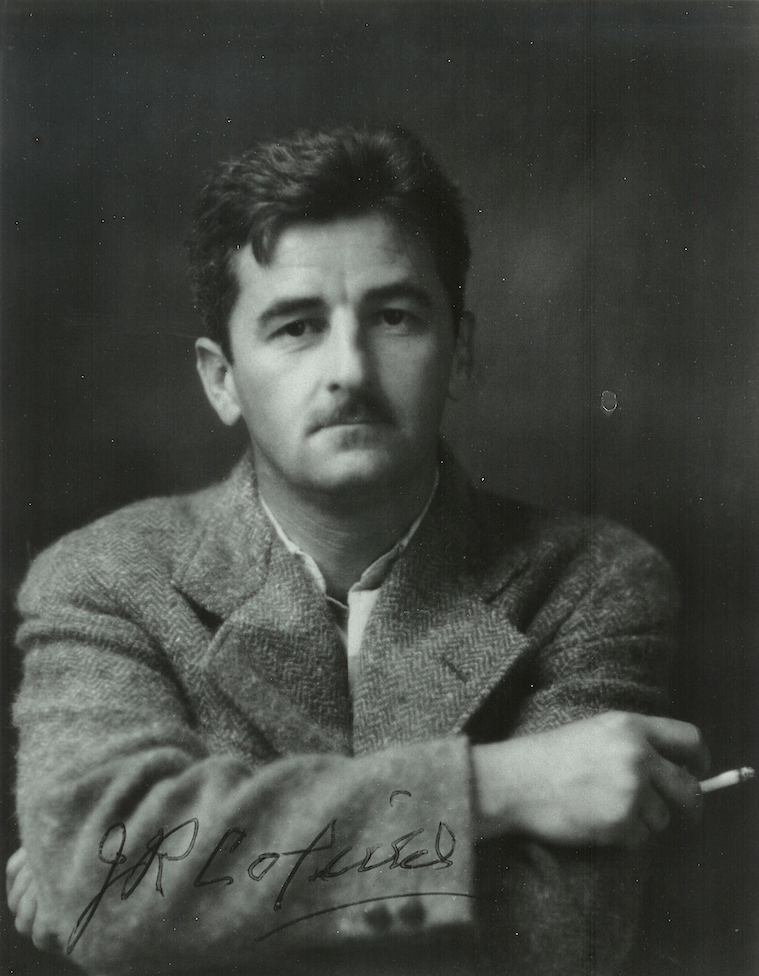

Two Dollar Wife, William Faulkner

Two Dollar Wife

College Life, Volume XVIII, 1936

“AIN’T SHE NEVER going to be ready!” Maxwell Johns stared at himself in the mirror. He watched himself light a cigarette and snap the match backward over his shoulder. It struck the hearth and bounced, still burning, toward the rug.

“What the hell do I care if it burns the damn dump down!” he snarled, striding up and down the garish parlor of the Houston home. He stared at his reflection again — slim young body in evening clothes, smooth dark hair, smooth white face. He could hear, in the room overhead, Doris Houston and her mother shrieking at each other.

“Listen at ’em squall!” he grunted. “You’d think it was a knock-down-and-drag-out going on instead of a flounce getting into her duds. Oh, hell! Their brains are fuzzy as the cotton we grow!”

A colored maid entered the room and puttered about a moment, her vast backside billowing like a high wave under oil. She glanced at Maxwell and sniffed her way out of the room.

The screams above reached a crescendo. Then he heard rushing feet, eager and swift — a bright eager clatter, young and evanescent.

A final screech from above seemed to shoot Doris Houston into the room like a pip squeezed from an orange. She was thin as a dragonfly, honey-haired, with long coltish legs. Her small face was alternate patches of dead white and savage red.

She carried a fur coat over her arm and held onto one shoulder of her dress with the other hand. The other shoulder, with a dangling strap, had slipped far down.

Doris shrugged the gown back into place and mumbled between her red lips. A needle glinted between her white teeth, the gossamer thread floating out as she flung the coat down and whirled her back to Maxwell. “Here, Unconscious, sew me up!” he interpreted her mumbled words.

“Good God, I just sewed you into it night before last!” Maxwell growled. “And I sewed you into it Christmas Eve, and I sewed—”

“Aw, dry up!” said Doris. “You did your share of tearing it off of me! Sew it good this time, and let it stay sewed!”

He sewed it, muttering to himself, with long, savage stitches like a boy sewing the ripped cover of a baseball. He snapped the thread, juggled the needle from one hand to the other for a moment and then thrust it carelessly into the seat cover of a chair.

Doris shrugged the strap into place with a wriggle and reached for her coat. Outside a motor horn brayed, “Here they are!” she snapped. “Come on!”

Again feet sounded on the stairs — like lumps of half-baked dough slopping off a table. Mrs. Houston thrust her frizzled hair and her diamonds into the room.

“Doris!” she shrieked. “Where are you going tonight? Maxwell, don’t you dare let Doris stay out till all hours again like she did Christmas Eve! I don’t care if it is New Year’s! Do you hear? Doris, you come home—”

“All right! All right!” squawked Doris without looking back. “Come on, Unconscious!”

“Get in!” barked Walter Mitchell, driver of the car. “Get in back, Doris, damn it! Lucille, get your legs outa my lap! How the hell you expect me to drive?”

As the car ripped through the outer fringe of the town, a second car, also containing two couples, turned in from a side road. The drivers blatted horns at each other in salute. Side by side they swerved into the straight road that led past the Country Club. They raced, roaring, rocking — sixty — seventy — seventy-five, hub brushing hub, outer wheels on the rims of the road. Behind the steering wheels glowered two almost identical faces — barbered, young, grim.

