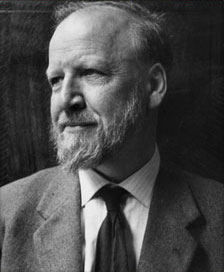

Sir William Gerald Golding CBE FRSL (19 September 1911 – 19 June 1993) was a British novelist, playwright, and poet. Best known for his debut novel Lord of the Flies (1954), he published another twelve volumes of fiction in his lifetime. In 1980, he was awarded the Booker Prize for Rites of Passage, the first novel in what became his sea trilogy, To the Ends of the Earth. He was awarded the 1983 Nobel Prize in Literature.

As a result of his contributions to literature, Golding was knighted in 1988. He was a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. In 2008, The Times ranked Golding third on its list of “The 50 greatest British writers since 1945”.

William Gerald Golding was born on September 19, 1911 in the village of St. Columb Minor (Cornwall) in the family of Alec Golding, a school teacher and author of several textbooks. William retained few memories of his preschool childhood: he had no acquaintances or friends, his social circle was limited to family members and his nanny Lily. All that was remembered were walks through the countryside, long trips to the Cornish sea coast, and fascination with “the horrors and darkness of the family mansion in Marlborough and the nearby cemetery.” During these early years, Golding developed two passions: reading and mathematics. The boy began his self-education with the classics (The Odyssey, Homer), read the novels of J. Swift, E.R. Burroughs, Jules Verne, E.A. Poe. In 1921, William entered Marlborough Grammar School, where his father Alec taught science. Here the teenager first had the idea of writing: at the age of twelve, he conceived his first work of fiction, dedicated to the theme of the origins of the trade union movement. Only the first sentence of the planned 12-volume epic survives: “I was born in the Duchy of Cornwall on October 11, 1792; my parents were rich but honest people.” As noted later, the use of “but” already spoke volumes.

In 1930, with a particular focus on Latin, William Golding entered Brasenose College at the University of Oxford, where, following the wishes of his parents, he decided to study the natural sciences. It took him two years to understand the error of his choice and in 1932, changing the curriculum, he concentrated on studying English language and literature. At the same time, Golding not only retained, but also developed an interest in antiquity; in particular to the history of primitive communities. It was this interest (according to the critic B. Oldsey) that determined the ideological basis of his first serious works. In June 1934 he graduated from college with a second degree diploma.

Literary debut

While a student at Oxford, Golding began writing poetry; At first, this hobby served as a kind of psychological counterweight to the need to immerse myself in the exact sciences. As Bernard F. Dick wrote, the aspiring writer began simply to “write down his observations—about nature, unrequited love, the call of the seas, and the temptations of rationalism.” One of his student friends independently compiled these excerpts into a collection and sent them to Macmillan, which was preparing a special series of publications of poetry by young authors. One morning in the autumn of 1934, Golding unexpectedly received a check for five pounds sterling for the collection Poems by W. G. Golding, thus learning about the beginning of his literary career.

Subsequently, Golding repeatedly expressed regret that this collection was published; once he even purchased a used copy – solely to tear it up and throw it away (only later did he find out that he had destroyed a collectible rarity). However, the poems of the 23-year-old poet subsequently began to be considered by critics as quite “mature and original”; in addition, it was noted that they clearly characterize the range of interests of the author, the central place in which is occupied by the theme of the division of society and criticism of rationalism. Among the poems that scholars subsequently paid attention to were “Non-Philosopher’s Song,” a sonnet about the conflict of “mind and heart,” and the anti-rationalist work “Mr. Pope.” In 1935 the collection sold for a shilling per copy; subsequently, when its author became famous, the cost of the rare book jumped to several thousand dollars.

Golding received his BA in 1935 and began teaching at Michael Hall School in Streatham, south London, in the autumn. During these years, while working part-time in a clearing house and social services (in particular, in a London homeless shelter), he began writing plays, which he himself staged in a small London theater. In the autumn of 1938, Golding returned to Oxford for his graduate degree; in January of the following year he began preparatory teaching practice at Salisbury’s Bishop Wordsworth School, initially at Maidstone Grammar School, where he met Anne Brookfield, a specialist in analytical chemistry. In September 1939, they got married and moved to Salisbury: here the aspiring writer began teaching English and philosophy – directly at the Wordsworth School. In December of the same year, shortly after the birth of his first child, Golding left to serve in the navy.

War: 1941-1945

Golding’s first warship was HMS Galatea, which operated in the North Atlantic Ocean. In early 1942, Golding was transferred to Liverpool, where, as part of the maritime patrol unit, he carried out long hours of duty at Gladstone Dock. In the spring of 1942 he was posted to MD1, a military research center in Buckinghamshire, and in early 1943, in accordance with a petition, he was returned to the active fleet. Golding soon found himself in New York, where he began organizing the transportation of destroyers from the manufacturer’s docks in New Jersey to Great Britain. Having undergone special training on a missile-carrying landing ship, as the commander of such a ship, he took part in the events of D Day: the Allied landing in Normandy and the invasion of Walcheren Island.

