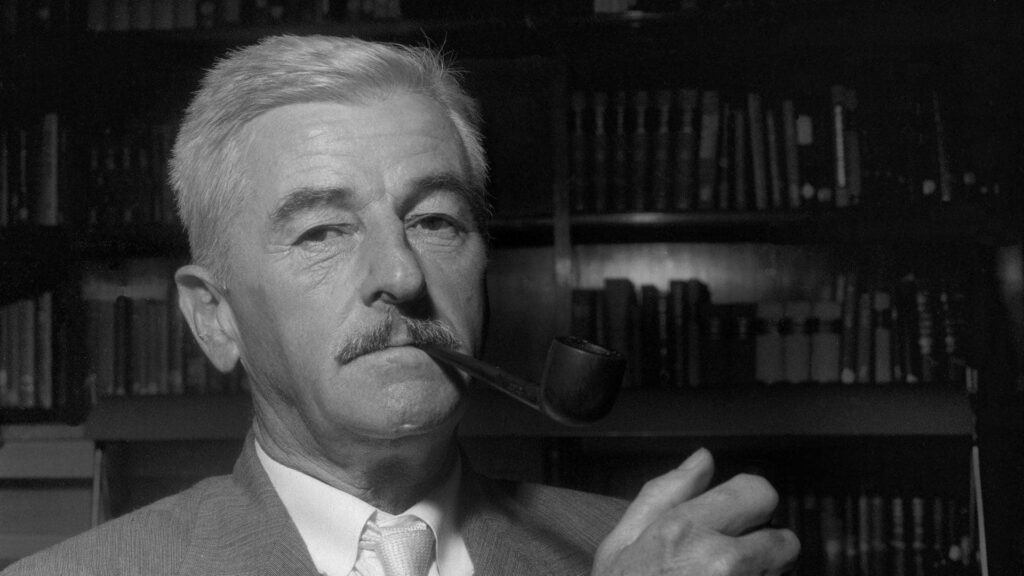

The Courthouse, A Name for the City (Requiem for a Nun) William Faulkner

THE COURTHOUSE IS less old than the town, which began somewhere under the turn of the century as a Chickasaw Agency trading-post and so continued for almost thirty years before it discovered, not that it lacked a depository for its records and certainly not that it needed one, but that only by creating or anyway decreeing one, could it cope with a situation which otherwise was going to cost somebody money;

The settlement had the records; even the simple dispossession of Indians begot in time a minuscule of archive, let alone the normal litter of man’s ramshackle confederation against environment — that time and that wilderness — in this case, a meagre, fading, dog-eared, uncorrelated, at times illiterate sheaf of land grants and patents and transfers and deeds, and tax- and militia-rolls, and bills of sale for slaves, and counting-house lists of spurious currency and exchange rates, and liens and mortgages, and listed rewards for escaped or stolen Negroes and other livestock, and diary-like annotations of births and marriages and deaths and public hangings and land-auctions, accumulating slowly for those three decades in a sort of iron pirate’s chest in the back room of the post-office-trading-post-store, until that day thirty years later when, because of a jailbreak compounded by an ancient monster iron padlock transported a thousand miles by horseback from Carolina, the box was removed to a small new lean-to room like a wood- or tool-shed built two days ago against one outside wall of the morticed-log mud-chinked shake-down jail; and thus was born the Yoknapatawpha County courthouse: by simple fortuity, not only less old than even the jail, but come into existence at all by chance and accident: the box containing the documents not moved from any place, but simply to one; removed from the trading-post back room not for any reason inherent in either the back room or the box, but on the contrary: which — the box — was not only in nobody’s way in the back room, it was even missed when gone since it had served as another seat or stool among the powder- and whiskey-kegs and firkins of salt and lard about the stove on winter nights; and was moved at all for the simple reason that suddenly the settlement (overnight it would become a town without having been a village; one day in about a hundred years it would wake frantically from its communal slumber into a rash of Rotary and Lion Clubs and Chambers of Commerce and City Beautifuls: a furious beating of hollow drums toward nowhere, but merely to sound louder than the next little human clotting to its north or south or east or west, dubbing itself city as Napoleon dubbed himself emperor and defending the expedient by padding its census rolls — a fever, a delirium in which it would confound forever seething with motion and motion with progress.

But that was a hundred years away yet; now it was frontier, the men and women pioneers, tough, simple, and durable, seeking money or adventure or freedom or simple escape, and not too particular how they did it.) discovered itself faced not so much with a problem which had to be solved, as a Damocles sword of dilemma from which it had to save itself;

Even the jailbreak was fortuity: a gang — three or four — of Natchez Trace bandits (twenty-five years later legend would begin to affirm, and a hundred years later would still be at it, that two of the bandits were the Harpes themselves, Big Harpe anyway, since the circumstances, the method of the breakout left behind like a smell, an odour, a kind of gargantuan and bizarre playfulness at once humorous and terrifying, as if the settlement had fallen, blundered, into the notice or range of an idle and whimsical giant.

