 1932, Shalamov returned to Moscow and soon got a job at the trade union magazine “For shock work”. In March 1934, he transferred to another trade union magazine “For mastering technology”, and in 1935 – to the magazine of the Union People’s Commissariat of Heavy Industry “For industrial personnel”. For these and other magazines, Shalamov published production articles, essays, and feuilletons, usually under pseudonyms. On July 29, 1934, Shalamov married Galina Gudz, which allowed him to move from his sister’s apartment to the five-room apartment of his wife’s parents (the “old Bolshevik” Ignatius Gudz was a high-ranking employee of the People’s Commissariat of Education of the RSFSR) in Chisty Lane. In April 1935, Varlam and Galina had a daughter, Elena.

During this same period, Shalamov began writing poetry and fiction—short stories. His two notable publications from that time were the short stories “The Three Deaths of Doctor Austino,” obviously inspired by the rise of fascist regimes in Europe and already containing Shalamov’s characteristic image of a hero faced with a moral dilemma (published in 1936 in the magazine “October”), and “The Peacock and the Tree” (1937, “Literary Contemporary”; by the time the issue was published, the writer had already been arrested). During this period, Shalamov experienced a fascination with Babel’s prose, but later became disillusioned with it, both because of Babel’s romanticization of the life of a thief and stylistically. In a later essay, he described how he learned to compose a short story: “I once took a pencil and crossed out all the beauties of Babel’s stories, all these ‘fires that resembled resurrections,’ and looked at what would remain. Little was left of Babel, and nothing at all was left of Larisa Reisner.” According to his own statement, Shalamov wrote up to 150 stories during this period, but after his arrest, Galina burned them along with her husband’s other papers.

In March 1933 and December 1934, Varlam’s father and mother died in Vologda, respectively; both times he left Moscow for the funerals. During his first visit, his mother told Shalamov how, in extreme poverty, the blind Tikhon Nikolaevich chopped up the gold cross he had received for his service on Kodiak in order to get some money for it at the Torgsin store. Shalamov later described this story in his short story “The Cross.”

Second Arrest. Kolyma

In 1936, Shalamov, at the insistence of his brother-in-law, the prominent Chekist Boris Gudz, and his wife, wrote a renunciation of his Trotskyist past to the Lubyanka. In the story “Asya”, Shalamov described how he and Galina discussed this statement with Galina and Boris’s sister Alexandra (Asya), who believed that her family was “turning in” Varlam to save the others from harm. Alexandra Gudz was arrested in December 1936, later convicted of “counterrevolutionary activity” and died in a camp in 1944.

In December 1936, Shalamov was interrogated at the Frunzensky District Department of the NKVD, and arrested on January 12, 1937. The writer believed that this happened on the basis of a denunciation by his brother-in-law, but this is not confirmed by the materials of the investigation. Shalamov was accused of conducting “counterrevolutionary Trotskyist activity” – maintaining ties with other former Trotskyists after returning from exile (Article 58-10 of the Criminal Code of the RSFSR, “anti-Soviet agitation”). During interrogations — torture was not yet the norm in the first half of 1937, and Shalamov was not subjected to it — he admitted contacts with only six people, five of whom (close friends from the time of the circle in the late 1920s), according to V. Esipov, should not have been harmed by this, because they were in exile at the time, and not in Moscow, and the identity of the sixth person has not been established. During the investigation, Shalamov was again held in Butyrka prison; as a seasoned prisoner, he was elected cell leader. There he met the Socialist Revolutionary, member of the Society of Former Political Prisoners and Exiled Settlers Alexander Andreyev, whom he later considered a moral authority and one of the most important people in his life. Shalamov considered his farewell words, “You can sit in prison,” to be “the best, most significant, most responsible praise.” Andreev is portrayed under his own name in several stories, including “The Best Praise”, and the same name is borne by the recurring character in many stories – the writer’s alter ego. On June 2, 1937, Shalamov’s case was considered by the Special Conference of the NKVD of the USSR, he was sentenced to five years in the camps. The writer’s relatives were also subjected to repression: his wife Galina was exiled to the Kaganovichsky district of the Chardzhou region until 1946, B. I. Gudz was fired during the purge within the NKVD, and also expelled from the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks), which, however, was a rather easy fate (many of his colleagues were shot). The mutual hatred of Shalamov and Gudz remained forever, and when the writer illegally visited his family in Moscow in the early 1950s, Gudz, who lived nearby, called the police several times to arrest him for violating the residence rules.

The convoy from Moscow departed by rail at the end of June 1937 and arrived in Vladivostok a little over a month later. On August 14, Shalamov was delivered to Nagaev Bay (Magadan) on the steamship Kulu with a large consignment of prisoners, from where they were then taken by car to the Partizan gold mine. Shalamov recalled that on the steamship he met the convict Iulian Khrenov, the hero of Mayakovsky’s poem “Khrenov’s Story about Kuznetskstroy and the People of Kuznetsk”. The writer spent the next fourteen years in the Sevvostlag camps in Kolyma.

At the mine, Shalamov worked as an ordinary miner, armed with a pick. He later recalled: “I am tall, and this was a source of all kinds of torment for me during my entire imprisonment. I did not have enough rations, I weakened earlier than everyone else.” He did not refuse to work – this would have meant execution, but he never sought to fulfill production standards and increased rations, firstly, following the unwritten law “It is not a small ration that ruins, but a large one” (working more in the expectation of increased nutrition, a prisoner actually loses strength faster), and secondly, because he felt disgust for slave labor. In December 1938, he was removed from work and taken to the NKVD department, where the senior operative sent him to “Serpentinka”, a pre-trial prison and place of mass executions. For an unknown reason, he was not accepted there; in the story “The Conspiracy of Lawyers” Shalamov describes these events, linking the immediate collapse of the newly opened case on the “conspiracy” with the purges in the NKVD that followed the removal of Yezhov from the post of People’s Commissar of Internal Affairs in the same month. Shalamov spent the winter of 1938-1939 in Magadan, in quarantine, declared due to a typhoid fever epidemic among prisoners. In April 1939, he was sent to a geological exploration party at a coal mine near the Black Lake pass (near the village of Atka).

Shalamov recalled the summer of 1939 as the time when he began to “resurrect”: digging exploratory pits was considered, by Kolyma standards, gentle work, and the geologists had good food. In August 1940, exploration at Black Lake was closed as unpromising, and Shalamov was transferred to the Kadykchan site. Life there is described in the story “Engineer Kiselyov”: the head of the section (in the story he is shown under his real name) turned out to be a sadist who beat the prisoners and as punishment placed them in an “ice cell” cut out of the rock for the night, and Shalamov mentioned to his cellmates that he intended to slap him the next time the authorities visited, which Kiselyov immediately learned about. Thanks to the help of a camp paramedic he knew, Shalamov was able to transfer to the neighboring section of Arkagala, where he spent almost the entire 1941 and 1942, working in difficult conditions in coal mining.

