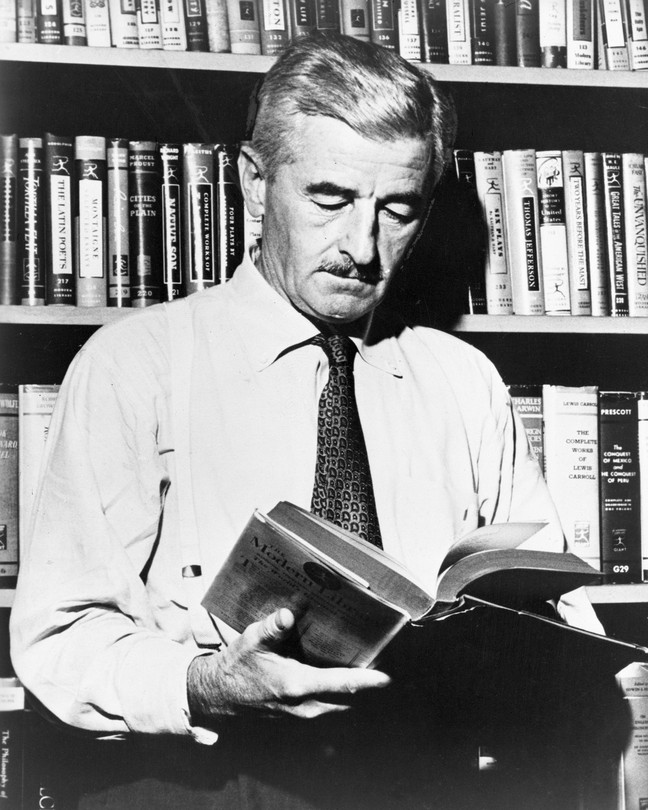

The Tall Men, William Faulkner

The Tall Men

THEY PASSED THE dark bulk of the cotton gin. Then they saw the lamplit house and the other car, the doctor’s coupé, just stopping at the gate, and they could hear the hound baying.

“Here we are,” the old deputy marshal said.

“What’s that other car?” the younger man said, the stranger, the state draft investigator.

“Doctor Schofield’s,” the marshal said. “Lee McCallum asked me to send him out when I telephoned we were coming.”

“You mean you warned them?” the investigator said. “You telephoned ahead that I was coming out with a warrant for these two evaders? Is this how you carry out the orders of the United States Government?”

The marshal was a lean, clean old man who chewed tobacco, who had been born and lived in the county all his life.

“I understood all you wanted was to arrest these two McCallum boys and bring them back to town,” he said.

“It was!” the investigator said. “And now you have warned them, given them a chance to run. Possibly put the Government to the expense of hunting them down with troops. Have you forgotten that you are under a bond yourself?”

“I ain’t forgot it,” the marshal said. “And ever since we left Jefferson I been trying to tell you something for you not to forget. But I reckon it will take these McCallums to impress that on you. . . . Pull in behind the other car. We’ll try to find out first just how sick whoever it is that is sick is.”

The investigator drew up behind the other car and switched off and blacked out his lights. “These people,” he said. Then he thought, But this doddering, tobacco-chewing old man is one of them, too, despite the honor and pride of his office, which should have made him different.

So he didn’t speak it aloud, removing the keys and getting out of the car, and then locking the car itself, rolling the windows up first, thinking, These people who lie about and conceal the ownership of land and property in order to hold relief jobs which they have no intention of performing, standing on their constitutional rights against having to work, who jeopardize the very job itself through petty and transparent subterfuge to acquire a free mattress which they intend to attempt to sell; who would relinquish even the job, if by so doing they could receive free food and a place, any rathole, in town to sleep in; who, as farmers, make false statements to get seed loans which they will later misuse, and then react in loud vituperative outrage and astonishment when caught at it.

And then, when at long last a suffering and threatened Government asks one thing of them in return, one thing simply, which is to put their names down on a selective-service list, they refuse to do it.

The old marshal had gone on. The investigator followed, through a stout paintless gate in a picket fence, up a broad brick walk between two rows of old shabby cedars, toward the rambling and likewise paintless sprawl of the two-story house in the open hall of which the soft lamplight glowed and the lower story of which, as the investigator now perceived, was of logs.

He saw a hall full of soft lamplight beyond a stout paintless gallery running across the log front, from beneath which the same dog which they had heard, a big hound, came booming again, to stand foursquare facing them in the walk, bellowing, until a man’s voice spoke to it from the house. He followed the marshal up the steps onto the gallery.