The life experience of the war years, as the writer himself admitted later, deprived him of any illusions regarding the properties of human nature. “I began to understand what people are capable of. “Anyone who went through the war and did not understand that people create evil, just as a bee produces honey, is either blind or out of his mind,” he said. “As a young man, before the war, I had lightweight, naive ideas about man. But I went through the war, and it changed me. The war taught me—and many others—something completely different,” the writer said in an interview with Douglas A. Davis of the New Republic.

World famous

Demobilized in September 1945, William Golding returned to teaching at Wordsworth School in Salisbury; During these same days he began a serious study of ancient Greek literature. “If I really had to choose literary adoptive parents, I would name such big names as Euripides, Sophocles, perhaps Herodotus… I can also note that I developed a deep love for Homer,” said writer to J. Baker (“William Golding, A Critical Study”). At the same time, Golding returned to his pre-war hobby: literary activity; at first – to writing reviews and articles for magazines. None of the writer’s four early novels were published; all manuscripts were subsequently lost. Golding later said that these attempts were doomed to failure, because in them he was trying to satisfy needs – not his own, but the publishing ones. From a writer who went through the war, they expected something based on war experience – a memoir or a novel.

In 1952, Golding began work on a novel entitled Strangers from Within; in January of the following year, he began sending manuscripts to publishers, receiving refusals over and over again. In 1953, the novel was read and rejected by publishers for seven months; the Faber & Faber reviewer found the work “absurd, uninteresting, empty and boring.” A total of twenty-one publishers returned the manuscript to the author. And then Charles Monteith, a former lawyer hired by the publishing house as editor a month earlier, almost literally took the novel out of the trash can. He persuaded Faber & Faber to buy the work – for the ridiculous sum of 60 pounds sterling.

An allegorical novel about a group of schoolchildren stranded on an island during some kind of war (most likely unfolding in the near future), heavily edited by Monteith and under the new title Lord of the Flies, it was published in September 1954 . Originally conceived as an ironic “commentary” to R. M. Ballantyne’s “Coral Island,” it was a complex allegory of original sin combined with reflections on the deepest human essence. The first responses to this work, adventure in plot, apocalyptic in spirit, were restrained and ambiguous. After its paperback release, the book became a bestseller in the UK; As the novel’s reputation grew, the attitude of literary criticism towards it also changed. Ultimately, “Lord of the Flies” in terms of the level of interest on the part of analysts turned out to be comparable to the two main books of George Orwell. In 1955 Golding was elected to the Royal Society of Literature. The writer gained popularity in the USA after the next re-release of Lord of the Flies in 1959.

Throughout his life, Golding considered his most famous novel “boring and damp” and its language as “schoolboy” (English: O-level stuff). He didn’t take the fact that Lord of the Flies was considered a modern classic too seriously, and he considered the money he made from it to be the equivalent of “winning Monopoly.” The writer sincerely did not understand how this novel could leave his stronger books in the shadow: “The Heirs,” “The Spire” and “Martin the Thief.” At the end of his life, Golding could not bring himself to even re-read the manuscript in its original, unedited version, fearing that he would become so upset “that he might do something terrible to himself.” Meanwhile, in his diary, Golding revealed the deeper reasons for his disgust with Lord of the Flies: “Basically, I despise myself, and it is important to me that I am not discovered, exposed, recognized, disturbed” (English …basically I despise myself and am anxious not to be discovered, uncovered, detected, rumbled).

1955—1963

Golding continued to teach until 1960: all this time he wrote in his free hours. His second novel, The Inheritors, was published in 1955; the theme “social vice as a consequence of the original depravity of human nature” received a new development here. The novel, which takes place at the dawn of humanity, was later called by Golding his favorite; The work was also highly appreciated by literary critics, who paid attention to how the author developed the ideas of “Lord of the Flies” here.

In 1956, the novel Pincher Martin was published; one of the writer’s most complex works in the United States was published under the title “The Two Deaths of Christopher Martin”: the publishers feared that the slang meaning of the word “pinscher” (“petty thief”) might be unknown to the reader here. The story of the “modern Faust”, who “refuses to accept death even from the hands of God” – a shipwrecked naval officer who climbs onto a cliff, which seems to him to be an island and vainly clings to life – completed the “primitive” stage in Golding’s work only formally; The exploration of the main themes of the first two novels is continued here in a new way, with an experimental structure and sophisticated attention to the smallest details.

In the second half of the 1950s, Golding began to take an active part in the capital’s literary life, collaborate as a reviewer with such publications as The Bookman and The Listener, and appear on the radio. That same year, his short story Envoy Extraordinary was included in the collection Sometime, Never (Eyre and Spottiswoode), along with stories by John Wyndham and Mervyn Peake. On February 24, 1958, the play The Brass Butterfly, starring Alistair Sim, based on the story “The Ambassador Extraordinary,” premiered in Oxford. The performance was a success in many cities in Britain, and was shown on the capital’s stage for a month. The text of the play was published in July. In the fall of 1958, the Goldings moved to the village of Bowerchalke. Over the next two years, the writer suffered two bereavements: his father and mother died.