In January 1942, Shalamov’s five-year term expired, but in accordance with Directive No. 221 of the People’s Commissar of Internal Affairs and the Prosecutor of the USSR dated June 22, 1941, “the release of counterrevolutionaries, bandits, recidivists and other dangerous criminals from camps, prisons and colonies” was stopped until the end of the war; on June 23, the corresponding order for the Sevvostlag camps was issued by the head of Dalstroi Nikishov. In December 1942, Shalamov ended up in a “penal” zone – the Dzhelgala gold mine near the modern settlement of Yagodnoye. In the story “My Trial” he is given the following description: “The Dzhelgala camp is located on a high mountain – the mine faces are below, in the gorge. This means that after many hours of grueling work, people will crawl along icy steps cut out of the snow, clutching at scraps of frostbitten willow, crawling upwards, exhausted by their last strength, dragging firewood on their backs – a daily portion of firewood for heating the barracks.” On June 3, 1943, Shalamov was arrested in a new criminal case. These events are described by him in the story “My Trial”, where the main prosecution witnesses are listed under their real names – prisoners of the same camp who testified against Shalamov: foreman Nesterenko, assistant foreman, former employee of the People’s Commissariat of Defense Industry E. B. Krivitsky and former capital journalist I. P. Zaslavsky; the latter two were known in the camp as “regular” witnesses in new criminal cases opened there.

According to the indictment, Shalamov “expressed dissatisfaction with the policies of the Communist Party, while at the same time praising Trotsky’s counterrevolutionary platform <…> made slanderous fabrications about the policies of the Soviet government in the area of developing Russian culture <…> made counterrevolutionary fabrications about the leaders of the Soviet government, slandered the Stakhanovite movement and shock workers, praised German military equipment and the command staff of the Hitlerite army, and spread slanderous fabrications about the Red Army.” The writer insisted that one of the points of the indictment was his statement that Ivan Bunin (an émigré and critic of the Soviet government) was a great Russian writer, but this detail is not included in the materials of the investigation. The tribunal session took place on June 22, 1943, in Yagodnoye, where Shalamov was taken by foot escort. He was found guilty of anti-Soviet agitation (Article 58-10, Part II of the Criminal Code of the RSFSR) and received ten years of imprisonment in a camp with a 5-year ban on his rights.

Shalamov spent the autumn and winter of 1943 on a so-called “berry mission”: a group of prisoners with a light escort, but also with a reduced food ration, collected dwarf pine needles and berries for anti-scorbutic measures in the camp. Around January 1944, in a state of extreme exhaustion (alimentary dystrophy and polyavitaminosis), Shalamov was taken to the camp hospital in the village of Belichya, where he spent almost a year with breaks. After being discharged and returning to work in the taiga in March 1944, thanks to the intercession of the hospital’s head doctor Nina Savoyeva, he was first employed as an orderly, and later as a cultural organizer (responsible for educational work). Nina Savoyeva and paramedic Boris Lesnyak left their memoirs about working in Belichya and meeting Shalamov; Lesnyak’s memoirs were written after Shalamov had broken off contact with him, and are largely biased. During the same period, in February 1944, the writer received a note from Alexandra (Asia) Gudz, who was in one of the neighboring camps, but did not have time to meet her because she died of lobar pneumonia. In the spring of 1945, an NKVD officer who knew Shalamov noticed him in the hospital and returned him to work; this time he was sent to the Spokoiny mine. He was there when news arrived that the war was over. A few months later, Shalamov was hospitalized again, but was discharged after Savoeva was transferred to another hospital in the fall of 1945. He spent the following months in the taiga logging at Almazny Spring and again in the penal zone at Dzhezgal, where he was moved after an escape attempt. In the spring of 1946, Shalamov, finding himself in a transit barracks in Susuman, was able to pass a note to a friend, paramedic Andrei Pantyukhov, who made every effort to pull the sick Shalamov out of work and get him into the medical unit. A little later, again under Pantyukhov’s protection, Shalamov was sent to the newly opened eight-month paramedic courses at the 23rd kilometer of the Kolyma Highway. The lecturers at these courses included repressed major scientists, such as Ya. S. Meerzon. Living conditions at the courses were incomparable to those of prisoners in general work, but Shalamov actively used his chance and acquired practical medical skills. After his release, Shalamov corresponded with Pantyukhov, claiming that he owed him his life. He served the rest of his term in Kolyma as a paramedic and never again found himself in general work.

In December 1946, after completing his courses, the writer was sent to the main hospital of USVITLag in the village of Debin, 500 kilometers from Magadan, on the left bank of the Kolyma. The hospital was located in a pre-war three-story, well-heated brick building, where Shalamov both worked and lived (at night, he slept in the linen room in the department). After being transferred to the hospital, literature returned to Shalamov’s life: in the evenings, he read poetry by his favorite poets with two other prisoners, screenwriter Arkady Dobrovolsky and actor and poet Valentin Portugalov. In the same hospital, he met X-ray technician Georgy Demidov, who later also wrote camp prose. Shalamov called Demidov, who was portrayed as the title character of the story “The Life of Engineer Kipreev,” “the most worthy of the people I met in Kolyma.” In 1949-1950, Shalamov worked as a paramedic on a “forest mission” at the Duskanya spring: he received visitors at the paramedic station in a hut and toured the areas by sled in the winter and by motorboat in the summer. Here he had a lot of free time, which he could devote to writing poetry. During these months, he composed and wrote down dozens of poems by hand in notebooks he had stitched himself and, as he believed, developed as a poet.

Return to Moscow

The ten years assigned by the 1943 sentence were to expire in 1953, but Shalamov was released early on October 20, 1951, according to the rules of Article 127 of the Correctional Labor Code of the RSFSR on the inclusion of working days in the term of imprisonment. He was planning to return to the “mainland” the following spring, after navigation opened, but due to bureaucratic red tape he lost the right to paid travel home and was forced to stay to earn money for the trip. On August 20, 1952, Shalamov, on the orders of the sanitary department of “Dalstroy”, went to work as a paramedic at the camp point of the Kyubyuminsky road maintenance section, located in the village of Tomtor in Yakutia (not far from Oymyakon).

