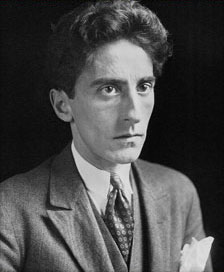

Jean Maurice Eugène Clément Cocteau (UK: /ˈkɒktoʊ/ KOK-toh, US: /kɒkˈtoʊ/ kok-TOH, French: [ʒɑ̃ mɔʁis øʒɛn klemɑ̃ kɔkto]; 5 July 1889 – 11 October 1963) was a French poet, playwright, novelist, designer, film director, visual artist and critic. He was one of the foremost artists of the surrealist, avant-garde, and Dadaist movements and an influential figure in early 20th century art. The National Observer suggested that, “of the artistic generation whose daring gave birth to Twentieth Century Art, Cocteau came closest to being a Renaissance man.”.

He is best known for his novels Le Grand Écart (1923),

Le Livre blanc (1928),

Les Enfants Terribles (1929); the stage plays La Voix Humaine (1930),

La Machine Infernale (1934),

Les Parents terribles (1938),

La Machine à écrire (1941),

L’Aigle à deux têtes (1946); and the films The Blood of a Poet (1930),

Les Parents Terribles (1948),

Beauty and the Beast (1946),

Orpheus (1950),

Testament of Orpheus (1960), which alongside Blood of a Poet and Orpheus constitute the so-called Orphic Trilogy.

He was described as “one of the avant-garde’s most successful and influential filmmakers” by AllMovie. Cocteau, according to Annette Insdorf, “left behind a body of work unequalled for its variety of artistic expression.”

Though his body of work encompassed many different mediums, Cocteau insisted on calling himself a poet, classifying the great variety of his works – poems, novels, plays, essays, drawings, films – as “poésie”, “poésie de roman”, “poésie de thêatre”, “poésie critique”, “poésie graphique” and “poésie cinématographique”.

Early life

Cocteau was born in Maisons-Laffitte, Yvelines, to Georges Cocteau and his wife, Eugénie Lecomte, a socially prominent Parisian family. His father, a lawyer and amateur painter, died by suicide when Cocteau was nine. From 1900 to 1904, Cocteau attended the Lycée Condorcet where he met and began a relationship with schoolmate Pierre Dargelos, who reappeared throughout Cocteau’s work, “John Cocteau: Erotic Drawings.” He left home at fifteen. He published his first volume of poems, Aladdin’s Lamp, at nineteen. Cocteau soon became known in Bohemian artistic circles as The Frivolous Prince, the title of a volume he published at twenty-two. Edith Wharton described him as a man “to whom every great line of poetry was a sunrise, every sunset the foundation of the Heavenly City…”

Early career

In his early twenties, Cocteau became associated with the writers Marcel Proust, André Gide, and Maurice Barrès. In 1912, he collaborated with Léon Bakst on Le Dieu bleu for the Ballets Russes; the principal dancers being Tamara Karsavina and Vaslav Nijinsky. During World War I, Cocteau served in the Red Cross as an ambulance driver. This was the period in which he met the poet Guillaume Apollinaire, artists Pablo Picasso and Amedeo Modigliani, and numerous other writers and artists with whom he later collaborated. Russian impresario Sergei Diaghilev persuaded Cocteau to write a scenario for a ballet, which resulted in Parade in 1917. It was produced by Diaghilev, with sets by Picasso, the libretto by Apollinaire and the music by Erik Satie. “If it had not been for Apollinaire in uniform,” wrote Cocteau, “with his skull shaved, the scar on his temple and the bandage around his head, women would have gouged our eyes out with hairpins.”

An important exponent of avant-garde art, Cocteau had great influence on the work of others, including a group of composers known as Les six. In the early twenties, he and other members of Les six frequented a wildly popular bar named Le Boeuf sur le Toit, a name that Cocteau himself had a hand in picking. The popularity was due in no small measure to the presence of Cocteau and his friends.

Friendship with Raymond Radiguet

In 1918 he met the French poet Raymond Radiguet. They collaborated extensively, socialized, and undertook many journeys and vacations together. Cocteau also got Radiguet exempted from military service. Admiring of Radiguet’s great literary talent, Cocteau promoted his friend’s works in his artistic circle and arranged for the publication by Grasset of Le Diable au corps (a largely autobiographical story of an adulterous relationship between a married woman and a younger man), exerting his influence to have the novel awarded the “Nouveau Monde” literary prize. Some contemporaries and later commentators thought there might have been a romantic component to their friendship. Cocteau himself was aware of this perception, and worked earnestly to dispel the notion that their relationship was sexual in nature.

