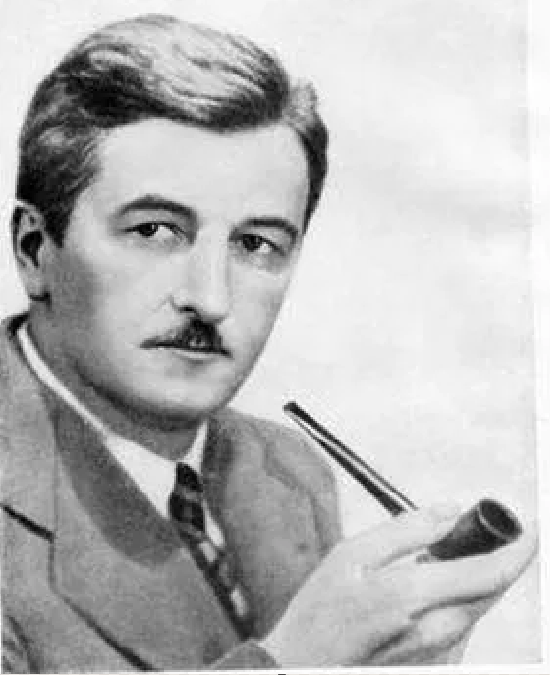

Ad Astra, William Faulkner

Ad Astra

I DONT KNOW what we were. With the exception of Comyn, we had started out Americans, but after three years, in our British tunics and British wings and here and there a ribbon, I dont suppose we had even bothered in three years to wonder what we were, to think or to remember.

And on that day, that evening, we were even less than that, or more than that: either beneath or beyond the knowledge that we had not even wondered in three years. The subadar — after a while he was there, in his turban and his trick major’s pips — said that we were like men trying to move in water.

“But soon it will clear away,” he said. “The effluvium of hatred and of words. We are like men trying to move in water, with held breath watching our terrific and infinitesimal limbs, watching one another’s terrific stasis without touch, without contact, robbed of all save the impotence and the need.”

We were in the car then, going to Amiens, Sartoris driving and Comyn sitting half a head above him in the front seat like a tackling dummy, the subadar, Bland and I in back, each with a bottle or two in his pockets. Except the subadar, that is. He was squat, small and thick, yet his sobriety was colossal.

In that maelstrom of alcohol where the rest of us had fled our inescapable selves he was like a rock, talking quietly in a grave bass four sizes too big for him: “In my country I was prince. But all men are brothers.”

But after twelve years I think of us as bugs in the surface of the water, isolant and aimless and unflagging. Not on the surface; in it, within that line of demarcation not air and not water, sometimes submerged, sometimes not.

You have watched an unbreaking groundswell in a cove, the water shallow, the cove quiet, a little sinister with satiate familiarity, while beyond the darkling horizon the dying storm has raged on. That was the water, we the flotsam. Even after twelve years it is no clearer than that.

It had no beginning and no ending. Out of nothing we howled, unwitting the storm which we had escaped and the foreign strand which we could not escape; that in the interval between two surges of the swell we died who had been too young to have ever lived.

We stopped in the middle of the road to drink again. The land was dark and empty. And quiet: that was what you noticed, remarked. You could hear the earth breathe, like coming out of ether, like it did not yet know, believe, that it was awake. “But now it is peace,” the subadar said. “All men are brothers.”

“You spoke before the Union once,” Bland said. He was blond and tall. When he passed through a room where women were he left a sighing wake like a ferry boat entering the slip. He was a Southerner, too, like Sartoris; but unlike Sartoris, in the five months he had been out, no one had ever found a bullet hole in his machine.

But he had transferred out of an Oxford battalion — he was a Rhodes scholar — with a barnacle and a wound-stripe. When he was tight he would talk about his wife, though we all knew that he was not married.

He took the bottle from Sartoris and drank. “I’ve got the sweetest little wife,” he said. “Let me tell you about her.”

“Dont tell us,” Sartoris said. “Give her to Comyn. He wants a girl.”

“All right,” Bland said. “You can have her, Comyn.”

“Is she blonde?” Comyn said.

“I dont know,” Bland said. He turned back to the subadar. “You spoke before the Union once. I remember you.”

“Ah,” the subadar said. “Oxford. Yes.”

“He can attend their schools among the gentleborn, the bleach-skinned,” Bland said. “But he cannot hold their commission, because gentility is a matter of color and not lineage or behavior.”

“Fighting is more important than truth,” the subadar said. “So we must restrict the prestige and privileges of it to the few so that it will not lose popularity with the many who have to die.”