Shalamov decided to send his poems to the living poet he valued most, Boris Pasternak, and in February 1952 he gave two notebooks along with a letter to his wife, free doctor Elena Mamuchashvili, who was flying away on vacation. In the summer, Pasternak received them from Galina Gudz and sent a response through her with a detailed critical analysis of the poems: “I bow before the seriousness and severity of your fate and the freshness of your inclinations (keen observation, the gift of musicality, susceptibility to the tangible, material side of the word), evidence of which is scattered in abundance in your books. And I simply do not know how to talk about your shortcomings, because these are not the flaws of your personal nature, but the examples that you followed and considered creatively authoritative are to blame for them, the influences are to blame, and first of all – mine. <…> You feel and understand too much by nature and have experienced too sensitive blows to be able to close yourself off in only judgments about your data, about your talent. On the other hand, our time is too old and unkind to be able to apply only these lightened standards to what has been done. Until you completely part with false, incomplete rhyme, sloppiness of rhymes, leading to sloppiness of language and instability, uncertainty of the whole, I, in the strict sense, refuse to recognize your notes as poetry, and until you learn to distinguish what is written from nature (either external or internal) from what is contrived, I cannot recognize your poetic world, your artistic nature, as poetry.” Shalamov received an answer only in December, having covered 500 kilometers between Kyubyuma and Debin by sleigh and hitchhiking.

On September 30, 1953, Shalamov received his pay at Dalstroi. With the money he had saved, he joined the stream of prisoners leaving Kolyma as a result of Beria’s amnesty. In early November, Shalamov flew from Oymyakon to Yakutsk, from where he traveled to Irkutsk, where he boarded an overcrowded train. On November 12, he arrived in Moscow, where his wife met him. At the same time, probably at the insistence of Boris Gudz, Shalamov was not allowed into the apartment where he and his family had lived before his arrest. The next day, he met with Pasternak. After that, Shalamov, as a former prisoner who was forbidden to live or simply be in Moscow for more than a day, left for Konakovo (Kalinin Oblast). He was unable to find a job as a paramedic (the Dalstroy paramedic courses were not recognized as proper medical education) and in the following months he worked first as a commodity expert in Ozerki, then, from July 1954, as a supply agent at the Reshetnikovsky peat enterprise in the village of Turkmen. He lived in Turkmen for the next two years. He continued to write poetry, and a significant portion of the poems of the 1950s, collections of which are known collectively as the Kolyma Notebooks, were written not in Kolyma, but in Ozerki and Turkmen. During this same period, Shalamov began working on the Kolyma Tales. The Snake Charmer, Apostle Paul, At Night, Carpenters, and Cherry Brandy are dated 1954. In a letter to Arkady Dobrovolsky on March 12, 1955, Shalamov wrote: “I will now have 700-800 poems and about ten stories, of which a hundred are needed according to the planned architecture.” The divorce from Galina Gudz also dates back to this period. Galina and her and Varlam’s daughter Elena lived in Moscow, Galina helped Varlam in his correspondence with Pasternak, but their communication was difficult due to the discrepancy in their life positions. Elena (after an early marriage, she changed her surname to Yanushevskaya) practically did not know her father, was a convinced Komsomol member and refused to communicate with him. After 1956, Shalamov stopped communicating with them.

In May 1955, the writer sent an application for rehabilitation to the Prosecutor General of the USSR. A year later, the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the USSR reviewed it and on July 18, 1956, overturned the resolution of the Special Conference of the NKVD of the USSR of 1937 and the verdict of the military tribunal of 1943.

In 1956, Shalamov had a short affair with Pasternak’s long-time lover Olga Ivinskaya, whom he had known since the 1930s. The break with her led to the end of contacts with Pasternak. In October 1956, Shalamov married Olga Neklyudova, whom he had met in Pasternak and Ivinskaya’s circle of friends. He moved into Olga’s communal apartment on Gogolevsky Boulevard, where she lived with her son Sergei from a previous marriage. The following year, Olga received an apartment in a post-war building on Khoroshevskoye Highway, and the family moved there.

Kolyma Tales. Controversy with Solzhenitsyn

At the end of 1956, Shalamov got a job as a freelance correspondent for the magazine Moskva. A small selection of poems from the Kolyma Notebooks was published in Znamya (No. 5, 1957). Five poems were published in Moskva (No. 3, 1958). In September 1957, Shalamov lost consciousness and was hospitalized. He stayed in the Botkin Hospital until April 1958 and received a disability for Meniere’s disease – a vestibular disorder acquired in childhood, aggravated by the camps.

Subsequently, Shalamov’s attending physician in his last years suggested that this could have been the first attack of Huntington’s disease. From that time on, the writer was constantly accompanied by dizziness, falls due to loss of coordination and insomnia, because of which he took Nembutal for many years (he often looked for a prescription drug through his doctor friends), and towards the end of his life he began to go deaf. In 1963, the third group of disability was changed to the second. Due to health reasons, Shalamov was unable to continue working at Moskva, and in 1959-1964, his main source of income was working as a freelance reviewer of manuscripts sent to the editors at Novy Mir. At the same time, he worked non-stop on Kolyma Tales. In 1961, his first collection of poems, Ognivo, was published, and in 1964, his second, Rustle of Leaves, both received positive reviews in literary magazines. In anticipation of a production at the M. N. Yermolova Theater, where director Leonid Varpakhovsky, who had returned from Kolyma, worked, Shalamov wrote a “camp” play, “Anna Ivanovna,” but these plans were not realized. In the early 1960s, at the suggestion of the magazine “Znamya,” Shalamov prepared an essay-memoir, “The Twenties,” in which he focused primarily on literary life. The essay was not published, and Shalamov continued working on a pre-Kolyma cycle of memoirs (“Moscow in the 20s – 30s”). Since 1965, the writer received an increased pension for performing hard and hazardous work (thanks to the testimony of friends – former camp inmates, he confirmed his work experience at the Kolyma gold mines).

By 1962, Shalamov had prepared about sixty stories, and during this period he submitted eighteen of them to Novy Mir, which formed the backbone of the first collection, entitled Kolyma Tales. It is not known exactly how and when the manuscript was rejected, but there is no reliable documentary evidence that the question of its publication in Novy Mir was actually considered, nor that the magazine’s editor-in-chief, Alexander Tvardovsky, was ever acquainted with the stories. Shalamov also sent Kolyma Tales to the Sovetsky Pisatel publishing house, from where he received a negative response in November of the following year, 1963.