In 1959, the novel Free Fall was published; the work, the main idea of which, according to the author, was an attempt to show that “life is initially illogical until we ourselves impose logic on it,” is considered by many to be the strongest in his legacy. Reflections on the boundaries of a person’s free choice, presented in artistic form, differed from Golding’s first works in the absence of allegorical and strictly outlined plotlines; nevertheless, the development of basic ideas concerning the criticism of basic concepts about human life and its meaning was continued here.

In the fall of 1961, Golding and his wife went to the United States, where he worked for a year at Hollins Women’s Art College (Virginia). Here, in 1962, he began work on his next novel, The Spire, and also gave the first version of the Parable lecture, about the novel Lord of the Flies. Explaining in a 1962 interview the essence of his worldview regarding the main theme of his first novels, Golding said: “At heart I am an optimist. On an intellectual level, understanding that… the chances of humanity blowing itself up are about one in one, on an emotional level, I just don’t believe that it will do it.” That same year, Golding left Wordsworth’s school and became a professional writer. Speaking at a meeting of European writers in Leningrad in 1963, he formulated his philosophical concept, expressed in the novels that made him famous:

The facts of life lead me to the conviction that humanity is stricken with disease… This is what occupies all my thoughts. I look for this disease and find it in the most accessible place for me – in myself. I recognize this as part of our common human nature, which we must understand, otherwise it will be impossible to control. That’s why I write with all the passion I can muster…

The author’s worldwide recognition was promoted by the 1963 film Lord of the Flies, directed by Peter Brook.

1964—1983

One of Golding’s most important works is The Spire (1964). In a novel that firmly interweaves myth and reality, the author turned to exploring the nature of inspiration and reflecting on the price a person has to pay for the right to be a creator. In 1965, the collection “The Hot Gates” was published, which included journalistic and critical works written in 1960-1962 for the Spectator magazine. The essays about childhood (“Billy the Kid,” “The Ladder and the Tree”) and the essay “Parable” were noted as outstanding, in which the author tried to answer all the questions asked about the novel “Lord of the Flies” by readers and experts. By this point, Golding had gained both mass popularity and critical authority. Then, however, there came a many-year pause in the writer’s work, when only short stories and short stories came out of his pen.

In 1967, a collection of three short stories was published under the general title “Pyramid”, united by the setting, provincial Stilburn, where eighteen-year-old Oliver experiences life as “a complex heap of hypocrisy, naivety, cruelty, perversity and cold calculation.” The work, autobiographical in some elements, evoked mixed responses; Not all critics considered it a complete novel, but many noted the unusual combination of social satire and elements of a psychological novel. The collection “The Scorpion God: Three Short Novels”, 1971, was received much warmer, three short stories of which take the reader to Ancient Rome (“Envoy Extraordinary”), to primitive Africa (“Klonk-klonk”) and to the coast Nile in the 4th millennium BC (“Scorpio God”). The book returned the writer to the more familiar genre of parable, which he used here to analyze philosophical issues of human existence that are relevant to modern times, but retained elements of social satire.

In subsequent years, critics were at a loss about what happened in the 1970s to the writer, who noticeably decreased his creative activity; The most gloomy forecasts were made related to the ideological crisis, the creative impasse into which the “tired prophet” from Salisbury allegedly reached. But in 1979, The Darkness Visible (the title of which was borrowed from Milton’s poem Paradise Lost, as the classic poet defined the Underworld) marked Golding’s return to great literature and was awarded the James Tait Black Memorial Prize. The very first scenes of the book, in which a small child with terrible burns emerges from the fire during the bombing of London, made critics again start talking about biblical analogies and the writer’s views on the problem of primordial, primeval Evil. Researchers noted that in the late 1970s, Golding seemed to have a “second wind”; over the next ten years, five books came out from his pen, in depth of problems and mastery of execution not inferior to his first works.

The novel Darkness Visible (1979) was followed by Rituals of Sailing (1980), which won the author the Booker Prize and marked the beginning of the Sea Trilogy, a socio-philosophical allegorical narrative about England, “sailing into the unknown on the waves of history.” In 1982, Golding published a collection of essays entitled “A Moving Target” (1982), and a year later he won the highest literary award.

Nobel Prize Award

In 1983, William Golding was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature “for novels that, with the clarity of realistic narrative art, combined with the variety and universality of myth, help to comprehend the human condition in the modern world.” It came as a surprise to many that Golding was chosen over another English candidate, Graham Greene. Moreover, one of the members of the Swedish Academy, literary critic Arthur Lunquist, voting against the election of Golding, said that this author is a purely English phenomenon and his works “are not of significant interest.” Lars Iyllensten gave a different assessment of the candidate’s works: “Golding’s novels and stories are not only gloomy moral teachings and dark myths about evil and treacherous destructive forces, they are also entertaining adventure stories that can be read for pleasure,” said a representative of the Swedish Academy. “His books excite and captivate. They can be read with pleasure and benefit without much effort… But at the same time they have aroused extraordinary interest among professional literary critics, who have discovered a huge layer of complexity and ambiguity in Golding’s work,” said an official statement from the Swedish Academy.