Which — that they were the Harpes — was impossible, since the Harpes and even the last of Mason’s ruffians were dead or scattered by this time, and the robbers would have had to belong to John Murrel’s organisation — if they needed to belong to any at all other than the simple fraternity of rapine.) captured by chance by an incidental band of civilian more-or-less militia and brought in to the Jefferson jail because it was the nearest one, the militia band being part of a general muster at Jefferson two days before for a Fourth-of-July barbecue, which by the second day had been refined by hardy elimination into one drunken brawling which rendered even the hardiest survivors vulnerable enough to be ejected from the settlement by the civilian residents, the band which was to make the capture having been carried, still comatose, in one of the evicting wagons to a swamp four miles from Jefferson known as Hurricane Bottoms, where they made camp to regain their strength or at least their legs, and where that night the four — or three — bandits, on the way across country to their hide-out from their last exploit on the Trace, stumbled onto the campfire.

And here report divided; some said that the sergeant in command of the militia recognised one of the bandits as a deserter from his corps, others said that one of the bandits recognised in the sergeant a former follower of his, the bandit’s, trade.

Anyway, on the fourth morning all of them, captors and prisoners, returned to Jefferson in a group, some said in confederation now seeking more drink, others said that the captors brought their prizes back to the settlement in revenge for having been evicted from it. Because these were frontier, pioneer times, when personal liberty and freedom were almost a physical condition like fire or flood, and no community was going to interfere with anyone’s morals as long as the amoralist practised somewhere else, and so Jefferson, being neither on the Trace nor the River but lying about midway between, naturally wanted no part of the underworld of either;

But they had some of it now, taken as it were by surprise, unawares, without warning to prepare and fend off. They put the bandits into the log-and-mud-chinking jail, which until now had had no lock at all since its clients so far had been amateurs — local brawlers and drunkards and runaway slaves — for whom a single heavy wooden beam in slots across the outside of the door like on a corncrib, had sufficed. But they had now what might be four — three — Dillingers or Jesse Jameses of the time, with rewards on their heads.

So they locked the jail; they bored an auger hole through the door and another through the jamb and passed a length of heavy chain through the holes and sent a messenger on the run across to the post-office-store to fetch the ancient Carolina lock from the last Nashville mail-pouch — the iron monster weighing almost fifteen pounds, with a key almost as long as a bayonet, not just the only lock in that part of the country, but the oldest lock in that cranny of the United States, brought there by one of the three men who were what was to be Yoknapatawpha County’s coeval pioneers and settlers, leaving in it the three oldest names — Alexander Holston, who came as half groom and half bodyguard to Doctor Samuel Habersham, and half nurse and half tutor to the doctor’s eight-year-old motherless son, the three of them riding horseback across Tennessee from the Cumberland Gap along with Louis Grenier, the Huguenot younger son who brought the first slaves into the country and was granted the first big land patent and so became the first cotton planter; while Doctor Habersham, with his worn black bag of pills and knives and his brawny taciturn bodyguard and his half orphan child, became the settlement itself (for a time, before it was named, the settlement was known as Doctor Habersham’s, then Habersham’s, then simply Habersham; a hundred years later, during a schism between two ladies’ clubs over the naming of the streets in order to get free mail delivery, a movement was started, first, to change the name back to Habersham; then, failing that, to divide the town in two and call one half of it Habersham after the old pioneer doctor and founder) — friend of old Issetibbeha, the Chickasaw chief (the motherless Habersham boy, now a man of twenty-five, married one of Issetibbeha’s granddaughters and in the thirties emigrated to Oklahoma with his wife’s dispossessed people), first unofficial, then official Chickasaw agent until he resigned in a letter of furious denunciation addressed to the President of the United States himself; and — his charge and pupil a man now — Alexander Holston became the settlement’s first publican, establishing the tavern still known as the Holston House, the original log walls and puncheon floors and hand-morticed joints of which are still buried somewhere beneath the modern pressed glass and brick veneer and neon tubes. The lock was his;

Fifteen pounds of useless iron lugged a thousand miles through a desert of precipice and swamp, of flood and drouth and wild beasts and wild Indians and wilder white men, displacing that fifteen pounds better given to food or seed to plant food or even powder to defend with, to become a fixture, a kind of landmark, in the bar of a wilderness ordinary, locking and securing nothing, because there was nothing behind the heavy bars and shutters needing further locking and securing; not even a paper weight because the only papers in the