Delta Autumn, William Faulkner

Delta Autumn

Soon now they would enter the Delta. The sensation was familiar to him. It had been renewed like this each last week in November for more than fifty years—the last hill, at the foot of which the rich unbroken alluvial flatness began as the sea began at the base of its cliffs, dissolving away beneath the unhurried November rain as the sea itself would dissolve away.

At first they had come in wagons: the guns, the bedding, the dogs, the food, the whisky, the keen heart-lifting anticipation of hunting; the young men who could drive all night and all the following day in the cold rain and pitch a camp in the rain and sleep in the wet blankets and rise at daylight the next morning and hunt.

There had been bear then. A man shot a doe or a fawn as quickly as he did a buck, and in the afternoons they shot wild turkey with pistols to test their stalking skill and marksmanship, feeding all but the breast to the dogs.

But that time was gone now. Now they went in cars, driving faster and faster each year because the roads were better and they had farther and farther to drive, the territory in which game still existed drawing yearly inward as his life was drawing inward, until now he was the last of those who had once made the journey in wagons without feeling it and now those who accompanied him were the sons and even grandsons of the men who had ridden for twenty-four hours in the rain or sleet behind the steaming mules.

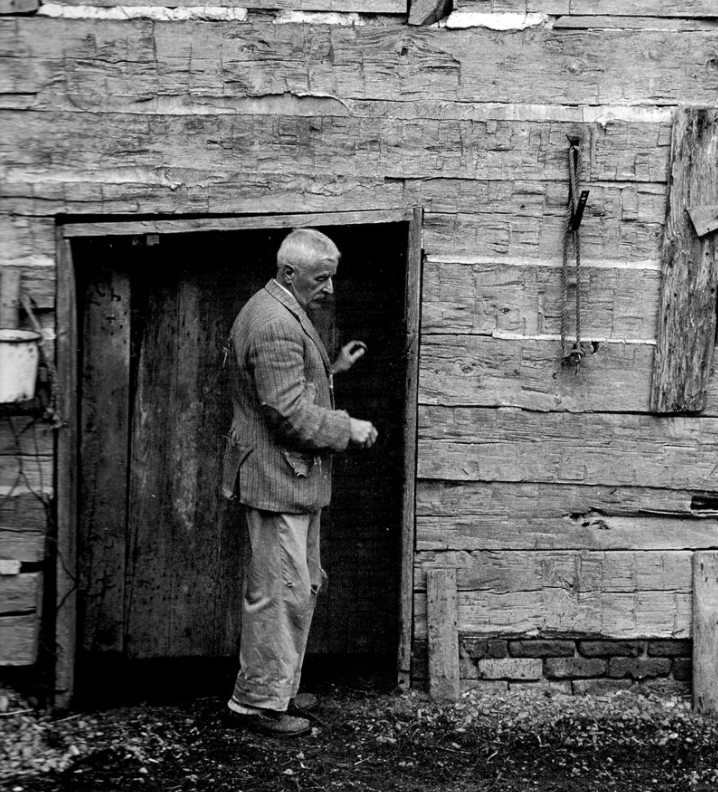

They called him ‘Uncle Ike’ now, and he no longer told anyone how near eighty he actually was because he knew as well as they did that he no longer had any business making such expeditions, even by car.

In fact, each time now, on that first night in camp, lying aching and sleepless in the harsh blankets, his blood only faintly warmed by the single thin whisky-and-water which he allowed himself, he would tell himself that this would be his last.

But he would stand that trip—he still shot almost as well as he ever had, still killed almost as much of the game he saw as he ever killed; he no longer even knew how many deer had fallen before his gun—and the fierce long heat of the next summer would renew him.

Then November would come again, and again in the car with two of the sons of his old companions, whom he had taught not only how to distinguish between the prints left by a buck or a doe but between the sound they made in moving, he would look ahead past the jerking are of the windshield wiper and see the land flatten suddenly and swoop, dissolving away beneath the rain as the sea itself would dissolve, and he would say, “Well, boys, there it is again,”

This time though, he didn’t have time to speak. The driver of the car stopped it, slamming it to a skidding halt on the greasy pavement without warning, actually flinging the two passengers forward until they caught themselves with their braced hands against the dash. “What the hell, Roth!” the man in the middle said. “Can’t you whistle first when you do that? Hurt you, Uncle Ike?”

