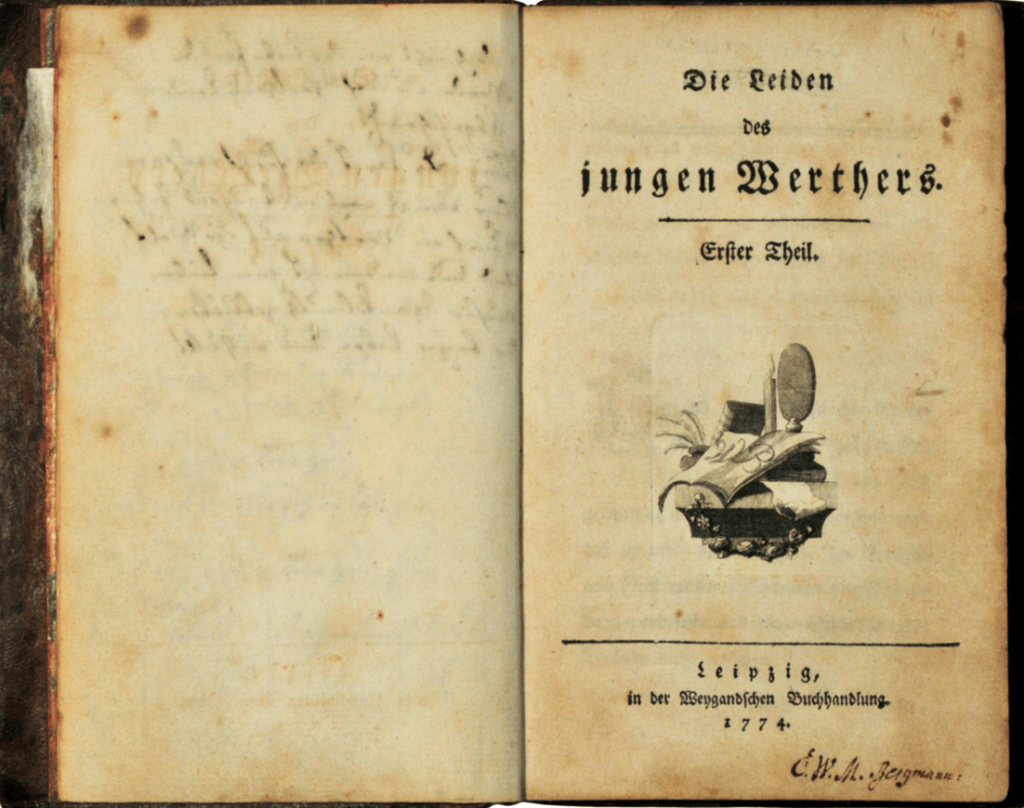

The Sorrows of Young Werther, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Contents

The Sorrows of Young Werther

Book One

Book Two

Notes

Book One

May 4th, 1771

I can’t tell you how glad I am to have got away. Dear friend, how strange is the human heart! I love you, we were inseparable—yet I can leave you and be content. I know you will forgive me.

Were not all my attachments designed by fate to intimidate a heart like mine? Poor Leonore! But I was not to blame. Was it my fault that, while her headstrong sister charmed and amused me, a passion for me developed in poor Leonore’s heart? Yet I ask myself—am I entirely blameless? Did I perhaps encourage her? Didn’t I quite frankly enjoy her completely sincere and natural outbursts, which often made the two of us laugh, although there was really nothing laughable about them? Didn’t I…oh, what is man made of that he may reproach himself? I shall do better in the future, my dear friend, I promise you. I shall stop dwelling on the petty wrongs of providence, as has been my wont. I intend to enjoy the present and let the past take care of itself.

Of course, best of friends, you are right—there would be less misery in this world if man were not so ever-ready to recall past evils rather than put up with the indifferent present. God knows why he is thus constituted!

Please tell my mother that I am doing my best to straighten out her affairs and will give her news of them as soon as I can. I have spoken to my aunt and must say that I didn’t find her to be the dreadful vehement woman with the kindest of hearts. I explained my mother’s complaint concerning her share of the inheritance, which has been withheld. She gave me the reasons for it and the conditions under which she would be willing to hand over all of it, which is even more than we are asking. But I really don’t feel like reporting about it now. Just tell her that everything will be all right. And in the course of this little transaction, my dear friend, I discovered again that misunderstandings and inertia cause perhaps more to go wrong in this world than slyness and evil intent. In any case, the latter are rarer.

And, by the way, I feel very well here. The solitude in these blissful surroundings is balm to my soul, and with its abundance, the youthful season of spring cheers my heart, which is still inclined to shudder. Every tree, every hedgerow is a bouquet. It makes me wish I were a ladybug and could fly in and out of the sea of wondrous scents and find all my nourishment there.

