To the point that, just as the reader eventually escapes the control of the work, so does the work eventually escape everybody’s control, including that of the author, and starts blabbing away like a crazed computer. What remains then is no longer a field of possibilities but rather the indistinct, the primary, the indeterminate at its wildest—at once everything and nothing.

Audiberti speaks of a sort of “cybernetics,” a word that brings me back to the heart of the matter and to my main question: What, indeed, are the possibilities of communication of this kind of open work?

Openness and Information

In its mathematical formulations (but not necessarily in its application to cybernetics), information theory makes a radical distinction between “meaning” and “information.” The meaning of a message (and by “message” here I also mean a pictorial configuration, even though the way such a configuration communicates is not by means of semantic references but rather by means of formal connections) is a function of the order, the conventions, and the redundancy of its structure. The more one respects the laws of probability (the preestablished principles that guide the organization of a message and are reiterated via the repetition of foreseeable elements), the clearer and less ambiguous its meaning will be. Conversely, the more improbable, ambiguous, unpredictable, and disordered the structure, the greater the information—here understood as potential, as the inception of possible orders.

Certain forms of communication demand meaning, order, obviousness—namely, all those forms which, having a practical function (such as a letter or a road sign), need to be understood univocally, with no possibility for misunderstanding or individual interpretation. Others, instead, seek to convey to their readers sheer information, an unchecked abundance of possible meanings. This is the case with all sorts of artistic communications and aestheticeffects.

As I have already mentioned, the value of every form of art, no matter how conventional or traditional its tools, depends on the degree of novelty present in the organization of its elements—novelty that inevitably entails an increase of information. But whereas “classical” art avails itself of sudden deviations and temporary ruptures only so as to eventually reconfirm the structures accepted by the common sensibility it addresses, thereby opposing certain laws of redundancy only to reendorse them again later, albeit in a different fashion, contemporary art draws its main value from a deliberate rupture with the laws of probability that govern common language—laws which it calls into question even as it uses them for its subversiveends.

When Dante writes, “Fede a sustanzia di cose sperate” (“Faith is the substance of hope”), he adopts the grammatical and syntactic laws of the language of his time to communicate a concept that has already been accepted by the theology of that time. However, to give greater meaning to the communication, he organizes his carefully selected terms according to unusual laws and uncommon connections. By indissolubly fusing the semantic content of the expression with its overall rhythm, he turns what could have been a very common sentence into something completely new, untranslatable, lively, and persuasive (and, as such, capable of giving its reader a great deal of information—not the kind of information that enriches one’s knowledge of the concepts to which it refers, but rather a kind of aesthetic information that rests on formal value, on the value of the message as an essentially reflexive act of communication.

When Eluard writes, “Ciel dontlai &passe la nuit” (“Sky whose night I’ve left behind”), he basically repeats the operation of his predecessor (that is, he organizes sense and sound into a particular form), but his intentions are quite different. He does not want to reassert received ideas and conventional language by lending them a more beautiful or pleasant form; rather, he wants to break with the conventions of accepted language and the usual ways of linking thoughts together, so as to offer his reader a range of possible interpretations and a web of suggestions that are quite different from the kind of meaning conveyed by the communication of a univocal message.

My argument hinges precisely on this plural aspect of the artistic communication, over and above the aesthetic connotations of a message. In the first place, I would like to determine to what extent this desire to join novelty and information in a given message can be reconciled with the possibilities of communication between author and reader. Let’s take a few examples from music.

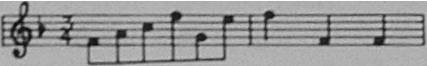

In this short phrase from a Bach minuet (found in the Notenbachlein fur Anna Magdalena Bach,) we can immediately perceive how adhesion to a system of probability and a certain redundancy combine to clarify and univocalize the meaning of the musical message. In this case, the system of probability is that of tonal grammar, the most familiar to a Western postmedieval listener. Here each interval is more than a change in frequency, since it also involves the activation of organic relations within the context.

An ear will always opt for the easiest way to seize these relations, following an “index of rationality” based not only on socalled “objective” perceptual data but also, and above all, on the premises of assimilated linguistic conventions. The first two notes of the first measure make up a perfect F major chord. The next two notes in the same measure (G and E) imply the dominant harmony, whose obvious purpose is to reinforce the tonic by means of the most elementary cadences; in fact, the second measure faithfully returns to the tonic. If this particular minuet began differently, we would have to suspect a misprint. Everything is so clear and linguistically logical that even an amateur could infer, simply by looking at this line, what the eventual harmonic relations (that is to say, the “bass”) of this phrase will be.

This would certainly not be the case with one of Webern’s compositions. In his work, any sequence of sounds is a constella tion with no privileged direction and no univocality. What is missing is a rule, a tonal center, that would allow the listener to predict the development of the composition in a particular direction. The progressions are ambiguous: a sequence of notes may be followed by another, unpredictable one that can be accepted by the listener only after he has heard it. “Harmonically speaking, it would appear that every sound in Webern’s music is closely followed by either one or both of the sounds that, along with it, constitute a chromatic interval.

More often than not, however, this interval is not a halftone, a minor second (still essentially melodic and connective, in its role as leader of the same melodic field); rather, it assumes the form, somewhat stretched, of a major seventh or a minor ninth. Considered as the most elementary links of a relational network, these intervals impede the automatic valorization of the octaves (a process which, given its simplicity, is always within the ear’s reach), cause the meaning of frequential relationships to deviate, and prohibit the imagining of a rectilinear auditive space.””

If a message of this kind is more ambiguous—and therefore more informative—than the previous type, electronic music goes even further in the same direction. Here sounds are fused into “groups” within which it is impossible to hear any relationship among the frequencies (nor does the composer expect as much, preferring, as a rule, that we seize them in a knot, with all its ambiguity and pregnancy). The sounds themselves will consist of unusual frequencies that bear no resemblance to the more familiar musical note and which, therefore, yank the listener away from the auditive world he has previously been accustomed to.

Here, the field of meanings becomes denser, the message opens up to all sorts of possible solutions, and the amount of information increases enormously. But let us now try to take this imprecision—and this information—beyond its outermost limit, to complicate the coexistence of the sounds, to thicken the plot. If we do so, we will obtain “white noise,” the undifferentiated sum of all frequencies— a noise which, logically speaking, should give us the greatest possible amount of information, but which in fact gives us none at all.

Deprived of all indication, all direction, the listener’s ear is no longer capable even of choosing; all it can do is remain passive and impotent in the face of the original chaos. For there is a limit beyond which wealth of information becomes mere noise.

But, of course, even noise can be a signal. Concrete music and, in some cases, electronic music are nothing more than organizations of noise whose order has elevated them to the status of signal. But the transmission of this kind of message poses a problem: “If the sonic material of white noise is formless, what is the minimum ‘personality’ it must have to assume an identity? What is the minimum of spectral form it must have to attain individuality? This is the problem of ‘coloring white noise.'” 12

Something similar also happens with figurative signals. Let us take the example of a Byzantine mosaic, a classic form of redundant communication that lends itself particularly well to this kind of analysis. Every piece of the mosaic can be considered as a unit of information: a bit. The sum of all the pieces will constitute the entire message. But in a traditional mosaic (such as Queen Theodora’s Cortege in the church of San Vitale, in Ravenna), the relationship between one piece and the next is far from casual; it obeys very precise laws of probability. First is the figurative convention whereby the work must represent a human body and a surrounding reality.

Based on a precise model of perception, this convention prompts our eye to connect