“No,” the old man said. “What’s the matter?” The driver didn’t answer. Still leaning forward, the old man looked sharply past the face of the man between them, at the face of his kinsman. It was the youngest face of them all, aquiline, saturnine, a little ruthless, the face of his ancestor too, tempered a little, altered a little, staring sombrely through the streaming windshield across which the twin wipers flicked and flicked.

“I didn’t intend to come back in here this time,” he said suddenly and harshly.

“You said that back in Jefferson last week,” the old man said. “Then you changed your mind. Have you changed it again? This aint a very good time to——”

“Oh, Roth’s coming,” the man in the middle said. His name was Legate. He seemed to be speaking to no one, as he was looking at neither of them. “If it was just a buck he was coming all this distance for, now. But he’s got a doe in here.

Of course a old man like Uncle Ike cant be interested in no doe, not one that walks on two legs—when she’s standing up, that is. Pretty light-colored, too. The one he was after them nights last fall when he said he was coon-hunting, Uncle Ike. The one I figured maybe he was still running when he was gone all that month last January. But of course a old man like Uncle Ike aint got no interest in nothing like that.” He chortled, still looking at no one, not completely jeering.

“What?” the old man said. “What’s that?” But he had not even so much as glanced at Legate. He was still watching his kinsman’s face. The eyes behind the spectacles were the blurred eyes of an old man, but they were quite sharp too; eyes which could still see a gun-barrel and what ran beyond it as well as any of them could. He was remembering himself now: how last year, during the final stage by motor boat in to where they camped, a box of food had been lost overboard and how on the next day his kinsman had gone back to the nearest town for supplies and had been gone overnight.

And when he did return, something had happened to him. He would go into the woods with his rifle each dawn when the others went, but the old man, watching him, knew that he was not hunting. “All right,” he said. “Take me and Will on to shelter where we can wait for the truck, and you can go on back.”

“I’m going in,” the other said harshly. “Don’t worry. Because this will be the last of it.”

“The last of deer hunting, or of doe hunting?” Legate said. This time the old man paid no attention to him even by speech. He still watched the young man’s savage and brooding face.

“Why?” he said.

“After Hitler gets through with it? Or Smith or Jones or Roosevelt or Willkie or whatever he will call himself in this country?”

“We’ll stop him in this country,” Legate said. “Even if he calls himself George Washington.”

“How?” Edmonds said. “By singing God bless America in bars at midnight and wearing dime-store flags in our lapels?”

“So that’s what’s worrying you,” the old man said. “I aint noticed this country being short of defenders yet, when it needed them. You did some of it yourself twenty-odd years ago, before you were a grown man even. This country is a little mite stronger than any one man or group of men, outside of it or even inside of it either.

I reckon, when the time comes and some of you have done got tired of hollering we are whipped if we dont go to war and some more are hollering we are whipped if we do, it will cope with one Austrian paper-hanger, no matter what he will be calling himself.

My pappy and some other better men than any of them you named tried once to tear it in two with a war, and they failed.”

“And what have you got left?” the other said. “Half the people without jobs and half the factories closed by strikes. Half the people on public dole that wont work and half that couldn’t work even if they would. Too much cotton and corn and hogs, and not enough for people to eat and wear. The country full of people to tell a man how he cant raise his own cotton whether he will or wont, and Sally Rand with a sergeant’s stripe and not even the fan couldn’t fill the army rolls. Too much not-butter and not even the guns——”

“We got a deer camp—if we ever get to it,” Legate said. “Not to mention does.”

“It’s a good time to mention does,” the old man said. “Does and fawns both. The only fighting anywhere that ever had anything of God’s blessing on it has been when men fought to protect does and fawns. If it’s going to come to fighting, that’s a good thing to mention and remember too.”

“Haven’t you discovered in—how many years more than seventy is it?—that women and children are one thing there’s never any scarcity of?” Edmonds said.

“Maybe that’s why all I am worrying about right now is that ten miles of river we still have got to run before fore we can make camp,” the old man said. “So let’s get on.”

They went on. Soon they were going fast again, as Edmonds always drove, consulting neither of them about the speed just as he had given neither of them any warning when he slammed the car to stop. The old man relaxed again. He watched, as he did each recurrent November while more than sixty of them passed, the land which he had seen change.

At first there had been only the old towns along the River and the old towns along the hills, from each of which the planters with their gangs of slaves and then of hired laborers had wrested from the impenetrable jungle of water-standing cane and cypress, gum and holly and oak and ash, cotton patches which as the years passed became fields and then plantations.

The paths made by deer and bear became roads and then highways, with towns in turn springing up along them