In his Nobel lecture, William Golding jokingly disavowed his reputation as a hopeless pessimist, saying that he was “a universal pessimist but a cosmic optimist.”

Twenty-five years ago, I was frivolously labeled as a pessimist, not realizing that this title would stick for a long time, just as, for example, the famous C-sharp minor prelude was attached to the name of Rachmaninov. Not a single audience would let him leave the stage until he performed it. Likewise, critics read my books until they find something that seems hopeless to them. And I can’t understand why. I myself do not feel this hopelessness<…>Thinking about the world ruled by science, I become a pessimist… However, I am an optimist when I think about the spiritual world, from which science is trying to distract me… We need more love, more humanity, more care.

W. Golding, Nobel speech, 1983

last years of life

In 1988, Golding received a Second Knighthood from Queen Elizabeth. Four years earlier, the writer published the novel The Paper Men, which caused fierce controversy in the Anglo-American press. It was followed by Close Quarters (1987) and Fire Down Below (1989). In 1991, the writer, who had recently celebrated his eightieth birthday, independently combined three novels into a cycle, which was published under one cover under the title “To the End of the World: The Sea Trilogy.”

In 1992, Golding learned that he was suffering from malignant melanoma; at the end of December the tumor was removed, but it became clear that the writer’s health was undermined. At the beginning of 1993, he began work on a new book, which he did not have time to complete. The novel The Double Tongue, restored from unfinished sketches and therefore a relatively small work telling (in the first person) the story of the soothsayer Pythia, was published in June 1995, two years after the death of the author.

William Golding died suddenly of a massive heart attack at his home in Perranworthol on June 19, 1993. He was buried in the church cemetery in Bowerchock, and the funeral service was served in Salisbury Cathedral under the very spire that inspired the writer one of his most famous works.

Creation

As literary critic A. A. Chameev noted, William Golding’s prose, “plastic, colorful, intense,” belongs to the most “bright phenomena of post-war British literature.” Golding’s works are characterized by drama, philosophical depth, variety and complexity of metaphorical language; behind the apparent simplicity and ease of narration in the author’s books, “hidden is the integrity and rigor of the form, the precise coherence of details.” According to W. Allen, each component of the writer’s work, while maintaining artistic independence, “works” on a predetermined philosophical concept, often contradictory and controversial, but “invariably dictated by sincere anxiety for the fate of man in a dislocated world; translated into the flesh and blood of artistic images, this concept turns the entire structure into a generalization of almost cosmic breadth.”

Golding’s concepts were mainly based on an extremely pessimistic attitude towards human nature and the prospects for its evolution. “The optimistic idea of the expediency and irreversibility of the historical process, faith in reason, in scientific progress, in social reconstruction, in the original goodness of human nature seem to Golding – in the light of the experience of the war years – nothing more than illusions that disarm a person in his desperate attempts to overcome the tragedy of existence “, wrote A. Chameev. In formulating his goals, the writer prioritized the problem of studying man with all his dark sides. “Man suffers from a monstrous ignorance of his own nature. The truth of this position is beyond doubt for me. I devoted my creativity entirely to solving the problem of what constitutes a human being,” he wrote in 1957.

Researchers have classified the genre of W. Golding’s works in different ways: “parable”, “parabola”, “philosophical-allegorical novel”, noting that his characters, as a rule, are torn out of everyday life and placed in circumstances where there are no such convenient loopholes as exist under normal conditions. The writer himself did not deny the parable nature of his prose; Moreover, he devoted a lecture to American students in 1962 to thoughts on this topic. Recognizing his commitment to myth-making, he interpreted “myth” as “the key to existence, revealing the ultimate meaning of existence and absorbing life experience entirely and without residue.” Researchers have noted the uniqueness of “Golding’s world”: its sparse population, often isolation (an island in “Lord of the Flies”, a plot of primeval forest in “The Descendants”, a lonely rock in the middle of the ocean in “Martin the Thief”). It is the spatial limitation of the field of action that opens up the author “space for modeling various kinds of extreme (borderline – in existentialist terminology) situations,” thereby ensuring “the purity of experience,” believed A. Chameev.

Reviews from critics

The work of William Golding has always evoked contradictory, often polar, responses and assessments. The American critic Stanley E. Hyman called him “the most interesting modern English writer.” The English novelist and critic W. S. Pritchett shared the same opinion. However, the allegorical nature of Golding’s prose gave critics cause for much controversy. Opinions have been expressed that allegories burden the narrative outline of his books; To many, the author’s writing style seemed pretentious. Frederick Karl criticized Golding for his “failure…to provide an intellectual basis for his themes” and for his “didactic tone.” “His eccentric themes lack the balance and maturity that would indicate literary mastery,” the same critic argued. Jonathan Raban considered Golding not so much a novelist as a “literary preacher”, concerned exclusively with solving global issues of existence. “His books follow the preacher tradition at least as much as they follow the tradition of the novel. Golding is not very good at reproducing reality; fictional events in his novels occur as they occur in parables. His prose style lacks melody and often appears awkward,” Raban wrote in The Atlantic.