There is disagreement over Cocteau’s reaction to Radiguet’s sudden death in 1923, with some claiming that it left him stunned, despondent and prey to opium addiction. Opponents of that interpretation point out that he did not attend the funeral (he generally did not attend funerals) and immediately left Paris with Diaghilev for a performance of Les noces (The Wedding) by the Ballets Russes at Monte Carlo. His opium addiction at the time, Cocteau said, was only coincidental, due to a chance meeting with Louis Laloy, the administrator of the Monte Carlo Opera. Cocteau’s opium use and his efforts to stop profoundly changed his literary style. His most notable book, Les Enfants Terribles, was written in a week during a strenuous opium weaning. In Opium: Journal of drug rehabilitation, he recounts the experience of his recovery from opium addiction in 1929. His account, which includes vivid pen-and-ink illustrations, alternates between his moment-to-moment experiences of drug withdrawal and his current thoughts about people and events in his world. Cocteau was supported throughout his recovery by his friend and correspondent, Catholic philosopher Jacques Maritain. Under Maritain’s influence Cocteau made a temporary return to the sacraments of the Catholic Church. He again returned to the Church later in life and undertook a number of religious art projects.

Further works

On 15 June 1926 Cocteau’s play Orphée was staged in Paris. It was quickly followed by an exhibition of drawings and “constructions” called Poésie plastique–objets, dessins. Cocteau wrote the libretto for Igor Stravinsky’s opera-oratorio Oedipus rex, which had its original performance in the Théâtre Sarah Bernhardt in Paris on 30 May 1927. In 1929 one of his most celebrated and well known works, the novel Les Enfants terribles was published

In 1930 Cocteau made his first film The Blood of a Poet, publicly shown in 1932. Though now generally accepted as a surrealist film, the surrealists themselves did not accept it as a truly surrealist work. Although this is one of Cocteau’s best known works, his 1930s are notable rather for a number of stage plays, above all La Voix humaine and Les Parents terribles, which was a popular success. His 1934 play La Machine infernale was Cocteau’s stage version of the Oedipus legend and is considered to be his greatest work for the theater. During this period Cocteau also published two volumes of journalism, including Mon Premier Voyage: Tour du Monde en 80 jours, a neo-Jules Verne around the world travel reportage he made for the newspaper Paris-Soir.

1940–1944

Throughout his life, Cocteau tried to maintain a distance from political movements, confessing to a friend that “my politics are non-existent.” According to Claude Arnaud, from the 1920s on, Cocteau’s only deeply held political convictions were a marked pacifism and antiracism. He praised the French republic for serving as a haven for the persecuted, and applauded Picasso’s anti-war painting Guernica as a cross that “Franco would always carry on his shoulder.” In 1940, Cocteau signed a petition circulated by the Ligue internationale contre l’antisémitisme (International League Against Antisemitism) which protested the rise of racism and antisemitism in France, and declared himself “ashamed of his white skin” after witnessing the plight of colonized peoples during his travels.

Although in 1938 Cocteau had compared Adolf Hitler to an evil demiurge who wished to perpetrate a Saint Bartholomew’s Day massacre against Jews, his friend Arno Breker convinced him that Hitler was a pacifist and patron of the arts with France’s best interests in mind. During the Nazi occupation of France, he was in a “round-table” of French and German intellectuals who met at the Georges V Hotel in Paris, including Cocteau, the writers Ernst Jünger, Paul Morand and Henry Millon de Montherlant, the publisher Gaston Gallimard and the Nazi legal scholar Carl Schmitt. In his diary, Cocteau accused France of disrespect towards Hitler and speculated on the Führer’s sexuality. Cocteau effusively praised Breker’s sculptures in an article entitled ‘Salut à Breker’ published in 1942. This piece caused him to be arraigned on charges of collaboration after the war, though he was cleared of any wrongdoing and had used his contacts for his failed attempt to save friends such as Max Jacob. Later, after growing closer with communists such as Louis Aragon, Cocteau would name Joseph Stalin as “the only great politician of the era.”

In 1940, Le Bel Indifférent, Cocteau’s play written for and starring Édith Piaf (who died the day before Cocteau), was enormously successful.

Later years

Cocteau’s later years are mostly associated with his films. Cocteau’s films, most of which he both wrote and directed, were particularly important in introducing the avant-garde into French cinema and influenced to a certain degree the upcoming French New Wave genre.

Following The Blood of a Poet (1930), his best known films include Beauty and the Beast (1946), Les Parents terribles (1948), and Orpheus (1949). His final film, Le Testament d’Orphée (The Testament of Orpheus) (1960), featured appearances by Picasso and matador Luis Miguel Dominguín, along with Yul Brynner, who also helped finance the film.