Tvardovsky waged an administrative struggle throughout 1962 for the publication of Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s story One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, which became one of the first depictions of Stalin’s camps in the Soviet press, and in November 1962 One Day was published in Novy Mir. After the publication of One Day, Shalamov entered into correspondence with its author, beginning with a detailed and generally complimentary review of the story. Noting the numerous literary merits of the story, the apt description of the protagonist and some other characters, Shalamov simultaneously stated that Solzhenitsyn had described an “easy” camp, by no means a Kolyma camp. In September 1963, Shalamov, at Solzhenitsyn’s invitation, came to Solotcha near Ryazan, where the author of One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich was living at the time. The trip left an unpleasant impression on him, and he returned after two days, not a week as planned. The following year, they met again, when Solzhenitsyn invited Shalamov to participate in the work on The Gulag Archipelago. Shalamov refused unequivocally: by that time he already considered Solzhenitsyn not a very talented but tight-fisted “businessman” who sought success at any cost, primarily in the West, while the author of “Kolyma Tales” was more interested in reaching his native reader. Later, through A. Khrabrovitsky, Shalamov conveyed to Solzhenitsyn a ban on any use of his name and his materials. The only Kolyma story legally published in the USSR during Shalamov’s lifetime was the miniature sketch “Dwarf Tree”, published in the magazine “Rural Youth” (No. 3, 1965), where the writer’s friend Fedot Suchkov worked. Only the last sentence could hint at the author’s camp experience: “And the firewood from the dwarf tree is hotter.” At the same time, the first collection of “Kolyma Tales”, which the writer introduced to his close friends, began to circulate in samizdat, and in 1965 Shalamov completed his second collection, “Left Bank”. On May 13, 1965, at a semi-official evening in memory of Osip Mandelstam, Shalamov read the story “Cherry Brandy”, an artistic fantasy about the poet’s last hours in a transit camp. According to the transcript of the evening, “a note was passed along the rows to the presidium, having, of course, managed to read it on the way; someone from the management asked to “tactfully stop this speech”. The chairman (it was Ilya Ehrenburg) put the note in his pocket, Shalamov continued reading.” Shalamov’s speech was received enthusiastically, and he entered the literary circle of Ehrenburg, Nadezhda Mandelstam, Alexander Galich, Lev Kopelev and Natalia Kind. In 1965, he was introduced to Anna Akhmatova, who was already seriously ill. Shalamov developed a particularly trusting relationship with Nadezhda Mandelstam. He became one of the first readers of the first volume of “Memoirs”, in a review of which he wrote: “A new great man is entering the history of the Russian intelligentsia, Russian literature, Russian public life. <…> It is not Mandelstam’s friend who is entering the history of our society, but a strict judge of the time, a woman who has accomplished and is accomplishing a moral feat of extraordinary difficulty.” Mandelstam assessed “Kolyma Tales” as “the best prose in Russia for many, many years <…> And perhaps even the best prose of the twentieth century.” Meeting Ehrenburg’s secretary Natalya Stolyarova turned out to be especially valuable for the writer, since Stolyarova was the daughter of the Socialist Revolutionary Natalya Klimova, a participant in the assassination attempt on Stolypin and the author of the journalistic “Letter before Execution”, whose fate and personality had attracted Shalamov before. Shalamov came up with the idea for a story about Klimova, and Stolyarova provided him with documents from her personal archive, including correspondence between Klimova and her Socialist Revolutionary husband Ivan Stolyarov, but in the end the story did not come out – Shalamov only wrote the story “The Gold Medal”.

Immediately after the trial of Yuri Daniel and Andrei Sinyavsky, which ended in early 1966. They were convicted of publishing works in the West and under pseudonyms that “defame the Soviet state and social system,” Shalamov, probably at the request of acquaintances from the dissident community, prepared “A Letter to an Old Friend” — a lengthy account by an anonymous witness (Shalamov was not present at the trial, but was sufficiently privy to its details) about the trial, full of admiration for the accused. The letter expressed an important thought for Shalamov: Sinyavsky and Daniel were the first defendants in a public political trial held in the USSR since the trial of the Socialist Revolutionaries in 1922 who behaved courageously and did not repent. “A Letter to an Old Friend” was included in the “White Book,” a collection of materials about the trial prepared and published abroad by Alexander Ginzburg. In 1968, in the verdict following the “trial of four”, where Ginzburg was one of the accused, “Letter to an old friend” was formally characterized as an anti-Soviet text.

Ginzburg refused to name the author of the letter at the trial and revealed Shalamov’s authorship only in 1986, after his death, but due to leaks it became known to the KGB. The writer was put under surveillance, and he himself became disillusioned with the movement, which he considered to consist of “half fools, half informers, but there are few fools these days.” At the same time, he stopped communicating with N. Ya. Mandelstam’s circle. According to literary scholar Elena Mikhailik, Shalamov’s commitment to the ethics of the Russian revolutionary movement of the beginning of the century led to him making demands on both the authorities and dissidents that were “hopelessly outdated by the mid-1930s.”

In 1966, Shalamov met an archivist, an employee of the TsGALI acquisition archive, Irina Sirotinskaya, who, having read “Kolyma Tales” in samizdat, found the writer and offered to hand over the manuscripts to the state archive for safekeeping. Their acquaintance grew into a long-term close relationship, despite the age difference (Shalamov was twenty-five years older) and the fact that Sirotinskaya was married and had three children. That same year, Shalamov divorced Neklyudova, but continued to share an apartment with her; two years later, through the Literary Fund, he was able to obtain a separate room in a communal apartment on the floor above.

In 1968, Shalamov completed the collection “Resurrection of the Larch”, dedicating it to Sirotinskaya. Sirotinskaya’s trip to Vologda that same year prompted him to write an autobiographical work about his childhood and family, “The Fourth Vologda” (completed in 1971). During the same period, “Vishersky Anti-Roman” was written. In 1967, the third poetry collection “Road and Fate” was published in “Soviet Writer”, notable for the fact that in the same year it was reviewed in the newspaper “Russkaya Mysl” by the leading literary critic of the Russian diaspora Georgy Adamovich, who was familiar with “Kolyma Tales” and had already analyzed Shalamov’s poems based on them. In the 1960s, poems by Bulgarian poets Kirill Hristov and Nikolay Rakitin, who wrote in Yiddish and, like the translator, had been through the camps of Chaim Maltinsky, were published in Shalamov’s translations. In 1973, Shalamov finished work on the last collection of Kolyma Tales, The Glove, or KR-2.

In 1966, the American Slavic scholar Clarence Brown, who was well acquainted with Nadezhda Mandelstam and met with Shalamov himself in her apartment, apparently with the writer’s consent, took the manuscript of Kolyma Tales. Brown gave it to the editor of the New York Novy Zhurnal, a first-wave emigrant, Roman Gul, for publication. In December of that year, four stories were published in Novy Zhurnal; over the next ten years, Gul published forty-nine stories from Kolyma Tales, The Left Bank, The Artist of the Spade, and The Resurrection of the Larch, all the while accompanying them with his own editorial corrections (the text of Cherry Brandy was particularly heavily distorted). All this happened without the knowledge of the writer, for whom it was extremely important to publish the stories together and in a certain order, while preserving the author’s composition.