“Lord of the Flies” and “Descendants”

Initial responses to Golding’s debut novel were muted. As the novel’s reputation and popularity grew, attitudes towards it began to change. Literary critics, who initially perceived the work as just another adventure story, soon began to build entire theoretical structures around it. Lord of the Flies was eventually included in mainstream educational programs; Moreover, in terms of the level of interest in it from analysts, it turned out to be comparable to the two main books of J. Orwell. In the United States, as Dwight Garner, a columnist for the New York Times, noted, it was Lord of the Flies that “replaced Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye as the Bible of unhappy childhoods.”

The main idea of the novel, which is that “the so-called civility of man is something, at best, only superficial” (James Stern, New York Times Book Review), criticism formulated following the author’s own statements about his brainchild. From this point on, Golding began to be considered the exponent of a pessimistic view of human nature; a master of allegory, using the genre of the novel to analyze the ongoing struggle in man between the civilized “I” and his dark primitive nature. Some scholars have seen the presence of biblical motifs in Lord of the Flies (David Anderson believed that it was “a complex version of the story of Cain, the man who, after his signal fire failed to work, killed his brother”), noting that the novel “explores the origins of the moral degradation of humanity.” C. B. Cox called Lord of the Flies in 1960 “perhaps the most important novel written in the 1950s.” In The Times list of “The Best 60 Books of the Past 60 years” the novel was ranked as the best novel of 1954. Lionel Trilling attributed the work to the significance of a turning point in the history of modern English literature: after it, “…God may have died, but the Devil flourished – especially in English public schools.”

Golding’s second novel, The Heirs, was seen, on the one hand, as an implicit continuation of the first, on the other, as a polemic with the Outline of History by H. G. Wells, who professed an optimistic, rationalist view of human progress. The Times Literary Supplement noted that these two works are even somewhat close stylistically. Golding recalled that his rationalist father considered this particular work of Wells as “the ultimate truth.” Peter Green (A Review of English Literature), noting the internal connection between The Descendants and Lord of the Flies, wrote that Golding in his second novel “… merely created a second working model in order to show true human nature from a different angle.” . Another British critic, Oldsey, continued the same parallel in a religious vein: both novels, in his view, explore human regression – not in a Darwinian, but in a biblical way. The boys from Lord of the Flies regress, the Neanderthals are pushed forward by aliens towards progress, but the result is the same. Taken together, Golding’s first two novels are, according to Lawrence R. Rice (Wolf Masks: Violence in Contemporary Fiction), “a study of human nature that foregrounds violence; aggression directed by man against his own kind.”

Novels 1959-1964

The “primitive” period in Golding’s work ended with the publication of the third novel, Martin the Thief, but critics noted echoes of familiar ideas in it. The allegory of the ridiculousness of the petty struggle of a person whose “apparent existence is a kind of voluntary purgatory, a refusal to accept God’s mercy and die” was also considered in biblical terms: for example, the Southern Review noted that the episodes of the work are arranged “in a six-day structure … of a near-death experience”, which , including the timelessness in which the islander’s fictional events take place, “serves as a terrifying parody of the six days of Creation…”. “Darkness [for the author] becomes a universal symbol: it is the darkness of a being deprived of the ability to see itself, … the darkness of the subconscious, the darkness of sleep, death and beyond death – the sky,” wrote Stephen Medcalf in the book “William Golding”.

The novel “Free Fall” (1958), dedicated to the study of the question of the limits of human free choice, differed from Golding’s first works in the absence of any allegory. At the same time, criticism also noticed here a continuation of a number of lines begun in early novels: exploring the transition from childhood innocence to adulthood, which is characterized by a complete loss of internal freedom, the author questioned the basic concepts of human life and its meaning. Stephen Medcalf saw parallels with Dante in Free Fall (the hero’s first lover, who later ends up in a mental hospital, is named Beatrice), noting that Golding in his novel traces the fall of man directly – where Dante is limited to hints.

In the novel “The Spire” (1964), W. Golding, as S. Medcalf wrote, again showed “interest in the clouded areas of human character,” continuing “the study of the human will, ready to sacrifice everything to itself.” The story of Abbot Jocelyn, who finds himself in the grip of an obsession with his own “mission,” has received many interpretations: for example, the New York Review of Books called Spire “a book about foresight and the cost of it,” which “touches on the theme of motivation in art and prayer,” and the spire is used – as a symbol, on the one hand, phallic, on the other – as the personification of the intercourse of two principles: human and divine. The New York Times Book Review noted that “The Spire” can also be interpreted as the author’s accurate description of his artistic method, the essence of which is an attempt to “ascend high while remaining chained to the earth.” “Mr. Golding in his aspirations rises like a vine, clinging to any firmament. This is especially evident in The Spire, where every stone, every scaffolding, every cornice and knot is used by the author to pull himself up to the heavens,” wrote Nigel Dennis. Despite the fact that Golding himself emphasized the “earthly” meaning of the book’s ending (Jocelyn the fanatic dies, having felt the beauty of the world around him before his death), he also noted: the main character perceives his own mania as divine madness, believing that God himself pushes a person to “crazy things “in the name of self-glorification. The English critics M. Kinkead-Weeks and I. Gregor considered “The Spire” to be a turning point in Golding’s work, which from then on bifurcated into two channels: metaphysical and social.