The town itself is not attractive, but I find ample compensation in the indescribable beauties of nature surrounding it. That was what induced the late Count von M. to set his garden on one of the numerous hillsides that intersect here, forming the loveliest valleys. The garden is not elaborate, and the moment you walk into it you feel that it was designed by a sensitive heart rather than a scientific gardener, a heart that sought to find its enjoyment there. I have shed a few tears myself for the departed gentleman, in the little, broken-down summerhouse that used to be his favorite haunt and now is mine. Soon I will be master of the garden. The gardener seems to think well of me, though I have been here only a few days, and I will see to it that he enjoys working for me.

May 10th

My whole being is filled with a marvelous gaiety, like the sweet spring mornings that I enjoy with all my heart. I am alone and glad to be alive in surroundings such as these, which were created for a soul like mine. I am so happy, best of friends, and so utterly absorbed by the sensations of a peaceful existence that my work suffers from it. I couldn’t draw now, not a line, yet was never a better painter. When the mists in my beloved valley steam all around me; when the sun rests on the surface of the impenetrable depths of my forest at noon and only single rays steal into the inner sanctum; when I lie in the tall grass beside a rushing brook and become aware of the remarkable diversity of a thousand little growing things on the ground, with all their peculiarities; when I can feel the teeming of a minute world amid the blades of grass and the innumerable, unfathomable shapes of worm and insect closer to my heart and can sense the presence of the Almighty, who in a state of continuous bliss bears and sustains us—then, my friend, when it grows light before my eyes and the world around me and the sky above come to rest wholly within my soul like a beloved, I am filled often with yearning and think, if only I could express it all on paper, everything that is housed so richly and warmly within me, so that it might be the mirror of my soul as my soul is the mirror of Infinite God…ah, my dear friend…but I am ruined by it. I succumb to its magnificence.

May 12th

I don’t know whether deceptive spirits haunt these parts or whether it is the glowing fantasies of my heart that make everything around me seem so blissful. Just outside town there is a spring to which I feel mysteriously drawn, like Melusina and her sisters.1 You walk down a short slope and at the bottom find yourself facing an archway from which about twenty steps descend to a place where clearest water gushes out of marble rock. The low wall that hems this spot in at the top, the tall trees all around it that conceal the coolness within, all suggest something mysterious. Not a day passes without my spending an hour there. Young girls come from town to fetch water, a simple and very necessary business—in days of old even the daughters of kings used to do it—and as I sit there, a patriarchal atmosphere comes to life all around me. I can see our forefathers meeting and courting at wells like this, and how good spirits hovered over all such places. Whoever can’t feel with me has never refreshed himself at a cool spring after a long excursion on a hot summer’s day.

May 13th

You ask whether you should send me books. Dear friend, I beg of you—don’t. I have no wish to be influenced, encouraged, or inspired any more. My heart surges wildly enough without any outside influence. What I need is a lullaby, and I have found an abundance of them in my beloved Homer. How often I have to calm my rebellious blood! You have never known anything so wildly fluctuating as this heart of mine. But, dear friend, I don’t have to tell you this—you, who have so often witnessed my transitions from grief to extravagant joy, from sweetest melancholy to pernicious passion. I coddle my heart like a sick child and give in to its every whim. But don’t tell a soul. There are people who would condemn me for it.

May 15th

The simple folk here already know me and seem to be fond of me, especially the children. At first, when I made efforts to join them and ask questions about this and that, a few thought I was making fun of them and were quite rude. But I didn’t let it bother me. I only felt keenly what I have noticed often—that persons of rank tend to keep their cold distance from the common man, as if they feared to lose something by such intimacy. And then, of course, there are those who shrink from all contact with simple people, and the tactless jokesters who talk down to them—they succeed only in making the poor souls more sharply aware than ever of their presumption. I know that we human beings were not created equal and cannot be, but I am of the opinion that he who keeps aloof from the so-called rabble in order to preserve the respect he feels is his due is just as reprehensible as the coward who hides from his enemies because he fears to be defeated by them.

Not long ago I came to the spring and found a young servant girl there. She had put her water jar on the lowest step and was looking around in the hope that a friend might come and help her place it on her head. I walked down the steps and faced her. “Would you like me to help you?” I asked. She blushed and replied, “Oh no, sir!” “Let’s not stand on ceremony,” I said. She adjusted the pad on her head, I helped her with her pitcher, she thanked me, and up she went!

May 17th

I have met all sorts of people, but I have yet to find the right companionship. I don’t know what my attractions are, but many people seem to like me and attach themselves to me. Then it pains me when our paths coincide for only a short way. You ask what the people are like here. All I can say is, as they are everywhere else. There is something coldly uniform about the human race. Most of them have to work for the greater part of their lives in order to live and the little freedom they have left frightens them to such an extent that