The following publications were also unauthorized: two stories were published in January 1967 in the émigré magazine Posev, and in the same year the German translation of most of the first collection of Kolyma Tales was published in Cologne as a separate book under the title Artikel 58 (Article 58) and with the author’s name misspelled (Schalanow). Since 1970, the stories in the author’s version, based on another manuscript, taken out by Irina Kanevskaya-Khenkina without the author’s knowledge, were published in the magazine Grani. In 1971, two stories were published in English in an anthology of uncensored Soviet literature edited by Michael Scammell. The first publication of the stories in Russian as a single book took place much later – in London in 1978, the compiler and author of the preface was Mikhail Geller. On February 23, 1972, Literaturnaya Gazeta published an open letter from Shalamov, in which the author condemned in the strongest terms the publication of Kolyma Tales abroad without his knowledge in anti-Soviet publications. The letter ended with the statement that “the problems of Kolyma Tales have long been removed by life,” which caused the greatest rejection among Shalamov’s friends and colleagues: it was read both as the writer’s renunciation of his own works and as a betrayal of Soviet dissidents, who were still receiving prison sentences. Even Irina Sirotinskaya condemned Shalamov’s actions. Opinions were expressed that the text of the letter was not written by Shalamov or that he did so under duress.

One of the compilers of the Chronicle of Current Events, Pyotr Yakir, wrote an open letter to Shalamov, which was annotated in the 24th issue of the bulletin: “Highly appreciating the work of his addressee and his moral qualities, the author expresses his pity for him in connection with the circumstances that forced the author of Kolyma Tales to ‘sign’ the letter <…>. Shalamov is addressed with ‘only one reproach’ – regarding his phrase that ‘the problems of Kolyma Tales have long been removed by life’.” Solzhenitsyn responded in samizdat with a remark that was also reproduced in a footnote in the second volume of The Gulag Archipelago: “The abdication was printed in a mourning frame, and that’s how we understood it all: Shalamov had died” (upon learning of this, Shalamov wrote a letter with the words: “With an important feeling and with pride, I consider myself the first victim of the Cold War to fall at your hand. <…> I really died for you and your friends, but not when Literaturnaya Gazeta published my letter, but much earlier – in September 1966,” but ultimately did not send it).

There is now virtually no doubt that the letter was written by Shalamov personally and reflects his own position. He wrote in his diary: “It’s ridiculous to think that you can get some kind of signature from me. At gunpoint. My statement, its language, its style are my own. <…> If we were talking about the Times newspaper, I would have found a special language, but for Posev there is no other language than abuse. My letter is written like that, and Posev does not deserve any other. I have already given an artistic answer to this problem in the story “Unconverted”, written in 1957, and they did not feel anything, this forced me to give a different interpretation of these problems.

I have never given my stories abroad for a thousand reasons. First, it is a different story. Second, complete indifference to fate. Third, the hopelessness of translation and, in general, everything is within the boundaries of language.” The discussion is only about who initiated the publication. According to A. Gladkov’s memoirs, the idea of the letter belonged to an official functionary, the then first secretary of the board of the Union of Writers of the USSR Georgy Markov, and Shalamov, who at that time had the printing of the next collection “Moscow Clouds” blocked, agreed to it. V. Esipov cites another diary entry by the writer that he would have “raised the alarm a year ago” if he had learned about the publications earlier, and the advice he received only influenced the final form.

It is noteworthy that Shalamov especially singles out “Sowing”. Only two stories were published in “Sowing”, but this magazine, published by the “People’s Labor Union”, had the most odious reputation. In the phrase about the problems of the “Kolyma Tales” being removed by life, literary scholar Leona Toker sees a direct quote from Bukharin’s speech at the 14th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) (1925): he responded to criticism of his statements in the intra-party discussions around the NEP with the words: “I do not renounce the quote from Krasnaya Nov’. <…> The question in the formulation in which it stood in 1921 has been removed by life.” Toker concludes that Shalamov, who was well acquainted with the rhetoric of this period, essentially also meant: “I do not renounce.”

The last years

In 1972-1973, Shalamov was accepted into the Union of Writers of the USSR, published a collection of poems called “Moscow Clouds” and, moving out of a house on Khoroshevskoye Shosse that was slated for demolition, received an apartment in house No. 2 on Vasilyevskaya Street through the Literary Fund as a pensioner and disabled person. He published poems in the magazine “Youth” a lot, almost every year. Shalamov conducted an extensive correspondence, among his correspondents were David Samoilov, Yuri Lotman, Dmitry Likhachev and Vadim Kozhinov. It is known that in 1974, Shalamov attended the second game of the final Candidates Match in chess between Anatoly Karpov and Viktor Korchnoi. In 1976, Shalamov broke up with Irina Sirotinskaya. In 1977, his last poetry collection, “Boiling Point”, was published. V. Shalamov’s grave at the Kuntsevo Cemetery

During the 1970s, the writer’s health gradually deteriorated due to progressive Huntington’s disease; due to the increasing frequency of attacks and impaired coordination, he always carried a certificate with first aid instructions in case an attack occurred on the street. In April 1979, after his apartment was robbed (while Shalamov was in the hospital for a month and a half), he gave his archive to Sirotinskaya. In May 1979, the seriously ill writer was transferred to the Literary Fund’s nursing home for the elderly and disabled on Latsis Street in Tushino, where he spent the last three years of his life.

Shalamov continued to be visited by friends and relatives – primarily Sirotinskaya, Alexander Morozov and the doctor Elena Zakharova (daughter of the translator Viktor Khinkis). According to Zakharova’s recollections, the nursing home, which housed mostly patients who were unable to care for themselves, was short of staff, and care was limited to formalities. Shalamov had almost lost his sight and hearing, and it was very difficult for him to reach the toilet, which was equipped in the “dressing room” of his ward. Nevertheless, Shalamov continued to compose: new poems, recorded in 1981 by Sirotinskaya, were published in the next issue of Yunost. A little earlier, in the fall of 1980, Morozov recorded and sent to the West a cycle of poems published in the Parisian magazine Vestnik RKhD (most of them, however, were written in the mid-1970s and were mistakenly perceived by Morozov as new). According to Sirotinskaya, after the publication in the “Bulletin of the Russian Christian Democrats”, “Shalamov’s poor, defenseless old age became the subject of a show”: journalists, including Western ones, began to show interest in the deplorable state in which the writer found himself, and one could see a photojournalist taking an effective staged photo, while a nurse, probably assigned by the KGB, was watching.

In the fall of 1981, after a superficial examination by a medical commission, Shalamov was diagnosed with senile dementia. On January 15, 1982, he was transferred to a neuropsychiatric boarding school on Abramtsevskaya Street (Lianozovo district). Esipov suggests that the transfer was motivated not so much by medical considerations as it was intended to isolate Shalamov from visitors. During the transportation, the writer caught a cold, fell ill with pneumonia and died on January 17, 1982; the cause of death was listed as heart failure.

Despite the fact that Shalamov had been an unbeliever all his life, Zakharova, who knew that he was the son of a priest, insisted on an Orthodox funeral. The funeral service in the Church of St. Nicholas in Kuznetsy was conducted by Archpriest Alexander Kulikov, the wake was organized by philosopher Sergei Khoruzhy. Shalamov was buried in the Kuntsevo Cemetery in Moscow (section 8). According to the recollections of A. Morozov, about 150 people attended the ceremony, he and Fedot Suchkov read the deceased’s poems. Later, a monument by Suchkov was erected on the grave. According to the will drawn up back in 1969, Shalamov bequeathed all his property, including the rights to his works, to Irina Sirotinskaya.