1967–1979: “Pyramid” and “Visible Darkness”

Not all literary critics considered “The Pyramid” – a collection of three short stories united by the setting, the provincial English town of Stilbourne, – a novel. Some of them called this work the weakest in the writer’s legacy, others noted its dissimilarity from the rest: according to the Times Literary Supplement, the book is “not a parable, does not contain obvious allegories, does not tell about some simplified or distant world. It belongs to a different, more familiar tradition in English literature: an unpretentious, realistic novel about a boy growing up in a small town, the kind of book that H. G. Wells might have written if he had been more careful with his writing style.”

The Scorpion God: Three Short Novels, a 1971 collection, was received more favorably by critics. Thus, the Times Literary Supplement reviewer considered it a demonstration of “purely Goldingian gift.” The title story, according to the critic, takes the reader into the world of Ancient Egypt, “applying familiar criteria to the unfamiliar… It is a brilliant tour de force, like The Heirs, perhaps on a more modest scale.”

Golding’s novel The Visible Darkness was published in 1979. As critic Samuel Hines (Washington Post Book World) noted, after missing fifteen years, Golding returned to the world of the novel virtually unchanged, still the same “moralist and creator of parables”:

The moralist is required to believe in the existence of good and evil, and Golding does; in general, we can say that the study of the nature of good and evil is its only theme. The writer of parables must believe that the moral meaning can be expressed in the very fabric of the story, indeed, that some aspects of this meaning can only be expressed in this way – again this is the Goldingian principle.

— Samuel Hines, Washington Post Book World, 1979

Many researchers noted the author’s return to biblical allegories. It was in these categories that Susan F. Schaeffer (Chicago Tribune Book World) considered the confrontation between Mattie, a boy miraculously saved in a fire who becomes clairvoyant and personifies the light, and twin sisters Tony and Sophie Stanhope, who discover the “temptations of darkness.”

Golding’s last novels

The series “To the End of the World: The Sea Trilogy” (1991) included the novels “Rituals of Sailing” (1980), “Close Neighborhood” (1987) and “The Fire Below” (1989). The historical saga, set in the 18th century, returned the writer to the genre of allegory: it is generally accepted that the ship here serves as a symbol of the British Empire. Blake Morrison (reviewer for the New Statesman) noted that the first novel of the trilogy echoes Lord of the Flies – at least in the basic idea that man, as a “fallen creature”, is capable of “atrocities for which there is no description.” words.” A ship with passengers on board, remaining a real and life-like space (according to A. Chameev), “…metaphorically performs the function of not spatial relations at all: is a micromodel of society in its British version, and at the same time a symbol of all humanity, vain, torn apart by contradictions, moving amidst dangers in an unknown direction.”

In the second novel of the trilogy, Close Neighborhood, which continues the story of Talbot’s voyage to Australia, the ship appears before the reader at a different stage of its existence: it symbolizes Britain on the verge of collapse. The work raised many questions among critics: for example, Los Angeles Times Book Review reviewer Richard Howe wrote that the second novel is difficult to perceive outside the general context; in itself, at a minimum, is puzzling: “This is not an allegory or fantasy, not adventure prose, or even a completed novel, since it has a beginning and, it seems, a middle, but its end seems to be placed in an indefinite future.”

Quill and Quire reviewer Paul Stewy called the trilogy’s finale, The Fire Below, “ambitious” and “generally successful,” with a thrilling ending. W. L. Webb (New Statesman & Society), although he considered the second and third parts of the trilogy inferior to the first, noted that “the reader’s attention is held … by Golding’s magical pictures of the sea, the faces looming on the deck on a moonlit night, the eerie shadows, cast by the figures of people in the fog amid the drizzle, lightning and the roar of the wind, a swarm of bees of sailors rushing towards the cliffs on a damaged ship.” “There is nothing else like this in our literature,” the reviewer concluded.