“Why more important?” I said. “I thought this one was being fought to end war forevermore.”

The subadar made a brief gesture, dark, deprecatory, tranquil. “I was a white man also for that moment. It is more important for the Caucasian because he is only what he can do; it is the sum of him.”

“So you see further than we see?”

“A man sees further looking out of the dark upon the light than a man does in the light and looking out upon the light. That is the principle of the spyglass. The lens is only to tease him with that which the sense that suffers and desires can never affirm.”

“What do you see, then?” Bland said.

“I see girls,” Comyn said. “I see acres and acres of the yellow hair of them like wheat and me among the wheat. Have ye ever watched a hidden dog quartering a wheat field, any of yez?”

“Not hunting bitches,” Bland said.

Comyn turned in the seat, thick and huge. He was big as all outdoors. To watch two mechanics shoehorning him into the cockpit of a Dolphin like two chambermaids putting an emergency bolster into a case too small for it, was a sight to see. “I will beat the head off ye for a shilling,” he said.

“So you believe in the rightness of man?” I said.

“I will beat the heads off yez all for a shilling,” Comyn said.

“I believe in the pitiableness of man,” the subadar said. “That is better.”

“I will give yez a shilling, then,” Comyn said.

“All right,” Sartoris said. “Did you ever try a little whisky for the night air, any of you all?”

Comyn took the bottle and drank. “Acres and acres of them,” he said, “with their little round white woman parts gleaming among the moiling wheat.”

So we drank again, on the lonely road between two beet fields, in the dark quiet, and the turn of the inebriation began to make. It came back from wherever it had gone, rolling down upon us and upon the grave sober rock of the subadar until his voice sounded remote and tranquil and dreamlike, saying that we were brothers.

Monaghan was there then, standing beside our car in the full glare of the headlights of his car, in an R.F.C. cap and an American tunic with both shoulder straps flapping loose, drinking from Comyn’s bottle. Beside him stood a second man, also in a tunic shorter and trimmer than ours, with a bandage about his head.

“I’ll fight you,” Comyn told Monaghan. “I’ll give you the shilling.”

“All right,” Monaghan said. He drank again.

“We are all brothers,” the subadar said. “Sometimes we pause at the wrong inn. We think it is night and we stop, when it is not night. That is all.”

“I’ll give you a sovereign,” Comyn told Monaghan.

“All right,” Monaghan said. He extended the bottle to the other man, the one with the bandaged head.

“I thangk you,” the man said. “I haf plenty yet.”

“I’ll fight him,” Comyn said.

“It is because we can do only within the heart,” the subadar said. “While we see beyond the heart.”

“I’ll be damned if you will,” Monaghan said. “He’s mine.” He turned to the man with the bandaged head. “Aren’t you mine? Here; drink.”

“I haf plenty, I thangk you, gentlemen,” the other said. But I dont think any of us paid much attention to him until we were inside the Cloche-Clos. It was crowded, full of noise and smoke.

When we entered all the noise ceased, like a string cut in two, the end raveling back into a sort of shocked consternation of pivoting faces, and the waiter — an old man in a dirty apron — falling back before us, slack-jawed, with an expression of outraged unbelief, like an atheist confronted with either Christ or the devil.

We crossed the room, the waiter retreating before us, paced by the turning outraged faces, to a table adjacent to one where three French officers sat watching us with that same expression of astonishment and then outrage and then anger.

As one they rose; the whole room, the silence, became staccato with voices, like machine guns. That was when I turned and looked at Monaghan’s companion for the first time, in his green tunic and his black snug breeks and his black boots and his bandage.

He had cut himself recently shaving, and with his bandaged head and his face polite and dazed and bloodless and sick, he looked like Monaghan had been using him pretty hard. Roundfaced, not old, with his immaculately turned bandage which served only to emphasize the generations of difference between him and the turbaned subadar, flanked by Monaghan with his wild face and wild tunic and surrounded by the French people’s shocked and outraged faces, he appeared to contemplate with a polite and alert concern his own struggle against the inebriation which Monaghan was forcing upon him.

There was something Anthony-like about him: rigid, soldierly, with every button in place, with his unblemished bandage and his fresh razor cuts, he appeared to muse furiously upon a clear flame of a certain conviction of individual behavior above a violent and inexplicable chaos.

Then I remarked Monaghan’s second companion: an American military policeman. He was not drinking. He sat beside the German, rolling cigarettes from a cloth sack.

On the German’s other side Monaghan was filling his glass. “I brought him down this morning,” he said. “I’m going to take him home with me.”

“Why?” Bland