In 1945 Cocteau was one of several designers who created sets for the Théâtre de la Mode. He drew inspiration from filmmaker René Clair while making Tribute to René Clair: I Married a Witch. The maquette is described in his “Journal 1942–1945”, in his entry for 12 February 1945:

I saw the model of my set. Fashion bores me, but I am amused by the set and fashion placed together. It is a smoldering maid’s room. One discovers an aerial view of Paris through the wall and ceiling holes. It creates vertigo. On the iron bed lies a fainted bride. Behind her stand several dismayed ladies. On the right, a very elegant lady washes her hands in a flophouse basin. Through the unhinged door on the left, a lady enters with raised arms. Others are pushed against the walls. The vision provoking this catastrophe is a bride-witch astride a broom, flying through the ceiling, her hair and train streaming.

In 1956 Cocteau decorated the Chapelle Saint-Pierre in Villefranche-sur-Mer with mural paintings. The following year he also decorated the marriage hall at the Hôtel de Ville in Menton.

Private life

Jean Cocteau never hid his bisexuality. He was the author of the mildly homoerotic and semi-autobiographical Le Livre blanc (translated as The White Paper or The White Book), published anonymously in 1928. He never repudiated its authorship and a later edition of the novel features his foreword and drawings. The novel begins:

As far back as I can remember, and even at an age when the mind does not yet influence the senses, I find traces of my love of boys. I have always loved the strong sex that I find legitimate to call the fair sex. My misfortunes came from a society that condemns the rare as a crime and forces us to reform our inclinations.

Frequently his work, either literary (Les enfants terribles), graphic (erotic drawings, book illustration, paintings) or cinematographic (The Blood of a Poet, Orpheus, Beauty and the Beast), is pervaded with homosexual undertones, homoerotic imagery/symbolism or camp. In 1947 Paul Morihien published a clandestine edition of Querelle de Brest by Jean Genet, featuring 29 very explicit erotic drawings by Cocteau. In recent years several albums of Cocteau’s homoerotica have been available to the general public.

In the 1930s, Cocteau is rumoured to have had a very brief affair with Princess Natalie Paley, the daughter of a Romanov Grand Duke and herself a sometime actress, model, and former wife of couturier Lucien Lelong.

Cocteau’s longest-lasting relationships were with French actors Jean Marais and Édouard Dermit, whom Cocteau formally adopted. Cocteau cast Marais in The Eternal Return (1943), Beauty and the Beast (1946), Ruy Blas (1947), and Orpheus (1949).

Death

Cocteau died of a heart attack at his château in Milly-la-Forêt, Essonne, France, on 11 October 1963 at the age of 74. His friend, French singer Édith Piaf, died the day before but that was announced on the morning of Cocteau’s day of death; it has been said, in a story which is almost certainly apocryphal, that his heart failed upon hearing of Piaf’s death. Cocteau’s health had already been in decline for several months, and he had previously had a severe heart attack on 22 April 1963. A more plausible suggestion for the reason behind this decline in health has been proposed by author Roger Peyrefitte, who notes that Cocteau had been devastated by a breach with his longtime friend, socialite and notable patron Francine Weisweiller, as a result of an affair she had been having with a minor writer. Weisweiller and Cocteau did not reconcile until shortly before Cocteau’s death.

According to his wishes Cocteau is buried beneath the floor of the Chapelle Saint-Blaise des Simples in Milly-la-Forêt. The epitaph on his gravestone set in the floor of the chapel reads: “I stay with you” (“Je reste avec vous”).

Honours and awards

In 1955, Cocteau was made a member of the Académie Française and The Royal Academy of Belgium.

During his life, Cocteau was commander of the Legion of Honor, Member of the Mallarmé Academy, German Academy (Berlin), American Academy, Mark Twain (U.S.A) Academy, Honorary President of the Cannes Film Festival, Honorary President of the France-Hungary Association and President of the Jazz Academy and of the Academy of the Disc.

Works

Poetry

1909: La Lampe d’Aladin

1910: Le Prince frivole

1912: La Danse de Sophocle

1919: Ode à Picasso – Le Cap de Bonne-Espérance

1920: Escale. Poésies (1917–1920)

1922: Vocabulaire

1923: La Rose de François – Plain-Chant

1925: Cri écrit

1926: L’Ange Heurtebise

1927: Opéra

1934: Mythologie

1939: Énigmes

1941: Allégories

1945: Léone

1946: La Crucifixion

1948: Poèmes

1952: Le Chiffre sept – La Nappe du Catalan (in collaboration with Georges Hugnet)

1953: Dentelles d’éternité – Appoggiatures

1954: Clair-obscur

1958: Paraprosodies

1961: Cérémonial espagnol du Phénix – La Partie d’échecs

1962: Le Requiem

1968: Faire-Part (posthume)

Novels

1919: Le Potomak (definitive edition: 1924)