The novel Paper People (1984), which centers on a conflict between an elderly British writer and an ambitious American literary critic, marked the first (after Pyramid) return to the genre of social comedy and received mixed reviews in the Anglo-American press, turning out to be the most controversial the author’s work. The main idea of this “farce”, according to Michael Ratcliffe of the London Times, was that “biography is the subject of a commercial scam.” Blake Morrison, however, again discovered the possibility of drawing a religious parallel here (“At one level, this is the protection of talent from the threat hanging over the living writer … in the form of the dead hand of scientism. At another level, Tucker can be seen either as a Christ-like figure, atoning for the sins of Barclay, or as Satan… whose temptations Barclay must reject”). For the most part, critics found the novel not to meet the highest standards of Golding’s craftsmanship: “Judging by the tired, capricious tone of the narrative, Mr. Golding resembles his hero not only in appearance” (Michiko Kakutani, New York Times); “Whatever a writer produces after winning a Nobel Prize is disappointing, and new novel… is no exception” (David Lodge, New Republic).

Family

The writer’s father, Alec Golding, taught science and served as deputy headmaster at Marlborough School, from which his son later graduated. Golding Sr. wrote several textbooks on botany, chemistry, zoology, physics and geography, and was also an excellent musician: he played the violin, piano, viol, cello and flute. As noted later, it was the writer’s father, an enthusiast and polymath, in love with science and always surrounded by a crowd of students, who served as the prototype for one of the characters in the novel Free Fall – a science teacher named Nick Shales. In November 1958, Alec Golding was diagnosed with cancer; he underwent surgery to remove the tumor, but on December 12 he died suddenly in hospital from a heart attack.

The writer’s mother, Mildred Golding, was a woman of strong character and strong convictions, a suffragist and feminist. Two lines – scientific-rationalistic (paternal) and socially active (maternal) – for some time equally influenced the formation of the boy’s character; the first of them ultimately prevailed. Although, as Joyce T. Forbes later noted, it was the mother’s comment made about the sinking of the Titanic, regarding the fact that man is defenseless against the forces of nature, in a sense, that was the seed from which Golding’s critical attitude towards the “hard-headed” grew. rationalism.” Mildred Golding died in 1960.

Personal life

In 1939, William Golding married Anne Brookfield, an analytical chemist; At the same time, the couple moved to Salisbury, Wiltshire, where they lived most of their lives. In September 1940, the Goldings had a son, David; daughter Judith Diana was born in July 1945. Anne Golding died on December 31, 1995 and was buried with her husband in Bowerchoke Cemetery.

Golding’s daughter Judith Carver wrote a biography, Lovers’ Children (Faber & Faber, May 2011), to mark the centenary of the writer’s birth.

“The title of the book partly refers to the saying: ‘Children of lovers are always orphans; our parents were too passionate about each other and each other …,” Carver said in an interview with the Guardian. The author claimed that her father “was in many ways a very kind, understanding, sweet, warm and cheerful man,” remarking: “Strangely, no one believes it: everyone is convinced that he was extremely gloomy.” In many ways, this view of Golding’s character traits was facilitated by the publication in 2009 of John Carey’s biography “William Golding: the Man Who Wrote Lord of the Flies,” which, despite the scandalous nature of some of the revelations, received the full support of Judith Carver. The author of the book focused on those personality traits of Golding that made the writer a “monster” in his own eyes.

Character traits

Golding had an unhappy childhood: according to John Carey’s biography, he “grew up as a timid, hypersensitive, fearful boy” and suffered from loneliness and alienation. The author of the biography believed that the psychological problems of Golding’s childhood were largely predetermined by deep class motives: his father, an impoverished intellectual, taught at a high school, which was located not far from the elite Marlborough College. By their appearance alone, the students of this institution made young Golding feel “dirty and humiliated.” His desire for literary success was largely motivated by a “thirst for revenge”: “To tell the truth, in the depths of my soul I had one desire: to wipe my nose with this Marlboro …,” the Nobel laureate later admitted. Class prejudices later haunted Golding: at Brazenose College he was given unflattering acronyms: “N.T.S.” (“not top shelf”, “not the highest class”) and “N.Q.” (“Not quite”, “not quite ”). The writer carried his hatred of snobbery throughout his life: in one of his reviews, he even admitted that he always dreamed of “wrapping Eton with a mile or two of wire, loading several hundred tons of TNT into it” with a detonator and for a minute “…feeling like Jehovah.”

People who interacted with Golding in the last years of his life paid attention to the “marine” stamp that lay on his entire appearance. “He looked more like an old man who was about to start advertising fish fins or burst into a sailor’s song, but not at all like a Nobel Prize winner who created several highly original works of the last century,” noted a Telegraph Books reviewer. In 1966, when the BBC asked the sculptor and artist Michael Ayrton to characterize Golding the man, he replied: “a cross between Captain Hornblower and St. Augustine.” As R. Douglas-Fairhurst noted in this regard, in the second part of this comparison we could talk, perhaps, “about Augustine before he accepted Christianity.” Golding wrote about himself in his diary: “Someday, if my literary reputation remains at the same high level, people will begin to study my life and discover that I am a monster.”