Family

Varlam Shalamov was married twice: the first time in 1934-1956 – to Galina Ignatyevna Gudz (1909-1986), in this marriage a daughter Elena was born (married name Yanushevskaya, 1935-1990)

The second marriage in 1956-1966 – to the writer Olga Sergeevna Neklyudova (1909-1989). Stepson (Neklyudova’s son from a previous marriage) – philologist and orientalist Sergei Yuryevich Neklyudov (born 1941). After the death of Irina Sirotinskaya, the rights to Shalamov’s works belong to her son, popularizer and researcher of Shalamov Alexander Leonidovich Rigosik.

History of publications and recognition

The life’s work of Varlam Shalamov is considered to be the cycle “Kolyma Tales”, consisting of six collections of stories and essays (“Kolyma Tales”, “Left Bank”, “Artist of the Spade”, “Essays on the Criminal World”, “Resurrection of the Larch” and “The Glove, or KR-2”, written in 1954-1973). Shalamov insisted that the complete works are precisely the collections that preserve the order in which the stories are arranged. He wrote: “Compositional integrity is a significant quality of “Kolyma Tales”. In this collection, only a few stories can be replaced and rearranged, but the main, supporting ones must stand in their places. Everyone who read “Kolyma Tales” as a whole book, and not individual stories, noted a great, powerful impression. All readers say this. This is explained by the non-randomness of the selection, careful attention to the composition.” Shalamov’s bibliography also includes the autobiographical works “The Fourth Vologda” and the “anti-novel” “Vishera”, the plays “Anna Ivanovna” and “Evening Conversations”, a collection of memoirs and essays, and a corpus of poems.

Individual poems by Shalamov from “Kolyma Notebooks” were published in magazines in the late 1950s; since 1961, five poetry collections have been published in the Soviet Union, including a total of about three hundred poems out of about 1,300 known ones. During the writer’s lifetime, “Kolyma Tales” were published only abroad. International recognition (but not yet royalties) came to Shalamov when he was already dying in a nursing home, with the first American editions of “Kolyma Tales” (1980) and “Graphite” (1981), both translated by John Glad. In an early review in the Inquiry, Anthony Burgess argued: “In terms of content as such, there is nothing in Shalamov that would add anything new to our indignation.

We have had our fill of horrors. The wonder of Shalamov’s stories lies in the stylistic effects and artistic selection, not in the anger and bitterness with which they are filled. The initial conditions are a comprehensive injustice that cannot be a subject of condemnation for the artist, and survival in circumstances where death is preferable.” Shalamov’s prose, since it became known in the West, has entered the canon of “witness” literature of the 20th century – documentary and fictional prose by European authors who survived the Holocaust and Nazi death camps (Primo Levi, Elie Wiesel, Imre Kertész, Jorge Semprun, Tadeusz Borowski), who solved similar problems – to find expressive means to describe a terrible, unimaginable and indescribable experience. Semprun did much to popularize the “Kolyma Tales” in the West, and Levi reviewed their Italian translation. In 1981, the French branch of the PEN Club awarded Shalamov the Freedom Prize. The first Soviet publications of the collections of stories took place in 1989, the cycle was published in Russia in two volumes in 1992. “Kolyma Notebooks” were published under the editorship of I. Sirotinskaya in 1994, Shalamov’s complete poetic corpus, including poems written in the late 1940s – early 1950s in the Duskanya spring and in Yakutia, and poems from the 1960s, known only from audio recordings, was published in 2020 in two volumes under the editorship of V. Esipov.

Prose. “Kolyma Tales”

Shalamov’s name is associated primarily with the form of the story – a compressed, concentrated statement. Wolfgang Kazak defines the main properties of Shalamov’s story as follows: its plot is limited to one incident experienced by the author himself; the description is precise and devoid of “stylistic subtleties”; the impression is created by “the depiction of the very cruelty, inhumanity of what is happening.” Elena Mikhailik formulates the elements of Shalamov’s intonation as “a slow, strictly objectified narration, slightly shifted by either a barely perceptible black irony or a brief emotional outburst.” Gennady Aygi wrote about the form chosen by Shalamov, using the example of the story “The Green Prosecutor”, that in it “some special, previously unexistent large form of prose (not a novel, not a study, not a story… – some large abstract-pure correspondence to the “unnoveled” tragedy of time) is visible.” The language of Shalamov’s stories is distinguished by musicality, the presence of rhythm and distinct changes in tempo, the use of repetitions and alliterations, which give the prose a dissonant sound.

Shalamov considered the Kolyma camps, combining harsh climatic conditions and the hard labor of prisoners, to be the embodiment of absolute evil: “It is terrible to see a camp, and not a single person in the world should know camps. The camp experience is entirely negative to the last minute. A person only gets worse. And it cannot be otherwise …” (“Engineer Kiselyov”), “A camp is a completely and utterly negative school of life. No one will take anything useful or necessary from there. <…> There is much there that a person should not know, should not see, and if he has seen it, it is better for him to die” (“Red Cross”). Shalamov describes the camp as circumstances of extreme dehumanization, in which a person loses everything that makes him an individual, including the properties of language and memory, and is reduced to purely physiological processes, a mechanical existence. The author of “Kolyma Tales” does not pay attention to the psychological development of his characters, but only shows their behavior in the exceptional circumstances where they are placed, when survival is at stake.

This was also one of the points of his polemic with Solzhenitsyn: he offered a more optimistic view, in which the camp can also be a source of new knowledge and a better understanding of life. At the same time, V. Babitskaya notes that Shalamov’s stories themselves provide a gallery of characters who have retained a moral core and the ability to show kindness and mercy. Klaus Stedtke calls the state of constant proximity to death, finitude and, in general, the meaninglessness of life, in which Shalamov’s characters exist, the end of humanism. Andrei Sinyavsky characterizes “Kolyma Tales” as written “in the face of life”: “Having survived life, a person asks himself: why are you alive? In the Kolyma situation, all life is egoism, sin, murder of a neighbor, whom you surpassed only by remaining alive. And life is meanness. Living is generally indecent. A survivor in these conditions will forever have a sediment of “life” in his soul as something shameful, disgraceful. “Why didn’t you die?” is the last question that is put to a person… Indeed: why am I still alive when everyone else has died?..”