Far ahead gleamed the white gates of the Country Club. “You better slow down!” shrieked Doris.

“Slow down, hell!” growled Mitchell, foot and accelerator both flat on the floorboards.

The other car drew ahead, horn blatting derisively, voices squalling meaningless gibberish. Mitchell swore under his breath.

Scre-e-e-e-each!

The lead car took the turn on two wheels, leaped, bucked, careened wildly and shot up the drive. Mitchell slammed his throttle shut and drifted on down the dark road. A mile from the Country Club he ground the car to a stop, switched off engine and lights and pulled a flask from his pocket.

“Let’s have a drink!” he grunted, proffering the flask.

“I don’t want to stop here,” Doris said. “I want to go to the Club.”

“Don’t you want a drink?” asked Mitchell.

“No. I don’t want a drink, either. I want to go to the Club.”

“Don’t pay any attention to her,” said Maxwell. “If anybody comes along I’ll show ’em the license.”

A month before, just after Maxwell had been suspended from Sewanee, Mitchell had dared Doris and him to get married. Maxwell had borrowed two dollars from the Negro janitor at the Cotton Exchange, where Max “worked” in his father’s office, and they had driven a hundred miles and bought a license. Then Doris changed her mind. Maxwell still carried the license in his pocket, now a little smeary from moisture and friction.

Lucille shrieked with laughter.

“Max, you behave yourself!” squawked Doris. “Take your hands away!”

“Here, give me the license,” said Walter, “I’ll tie it on the radiator. Then they won’t even have to get out of the car to look at it.”

“No you won’t!” Doris cried.

“What you got to say about it?” demanded Walter. “Max was the one that paid two dollars for it — not you.”

“I don’t care! It’s got my name on it!”

“Gimme my two dollars back and you can have it,” said Maxwell.

“I haven’t got two dollars. You take me back to the Club, Walter Mitchell!”

“I’ll give you two bucks for it, Max,” said Walter.

“Okay,” agreed Maxwell, putting his hand to his coat. Doris flung herself at him.

“No you don’t!” she cried. “I’m going to tell daddy on you!”

“What do you care?” protested Walter. “I’m going to scratch out yours and Max’s names and put mine and Lucille’s in. We’re liable to need it!”

“I don’t care! Mine will still be on it and it will be bigamy.”

“You mean incest, honey,” Lucille said.

“I don’t care what I mean. I’m going back to the Club!”

“Are you?” Walter said. “Tell them we’ll be there after while.” He handed Maxwell the flask.

Doris banged the door open and jumped out.

“Hey, wait!” Walter cried. “I didn’t—”

Already they could hear Doris’ spike heels hitting the road hard. Walter turned the car.

“You better get out and walk behind her,” he told Maxwell. “You left home with her. Get her to the Club, anyway. It ain’t far — not even a mile, hardly.”

“Watch where you’re going!” yelped Maxwell. “Here comes a car behind us!”

Walter drew aside and flashed his spot on the other car as it passed.

“It’s Hap White!” shrieked Lucille, craning her neck. “He’s got that Princeton man, Jornstadt, with him — the handsome one all the girls are crazy about. He’s from Minnesota and is visiting his aunt in town.”

The other car ground to a halt beside Doris. The door opened. She got in.

“The little snake!” shrilled Lucille. “I bet she knew Jornstadt was in that car. I bet she made a date with Hap White to pick her up.”

Walter Mitchell chuckled maliciously. “ ‘There goes my girl—’ “ he hummed.

Maxwell swore savagely under his breath.

There were already five in the other car. Doris sat on Jornstadt’s lap. He could feel the warmth and the rounded softness of her legs. He held her steady drawing her back against him. Doris wriggled slightly and his arm tightened.

Jornstadt drew a deep breath freighted with the perfume of the honey-colored hair. His arm tightened still more.

A moment later Mitchell’s car roared past.

Lurking between two parked cars, Walter and Maxwell watched the six from Hap White’s car enter the club house. The group [passed] the girls in a bee-like clot around the tall Princeton man, whose beautifully ridged head towered over them. The blaring music seemed to be a triumphant carpet spread for him, derisive and salutant.

Walter handed his almost empty flask to Maxwell. Max tilted it up.

“I know a good place for that Princeton guy,” he said, wiping his lips.

“Huh?”

“The morgue,” said Max.

“Gonna dance?” asked Walter.

“Hell, no! Let’s go to the cloak room. Oughta be a crap game in there.”

There was. Above the kneeling ring of tense heads and shoulders, they saw the Princeton man, Jornstadt, and Hap White, a fat youth with a cherubic face and a fawning manner. They were drinking, turn about, from a thick tumbler in which a darky poured corn from a Coca-Cola bottle. Hap waved a greeting. “Hi-yi, boy,” he addressed Max. “Little family trouble?”

“Nope,” said Maxwell evenly. “Gimme a drink.”

Max and Walter watched the crap game. Hap and Jornstadt strolled out, the music squalling briefly through the opening and closing door. Around the kneeling ring droned monotonous voices.

“E-eleven! Shoot four bits.”

“You’re faded! Snake eyes! Let the eight bits ride?”

“C’mon, Little Joe!”

“Ninety days in the calaboose! Let it ride!”

The bottle went around. The door began banging open and shut. The cloak room became crowded, murky with cigarette smoke. The music had stopped.

Suddenly pandemonium broke loose: the rising wail of a fire siren, the shrieks of whistles from the cotton gins scattered about the countryside, the crack of pistols and rifles and the duller boom of shotguns. On the veranda girls shrieked and giggled.

“Happy New Year!” said Walter viciously. Max glared at him, shucked off his coat and ripped his collar open.

“Lemme in that game!” he snarled.

A tall man with beautifully ridged hair had just sauntered past the open door. On his arm