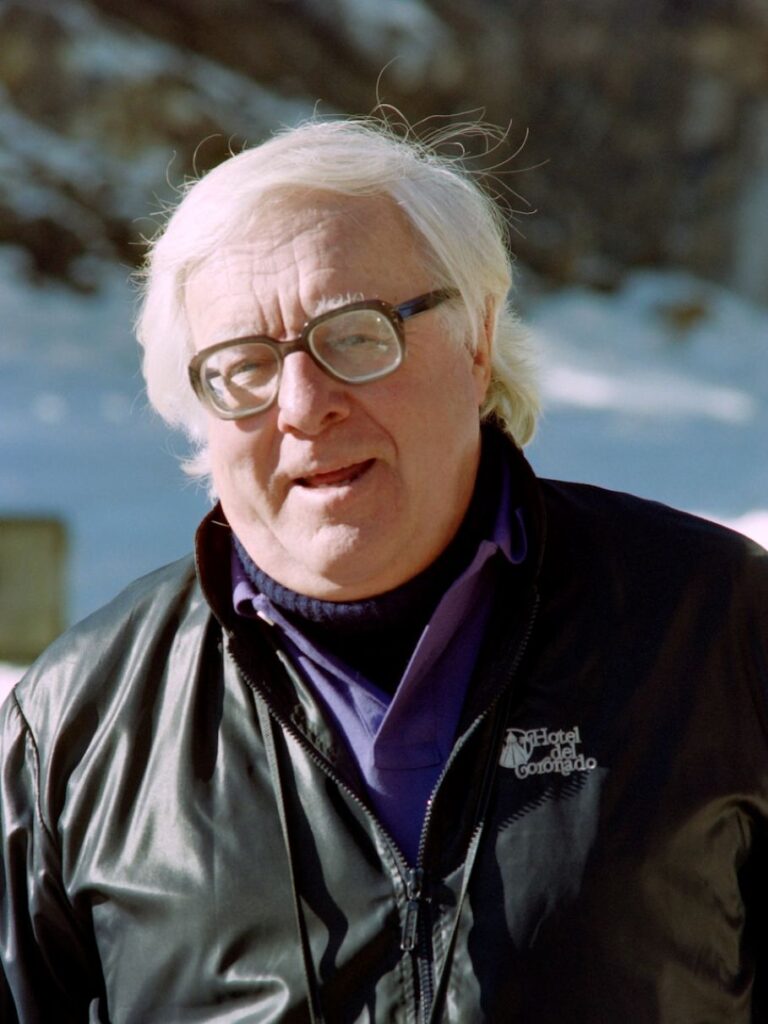

Powerhouse, Ray Bradbury

Powerhouse

The horses moved gently to a stop, and the man and his wife gazed down into a dry, sandy valley.

The woman sat lost in her saddle; she hadn’t spoken for hours, didn’t know a good word to speak.

She was trapped somewhere between the hot, dark pressure of the storm-clouded Arizona sky and the hard, granite pressure of the wind-blasted mountains.

A few drops of cool rain fell on her trembling hands.

She looked over at her husband wearily. He sat his dusty horse easily, with a firm quietness. She closed her eyes and thought of how she had been all of these mild years until today.

She wanted to laugh at the mirror she was holding up to herself, but there was no way of doing even that; it would be somewhat insane.

After all, it might just be the pushing of this dark weather, or the telegram they had taken from the messenger on horseback this morning, or the long journey now to town.

There was still an empty world to cross, and she was cold.

‘I’m the lady who was never going to need religion,’ she said quietly, her eyes shut.

‘What?’ Berty, her husband, glanced over at her.

‘Nothing,’ she whispered, shaking her head. In all the years, how certain she had been. Never, never would she have need of a church. She had heard fine people talk on and on of religion and waxed pews and calla lilies in great bronze buckets and vast bells of churches in which the preacher rang like a clapper.

She had heard the shouting kind and the fervent, whispery kind, and they were all the same. Hers was simply not a pew-shaped spine.

‘I just never had a reason ever to sit in a church,’ she had told people. She wasn’t vehement about it. She just walked around and lived and moved her hands that were pebble-smooth and pebble-small.

Work had polished the nails of those hands with a polish you could never buy in a bottle. The touching of children had made them soft, and the raising of children had made them temperately stern, and the loving of a husband had made them gentle.

And now, death made them tremble.

‘Here,’ said her husband. And the horses dusted down the trail to where an odd brick building stood beside a dry wash. The building was all glazed green windows, blue machinery, red tile, and wires.

The wires ran off on high-tension towers to the farthest directions of the desert. She watched them go, silently, and, still held by her thoughts, turned her gaze back to the strange storm-green windows and the burning-colored bricks.

She had never slipped a ribbon in a Bible at a certain significant verse, because though her life in this desert was a life of granite, sun, and the steaming away of the waters of her flesh, there had never been a threat in it to her. Always things had worked out before the necessity had come for sleepless dawns and wrinkles in the forehead. Somehow, the very poisonous things of life had passed her by. Death was a remote stormrumor beyond the farthest range.