In his programmatic essay “On Prose,” Shalamov wrote: “The novel is dead. And no force in the world will resurrect this literary form.” He condemned the “puffy, verbose descriptiveness,” the skillfully composed story, and the detailed portrayal of characters who, from his point of view, did not prevent Kolyma and Auschwitz. Shalamov sought adequate form and expressive means to describe the experience of the camps and eventually arrived at what he himself characterized as “new prose”: “New prose is the event itself, the battle, and not its description. That is, a document, the author’s direct participation in the events of life. Prose experienced as a document.” In another place he stated: “When I am asked what I write, I answer: I do not write memoirs. There are no memoirs in the Kolyma Tales.

I do not write stories either – or rather, I try to write not a story, but something that would not be literature. Not the prose of a document, but prose that has been suffered as a document.” Interpreting these words, Valery Podoroga considers Shalamov’s method as a concession to the artistic to the detriment of testimony: “Increasingly sophisticated techniques of literary writing prevent prose from turning into a document. In “Kolyma Tales” there is invariably a craving for highly artistic execution, an aesthetic feeling, a certain additive that weakens the effect of truth (reliability). Sometimes the wrong, alien words and combinations appear, aesthetically justified, but somewhat decorative, distracting the reader.” Mikhailik objects to Podoroga, she considers “Kolyma Tales” as the completed result of Shalamov’s search as a writer for a new language that could describe what had not previously been understood by culture, and which was not supposed to be pure testimony. She sees a direct continuity between Shalamov’s prose and Sergei Tretyakov’s theory of “literature of fact”, but with the difference that in order to more clearly convey the inhuman conditions that arise in the camps, Shalamov writes not a document, but fiction, the impression of which “would coincide with the impression of the experienced reality”. At the same time, the writer declared, for example, that all the murderers in his stories were given their real names. Historian Arseny Roginsky, calling “Kolyma Tales” “great prose that has stood the test of a document”, noted that, while making mistakes, for example, in the ranks and positions of the people he met, Shalamov very accurately described precisely those legal procedures and practices that existed in the Kolyma camps during the time the stories were set. Such researchers of Stalin’s camps as Robert Conquest and Anne Applebaum, realizing that they were dealing with a literary work, nevertheless used the stories as a primary source.

Another feature of the Kolyma Tales is their intertextuality and polyphony, which, when reading the cycle sequentially, create the effect that reality is simultaneously supplemented and eludes: events are repeated, the voices of the narrator, whose name is sometimes Andreyev, sometimes Golubev, sometimes Krist, sometimes Shalamov, are intertwined; the first person in the narrative is replaced by the third; the narrator with incomplete knowledge is replaced by the omniscient narrator. The coexistence of stories within the cycle allows us to trace how the same story or the fate of the same character, described in one story, is developed, given a background or confirmed, or, on the contrary, is refuted in another story. Toker and Mikhailik consider this technique primarily as the author’s rendering of the state of personality disintegration in the camp: when the prisoner’s only real concern is survival, his memory is impaired, and the events described could have happened to any person or to all at once.

The main reality becomes the fact of death itself, and not its specific circumstances. In the words of Varvara Babitskaya, Shalamov speaks from a mass grave. In an article from 1999, Solzhenitsyn, analyzing this technique, once again stated his fundamental disagreement with the author: “True, Shalamov’s stories did not satisfy me artistically: in all of them I lacked characters, faces, the past of these faces and some kind of separate view of life for each. In the stories <…> there were not specific special people, but almost only surnames, sometimes repeating themselves from story to story, but without the accumulation of individual traits.

To suppose that this was Shalamov’s intention: the most brutal camp routine wears out and crushes people, people cease to be individuals, but only sticks that the camp uses? Of course, he wrote about extreme suffering, extreme detachment from personality – and everything is reduced to the struggle for survival. But, firstly, I do not agree that all the traits of personality and past life are destroyed so completely: this does not happen, and something personal must be shown in everyone. And secondly, Shalamov went through this too clearly, and I see a flaw in his pen here. Yes, in “Funeral Oration” he seems to decipher that in all the heroes of all the stories there is himself. And then it is clear why they are all in the same boat. And the variable names are only an external device to hide the biographical nature.”

At the same time as the later “Kolyma Tales”, at the turn of the 1960s and 1970s, Shalamov wrote “Vishera Anti-Novel”, also organized as a cycle of short, complete stories and essays, but in it he chose a different angle: in all the components of the “anti-novel” the narrator is Varlam Shalamov, as he remembered himself in 1929.

According to Mikhailik, “this inattentive narrator, squeezed in the vice of clichés and limited by his own idea of himself, is extremely biased and extremely blind to everything that goes beyond his beliefs and experience.” In some cases, this can be seen by comparing the description of events and people in the “anti-novel” with their description in the “Vishera” “Kolyma Tales”, where the true attitude of Shalamov the author is revealed. Mikhailik concludes that Shalamov, having set himself the task of seeing what he saw in 1929 while writing the “anti-novel,” and not seeing, missing what he was able to comprehend only later, won as a literary theorist and lost as a writer: a reader who gets acquainted with the “anti-novel” without taking into account the optics of the “Kolyma Tales” will find nothing but a rather superficial documentary.

Shalamov defined himself as the heir “not of the humane Russian literature of the 19th century, but <…> of the modernism of the beginning of the century.” In his notebooks, he cites his dialogue with Nikolai Otten: “Otten: You are the direct heir of all Russian literature — Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Chekhov. — Me: I am the direct heir of Russian modernism — Bely and Remizov. I studied not with Tolstoy, but with Bely, and in each of my stories there are traces of this study.” Shalamov considered the belief that virtue is inherent in human nature, in self-improvement through the search for truth and suffering, and that it is the “common people” who are closest to possessing this highest truth to be a fundamental mistake of the 19th century novelists, the result of which was, among other things, terror against the intelligentsia. However, if he categorically rejected Tolstoy, then Shalamov’s attitude to Dostoevsky was multifaceted: he wrote a lot about Dostoevsky’s genius and the enduring relevance of his novels in the era of “two world wars and revolutions,” but he also criticized a lot. Not the least of these is the polemic with “Notes from the House of the Dead”: Dostoevsky’s penal experience, in Shalamov’s opinion, nevertheless did not allow him to understand the essence of professional criminals (“blatarei”), and here Dostoevsky repeated the general mistake of Russian literature. In his notebooks, Shalamov summed up: “In our day, Dostoevsky would not have repeated the phrase about the God-bearing people.” In Mikhail Zoshchenko, an older contemporary and also a master of the short story, Shalamov singled out the same features that he honed in his prose: “Zoshchenko was successful because he was not a witness, but a judge, a judge of time. <…> Zoshchenko was the creator of a new form, a completely new way of thinking in literature (the same feat as Picasso, who removed three-dimensional perspective), showing new possibilities of the word.” Speaking about the “end of humanism” in Shalamov, Städtke notes his closeness to the existentialism of the absurdity of Albert Camus.