1923: Le Grand Écart and Thomas l’imposteur

1928: Le Livre blanc

1929: Les Enfants terribles

1940: La Fin du Potomak

Theatre

1917: Parade, ballet (music by Erik Satie, choreography by Léonide Massine)

1921: Les mariés de la tour Eiffel, ballet (music by Georges Auric, Arthur Honegger, Darius Milhaud, Francis Poulenc and Germaine Tailleferre)

1922: Antigone

1924: Roméo et Juliette

1925: Orphée

1927: Oedipus Rex, opera-oratorio (music by Igor Stravinsky)

1930: La Voix humaine

1934: La Machine infernale

1936: L’École des veuves

1937: Œdipe-roi. Les Chevaliers de la Table ronde, premiere at the Théâtre Antoine

1938: Les Parents terribles, premiere at the Théâtre Antoine

1940: Le bel indifférent

1940: Les Monstres sacrés

1941: La Machine à écrire

1943: Renaud et Armide. L’Épouse injustement soupçonnée

1944: L’Aigle à deux têtes

1946: Le Jeune Homme et la Mort, ballet by Roland Petit

1948: Théâtre I and II

1951: Bacchus

1960: Nouveau théâtre de poche

1962: L’Impromptu du Palais-Royal

1971: Le Gendarme incompris (in collaboration with Raymond Radiguet and Francis Poulenc)

Poetry and criticism

1918: Le Coq et l’Arlequin

1920: Carte blanche

1922: Le Secret professionnel

1926: Le Rappel à l’ordre – Lettre à Jacques Maritain – Le Numéro Barbette

1930: Opium

1932: Essai de critique indirecte

1935: Portraits-Souvenir

1937: Mon premier voyage (Around the World in 80 Days)

1943: Le Greco

1946: La Mort et les Statues (photos by Pierre Jahan)

1947: Le Foyer des artistes – La Difficulté d’être

1949: Lettres aux Américains – Reines de la France

1951: Jean Marais – A Discussion about Cinematography (with André Fraigneau)

1952: Gide vivant

1953: Journal d’un inconnu. Démarche d’un poète

1955: Colette (Discourse on the reception at the Royal Academy of Belgium) – Discourse on the reception at the Académie Française

1956: Discours d’Oxford

1957: Entretiens sur le musée de Dresde (with Louis Aragon) – La Corrida du 1er mai

1950: Poésie critique I

1960: Poésie critique II

1962: Le Cordon ombilical

1963: La Comtesse de Noailles, oui et non

1964: Portraits-Souvenir (posthumous; A discussion with Roger Stéphane)

1965: Entretiens avec André Fraigneau (posthumous)

1973: Jean Cocteau par Jean Cocteau (posthumous; A discussion with William Fielfield)

1973: Du cinématographe (posthumous). Entretiens sur le cinématographe (posthumous)

Journalistic poetry

1935–1938 (posthumous)

Film

1925: Jean Cocteau fait du cinéma lost

1930: Le Sang d’un poète

1946: La Belle et la Bête

1948: L’Aigle à deux têtes

1948: Les Parents terribles

1950: Orphée

1950: Coriolan unreleased home movie

1952: La Villa Santo-Sospir

1955: L’Amour sous l’électrode

1957: 8 × 8: A Chess Sonata in 8 Movements

1960: Le Testament d’Orphée

Scriptwriter

1943: L’Éternel Retour directed by Jean Delannoy

1944: Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne directed by Robert Bresson

1948: Ruy Blas directed by Pierre Billon

1950: Les Enfants terribles directed by Jean-Pierre Melville, script by Jean Cocteau based on his novel

1951: La Couronne Noire directed by Luis Saslavsky

1961: La Princesse de Clèves directed by Jean Delannoy

1965: Thomas l’imposteur directed by Georges Franju, script by Jean Cocteau based on his novel

Dialogue writer

1943: Le Baron fantôme (+ actor) directed by Serge de Poligny

1961: La Princesse de Clèves directed by Jean Delannoy

1965: Thomas l’imposteur directed by Georges Franju

Director of Photography

1950: Un chant d’amour réalisé par Jean Genet

Artworks

1924: Dessins

1925: Le Mystère de Jean l’oiseleur

1926: Maison de santé

1929: 25 dessins d’un dormeur

1935: 60 designs for Les Enfants Terribles

1940: Le combattant

1941: Drawings in the margins of Chevaliers de la Table ronde

1948: Drôle de ménage

1957: La Chapelle Saint-Pierre, Villefranche-sur-Mer

1958: La Salle des mariages, City Hall of Menton – La Chapelle Saint-Pierre (lithographies)

1958: Un Arlequin (The Harlequin)

1959: Gondol des morts

1960: Chapelle Saint-Blaise-des-Simples, Milly-la-Forêt

1960: Stained glass windows of the Church of Saint Maximin, Metz, France