As John Carey noted in his biography “William Golding: The Man Who Wrote Lord of the Flies,” there was a certain dark side to the writer’s character even before the war, the origins of which remained unclear. The biographer assumed that some long-standing “monstrous” episode had taken place in the writer’s life; “hidden obscenity”, the essence of which remained hidden to outsiders. Perhaps this had to do with the experiences of early childhood: it is known that Golding’s mother suffered from a strange mental disorder, which “at nightfall turned her into a dangerous maniac: she threw knives, mirror fragments, and kettles of boiling water at little William.” Daughter Judith confirmed: the writer “… despised himself, and the roots of this feeling were very deep. Sometimes he treated it jokingly, “getting off” with self-deprecating ridicule, but sometimes it was felt that “somewhere in him lies” something so dark that he simply could not live with it.

In connection with the novel Free Fall, which vividly and in detail described the details of the psychological torture to which the main character was subjected to in a Hitler prisoner of war camp, Golding himself noted that he “understood the Nazis” because “he himself is one by nature.” The writer’s diaries contain descriptions of several actions he committed, of which he was ashamed all his life; for example, the story of how he shot a rabbit in Cornwall, and how it looked at the killer before falling – “with an expression of surprise and anger on its face.”

One of the most scandalous episodes of Carey’s biography concerns Golding’s description of his failed attempt to rape a fifteen-year-old girl. The writer justified his action by the fact that she, “flawed by nature,” at the age of 14 was “sexy as a monkey.” It is believed that this episode was used indirectly in the novel Martin the Thief. True, Judith Carver was not too shocked by the fragment of her biography describing the “inept” rape: she said that her father belonged to a sexually complex generation and could here exaggerate his own cruelty. However, Carver’s husband claimed that all his life the writer “practised in humiliating those around him – of course, in those cases when he deigned to notice their existence at all.”

Judging by some diary entries, Golding often seemed to practice some episodes of his future works on real people. In this regard, descriptions concerning his teaching activities aroused particular interest. It is known that, having started rehearsals for “Julius Caesar,” he placed special emphasis on ensuring that all the boys “felt the sensations of a crowd thirsting for blood.” At the same time, he explained in detail to one of the young actors how to use the dagger (“stick it in the stomach, rip it open with an upward movement”). Having organized a school expedition to Neolithic excavations near Salisbury, Golding the teacher divided the boys into two groups, one of which defended the fortification, the other attacked it. Both incidents reminded reviewers of corresponding episodes in Lord of the Flies and Descendant. All this, Douglas-Fairhurst wrote, indicates that the writer was “tempted by the possibility of using life situations to practice the elements of prose.” At times, according to the reviewer, Golding “treated students like wasps in a jar that could be shaken well just to get a glimpse of the result.” It is also known that the writer was haunted by nightmares, some of which resembled sketches for certain events in novels and often became such later.

Golding was not known for his aggressiveness; on the contrary, according to Carey’s biography, he was “a man of many sorrows who walked through life, overcoming one obstacle after another with unbending tenacity.” The writer “was afraid of heights, pricks, crustaceans, insects and everything that crawls… Being an experienced sailor, he had no sense of direction; one of his boats sank. He could get lost while driving a car, being several miles from his own home.” It is known that a significant portion of these problems were associated with alcohol abuse. Not being a clinical alcoholic, Golding drank a lot, went on binges – that’s when he committed his wildest antics. One day, waking up in the house of London acquaintances in a panic from his own nightmare, he jumped up and tore into pieces a Bob Dylan doll, because he imagined that Satan himself had appeared before him in this guise. The Guardian reviewer noted that not only in his novels, but also in his life, the writer constantly fought with “demons swarming in his head”; felt a continuous struggle within himself between “religiosity and rationality, myths and science.” At the same time, R. Douglas-Fairhurst noted: the facts set out in the biography of John Carey show the reader not so much a “monster” as a man who “recognized in himself a monster living in all of humanity”: therefore, he has a morbid interest in violence and suffering and everything “that is on the wrong side of civilization.” Golding, according to the Telegraph reviewer, had the ability to both sense evil within himself and sympathize with those who were victims of cruelty.

List of works, Poetry

Poems (1934)

Drama

The Brass Butterfly (1958)

Novels

Lord of the Flies (1954)

The Inheritors (1955)

Pincher Martin (1956)

Free Fall (1959)

The Spire (1964)

The Pyramid (1967)

Darkness Visible (1979) (James Tait Black Memorial Prize)

To the Ends of the Earth (trilogy)

Rites of Passage (1980) (Booker Prize)

Close Quarters (1987)

Fire Down Below (1989)

The Paper Men (1984)

The Double Tongue (posthumous publication 1995)

Collections

The Scorpion God (1971)

“The Scorpion God”

“Clonk Clonk”

“Envoy Extraordinary”

Non-fiction

The Hot Gates (1965)

A Moving Target (1982)

An Egyptian Journal (1985)

Unpublished works

Seahorse was written in 1948. It is a biographical account of sailing on the south coast of England in the summer of 1947 and contains a short passage about being in training for D-Day.

Circle Under the Sea is an adventure novel about a writer who sails to discover archaeological treasures off the coast of the Scilly Isles.

Short Measure is a novel set in a British school akin to Bishop Wordsworth’s.