Poetry

“The Instrument” (from the collection “Golden Mountains”). Shalamov repeatedly turned to Dante Alighieri as a poet who left an exemplary description of hell. Shalamov formulated his aesthetic credo as follows: “The best that Russian poetry has to offer is late Pushkin and early Pasternak.” Shalamov’s poetry, syllabo-tonic, based on rhythm and rhyme, mostly written in iambic or trochee with division into quatrains, is generally considered to be quite traditional for Russian versification, even somewhat archaic (Leona Toker writes that his poems could seem like an anachronism even against the backdrop of Yevtushenko). At the same time, Vyacheslav Ivanov claimed that Shalamov’s iambic tetrameter differs from the traditional one and that “his poetry strives for originality in size, meter, rhythm and rhyme, which he so amazingly told Pasternak about – rhyme as a way of searching for something new not only in the form of verse, but in the essence of what he writes.” In accordance with his own ideas about the theory of poetry, Shalamov built his poems on a kind of sound framework – on repeating consonants that were to be contained in words that were key to understanding the images. Shalamov’s poetry is best known for its descriptions of the harsh Kolyma landscapes, but is not limited to them, and includes love lyrics and reflections on history and culture. His poems, according to Kazak, “reflect the bitterness of his life experience in a simple and not particularly condensed form”, they are full of longing for humanity, and the main images in them are snow, frost and, as a consolation, sometimes deceptive, – fire.

K. Lvov sees in Shalamov, who placed man surrounded by the elements and actively used images of nature in metaphors, on the one hand, a continuer of the tradition of philosophical landscape lyrics of Derzhavin and Fet, and on the other, a “comrade in natural philosophy” of Zabolotsky and the OBERIUTs. Georgy Adamovich, reviewing “The Road and Fate,” wrote that it was “difficult for him to get rid of the ‘Kolyma’ approach” to Shalamov’s poetry: “Perhaps, at least in the main, the dryness and severity of these poems are an inevitable consequence of the loneliness of the camp <…>?” Adamovich concluded that in Shalamov “the illusions that so often turn out to be the essence and core of lyricism have dissipated.” One of Shalamov’s favorite historical figures was Archpriest Avvakum, to whom he dedicated the quatrain “Still the Same Snows of Avvakum’s Century” written in 1950 on the key of Duskanye and the programmatic poem “Avvakum in Pustozersk” (1955). He found many parallels between his fate and the fate of the ideologist of the Schism: persecution for his beliefs, many years of imprisonment in the distant North, the autobiographical genre of his works. Works

The Kolyma Tales Cycle (written in 1954-1973)

“Kolyma Tales”

“Left Bank”

“The Artist of the Shovel”

“Essays on the Criminal World”

“Resurrection of the Larch”

“The Glove or KR-2”

Collections of poems from the “Kolyma Notebooks” (written in 1949-1954, partially published in magazines during the author’s lifetime)

“The Blue Notebook”

“The Postman’s Bag”

“Personally and Confidentially”

“Golden Mountains”

“Fireweed”

“High Latitudes”

Collections of poems published during his lifetime

“Flint” (“Soviet Writer”, 1961)

“Rustle of Leaves” (“Soviet Writer”, 1964)

“Road and Fate” (“Soviet Writer”, 1967)

“Moscow Clouds” (“Soviet Writer”, 1972)

“Boiling Point” (“Soviet Writer”, 1977)

Plays (not published during his lifetime)

“Anna Ivanovna” (play)

“Evening Conversations” (play)

Autobiographical prose, memoirs (not published during his lifetime)

“The Fourth Vologda” (story)

“Vishera. Anti-novel” (essay series)

“My Life – Several of My Lives”

“The Twenties”

“Moscow in the 20s – 30s”

Some of Shalamov’s stories and essays that were not included in collections were published during his lifetime in magazines in the 1930s and later, starting in the second half of the 1950s. In the collected works of Shalamov (a four-volume edition prepared by the publishing house “Khudozhestvennaya Literatura”, published with the participation of the publishing house “Vagrius” in 1998, a six-volume edition – in 2004-2005 by the publishing house “Terra – Book Club”, during the re-release in 2013 an additional 7th volume was added, all editions edited by I. P. Sirotinskaya) a significant place is also occupied by his essays, notebooks and letters.

Asteroid 3408 Shalamov, discovered on August 17, 1977 by astronomer Nikolai Chernykh, was named in honor of V. T. Shalamov.

A bronze bust by Fedot Suchkov on a granite pedestal based on a wooden sculptural portrait from his lifetime was installed on Shalamov’s grave. In June 2000, the bust was stolen, probably by scrap metal collectors. In 2001, a cast-iron bust was cast and installed to replace the stolen one.

In 1990, a memorial plaque was installed on the clergy house in Vologda where Shalamov was born, and since 1991, a memorial museum of the writer has been operating in part of the premises. Memorial evenings are held in the house, and every few years, a conference called “Shalamov Readings” is held. There are exhibitions dedicated to Shalamov in the local history museum at the school in Tomtor (Yakutia), where he worked as a paramedic in 1952-1953 (opened in 1992), in the museum in memory of victims of political repression in Yagodnoye, created in 1994 by local historian Ivan Panikarov, and since 2005 in the building of the Magadan Regional Anti-Tuberculosis Dispensary No. 2 in the village of Debin (former Central Hospital for Prisoners of Dalstroy), where Shalamov worked in 1946-1951 (both in the Magadan Region). Since 2013, a memorial plaque has been installed on the dispensary building.

In 1995, a monument to the victims of political repression designed by Mikhail Shemyakin was unveiled in St. Petersburg. One of the plaques on it quotes Shalamov’s story “The Resurrection of the Larch”.

In 2007, a monument to Shalamov by sculptor Rudolf Vedeneyev was erected in Krasnovishersk, which grew up on the site of Vishlag, where the writer served his sentence in 1929-1931. In 2005, a memorial plaque was unveiled on the wall of the Trinity Monastery in Solikamsk, where Shalamov’s convoy stopped on the way to Vishlag.

In 2013, a memorial plaque by sculptor Georgy Frangulyan was unveiled on a house in Moscow’s Chisty Lane, where Gudzei had an apartment and where Shalamov lived for three years before his second arrest. Historian and Memorial employee Irina Shcherbakova[en] noted that the inscription stating that Shalamov lived in this house “between arrests” is the first mention of the repressions on a memorial plaque in Moscow.

In 2013, the Berlin House of Literature opened an exhibition dedicated to Shalamov, “To Live or to Write.” In 2016-2017, it was shown at the International Memorial in Moscow.

In December 2015, the artist Zoom created graffiti depicting a portrait of Varlam Shalamov on a book page on the wall of house No. 9 on 4th Samotechny Lane in Moscow (this house is located near the Gulag History Museum).

In June 2021, the open festival “Fourth Vologda” dedicated to the life and work of Shalamov was held in Vologda. As part of the festival, a new tourist route through Shalamov’s places was presented, developed by the staff of the Vologda Regional Art Gallery.