Then he saw the man standing in the door, waiting for them to approach — a man of about forty-five, not tall, but blocky, with a brown, still face and horseman’s hands, who looked at him once, brief and hard, and then no more, speaking to the marshal, “Howdy, Mr. Gombault. Come in.”

“Howdy, Rafe,” the marshal said. “Who’s sick?”

“Buddy,” the other said. “Slipped and caught his leg in the hammer mill this afternoon.”

“Is it bad?” the marshal said.

“It looks bad to me,” the other said. “That’s why we sent for the doctor instead of bringing him in to town. We couldn’t get the bleeding stopped.”

“I’m sorry to hear that,” the marshal said. “This is Mr. Pearson.” Once more the investigator found the other looking at him, the brown eyes still, courteous enough in the brown face, the hand he offered hard enough, but the clasp quite limp, quite cold. The marshal was still speaking. “From Jackson. From the draft board.” Then he said, and the investigator could discern no change whatever in his tone: “He’s got a warrant for the boys.”

The investigator could discern no change whatever anywhere. The limp hard hand merely withdrew from his, the still face now looking at the marshal. “You mean we have declared war?”

“No,” the marshal said.

“That’s not the question, Mr. McCallum,” the investigator said. “All required of them was to register. Their numbers might not even be drawn this time; under the law of averages, they probably would not be. But they refused — failed, anyway — to register.”

“I see,” the other said. He was not looking at the investigator. The investigator couldn’t tell certainly if he was even looking at the marshal, although he spoke to him, “You want to see Buddy? The doctor’s with him now.”

“Wait,” the investigator said. “I’m sorry about your brother’s accident, but I—” The marshal glanced back at him for a moment, his shaggy gray brows beetling, with something at once courteous yet a little impatient about the glance, so that during the instant the investigator sensed from the old marshal the same quality which had been in the other’s brief look.

The investigator was a man of better than average intelligence; he was already becoming aware of something a little different here from what he had expected. But he had been in relief work in the state several years, dealing almost exclusively with country people, so he still believed he knew them. So he looked at the old marshal, thinking, Yes.

The same sort of people, despite the office, the authority and responsibility which should have changed him. Thinking again, These people. These people. “I intend to take the night train back to Jackson,” he said. “My reservation is already made. Serve the warrant and we will—”

“Come along,” the old marshal said. “We are going to have plenty of time.”

So he followed — there was nothing else to do — fuming and seething, attempting in the short length of the hall to regain control of himself in order to control the situation, because he realized now that if the situation were controlled, it would devolve upon him to control it; that if their departure with their prisoners were expedited, it must be himself and not the old marshal who would expedite it. He had been right.

The doddering old officer was not only at bottom one of these people, he had apparently been corrupted anew to his old, inherent, shiftless sloth and unreliability merely by entering the house. So he followed in turn, down the hall and into a bedroom; whereupon he looked about him not only with amazement but with something very like terror.

The room was a big room, with a bare unpainted floor, and besides the bed, it contained only a chair or two and one other piece of old-fashioned furniture.

Yet to the investigator it seemed so filled with tremendous men cast in the same mold as the man who had met them that the very walls themselves must bulge. Yet they were not big, not tall, and it was not vitality, exuberance, because they made no sound, merely looking quietly at him where he stood in the door, with faces bearing an almost identical stamp of kinship — a thin, almost frail old man of about seventy, slightly taller than the others; a second one, white-haired, too, but otherwise identical with the man who had met them at the door; a third one about the same age as the man who had met them, but with something delicate in his face and something tragic and dark and wild in the same dark eyes; the two absolutely identical blue-eyed youths; and lastly the blue-eyed man on the bed over which the doctor, who might have been any city doctor, in his neat city suit, leaned — all of them turning to look quietly at him and the marshal as they entered.

And he saw, past the doctor, the slit trousers of the man on the bed and the exposed, bloody, mangled leg, and he turned sick, stopping just inside the door under that quiet, steady regard while the marshal went up to the man who lay on the bed, smoking a cob pipe, a big, old-fashioned, wicker-covered demijohn, such as the investigator’s grandfather had kept his whisky in, on the table beside him.

“Well, Buddy,” the marshal said, “this is bad.”

“Ah, it was my own damn fault,” the man on the bed said. “Stuart kept warning me about that frame I was using.”

“That’s correct,” the second old one said.

Still the others said nothing. They just looked steadily and quietly at the investigator until the marshal turned slightly and said, “This is Mr. Pearson. From Jackson. He’s got a warrant for the boys.”

Then the man on the bed said, “What for?”

“That draft business, Buddy,” the marshal said.

“We’re not at war now,” the man on the bed said.

“No,” the marshal said. “It’s that new law. They didn’t register.”

“What are you going to do