Twenty years had blown in tumbleweeds, away, since she’d come West, worn this lonely trapping man’s gold ring, and taken the desert as a third, and constant, partner to their living. None of their four children had ever been fearfully sick or near death. She had never had to get down on her knees except for the scrubbing of an already well-scrubbed floor.

Now all that was ended. Here they were riding toward a remote town because a simple piece of yellow paper had come and said very plainly that her mother was dying.

And she could not imagine it—no matter how she turned her head to see or turned her mind to look in on itself. There were no rungs anywhere to hold to, going either up or down, and her mind, like a compass left out in a sudden storm of sand, was suddenly blown free of all its once-clear directions, all points of reference worn away, the needle spinning without purpose, around, around. Even with Berty’s arms on her back it wasn’t enough. It was like the end of a good play and the beginning of an evil one. Someone she loved was actually going to die. This was impossible!

‘I’ve got to stop,’ she said, not trusting her voice at all, so she made it sound irritated to cover her fear.

Berty knew her as no irritated woman, so the irritation did not carry over and fill him up. He was a capped jug: the contents there for sure. Rain on the outside didn’t stir the brew. He side-ran his horse to her and took her hand gently. ‘Sure,’ he said. He squinted at the eastern sky. ‘Some clouds piling up black there. We’ll wait a bit. It might rain. I wouldn’t want to get caught in it.’

Now she was irritated at her own irritation, one fed upon the other, and she was helpless. But rather than speak and risk the cycle’s commencing again, she slumped forward and began to sob, allowing her horse to be led until it stood and tramped its feet softly beside the red brick building.

She slid down like a parcel into his arms, and he held her as she turned in on his shoulder; then he set her down and said. ‘Don’t look like there’s people here.’ He called, ‘Hey, there!’ and looked at the sign on the door: DANGER, BUREAU OF ELECTRIC POWER.

There was a great insect humming all through the air. It sang in a ceaseless, bumbling tone, rising a bit, perhaps falling just a bit, but keeping the same pitch. Like a woman humming between pressed lips as she makes a meal in the warm twilight over a hot stove. They could see no movement within the building: there was only the gigantic humming.

It was the sort of noise you would expect the sun-shimmer to make rising from hot railroad ties on a blazing summer day, when there is that flurried silence and you see the air eddy and whorl and ribbon, and expect a sound from the process but get nothing but an arched tautness of the eardrums and the tense quiet.

The humming came up through her heels, into her medium-slim legs, and thence to her body. It moved to her heart and touched it, as the sight of Berty just sitting on a top rail of the corral often did. And then it moved on to her head and slenderest niches in the skull and set up a singing, as love songs and good books had done once on a time.

The humming was everywhere. It was as much a part of the soil as the cactus. It was as much a part of the air as the heat.

‘What is it?’ she asked, vaguely perplexed, looking at the building.

‘I don’t know much about it except it’s a powerhouse,’ said Berty. He tried the door. ‘It’s open,’ he said, surprised. ‘I wish someone was around.’ The door swung wide and the pulsing hum came out like a breath of air over them, louder.

They entered together into the solemn, singing place. She held him tightly, arm in arm.

It was a dim undersea place, smooth and clean and polished, as if something or other was always coming through and coming through and nothing ever stayed, but always there was motion and motion, invisible and stirring and never settling. On each side of them as they advanced were what first appeared to be people standing quietly, one after the other, in a double line.

But these resolved into round, shell-like machines from which the humming sprang.

Each black and gray and green machine gave forth golden cables and lime-colored wires, and there were silver metal pouches with crimson tabs and white lettering, and a pit like a washtub in which something whirled as if rinsing unseen materials at invisible speeds. The centrifuge raced so fast it stood still.

Immense snakes of copper looped down from the twilight ceiling, and vertical pipes webbed up from cement floor to fiery brick wall. And the whole of it was as clean as a bolt of green lightning and smelled similarly.

There was a crackling, eating sound, a dry rustling as of paper; flickers of blue fire shuttled, snapped, sparked, hissed where wires joined procelain bobbins and green glass insulation.

Outside, in the real world, it began to rain.

She didn’t want to stay in this place; it was no place to stay, with its people that were not people but dim machines and its music like an organ caught and pressed on a low note and a high note. But the rain washed every window and Berty said, ‘Looks like it’ll last. Might have to stay the night here. It’s late anyhow. I’d better get the stuff in.’

She said nothing. She wanted to be getting on. Getting on to what thing in what place, there was really no way of knowing.

But at least in town she would hold on to the money and buy the tickets and hold them tight in her hand and hold on to a train which would rush and make a great noise, and get off the train, and get on another horse, or get into a car hundreds of miles away and ride again, and stand at last by her dead or alive mother.

It all depended on time and breath. There were many places she would pass through, but none of them would offer a thing to her except ground for her feet, air