The Eye of Paris, Henry Miller

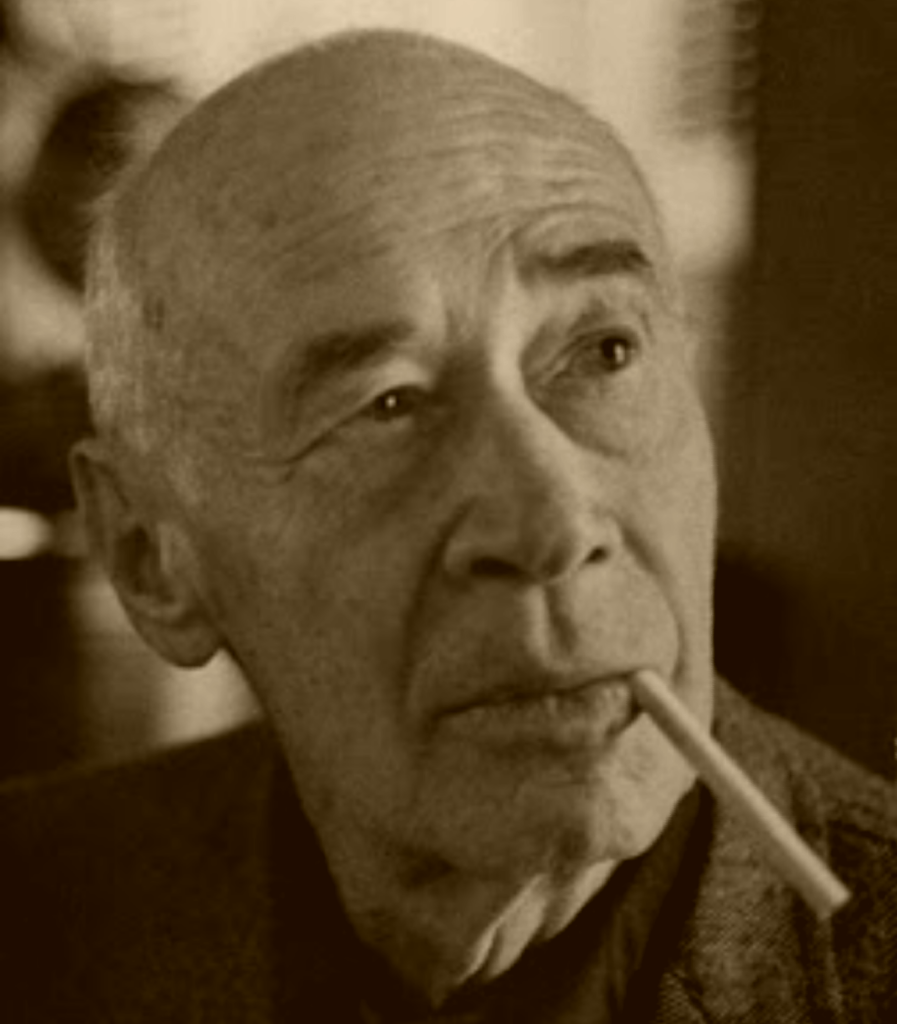

The Eye of Paris

BRASSAI HAS that rare gift which so many artists despise—normal vision. He has no need to distort or deform, no need to lie or to preach.

He would not alter the living arrangement of the world by one iota; he sees the world precisely as it is and as few men in the world see it because seldom do we encounter a human being endowed with normal vision.

Everything to which his eye attaches itself acquires value and significance, a value and significance, I might say, heretofore avoided or ignored. The fragment, the defect, the commonplace—he detects in them what there is of novelty or perfection.

He explores with equal patience, equal interest, a crack in the wall or the panorama of a city. Seeing becomes an end in itself. For Brassai is an eye, a living eye.

When you meet the man you see at once that he is equipped with no ordinary eyes. His eyes have that perfect, limpid sphericity, that all-embracing voracity which makes the falcon or the shark a shuddering sentinel of reality.

He has the eyeball of the insect which, hypnotized by its myopic scrutiny of the world, raises its two huge orbs from their sockets in order to acquire a still greater flexibility.

Eye to eye with this man you have the sensation of a razor operating on your own eyeball, a razor which moves with such delicacy and precision that you are suddenly in a ball room in which the act of undressing follows upon the wish.

His gaze pierces the retina like those marvelous probes which penetrate the labyrinth of the ear in order to sound for dead bone, which tap at the base of the skull like the dull tick of a watch in moments of complete silence.

I have felt the penetration of his gaze like the gleam of a searchlight invading the hidden recesses of the eye, pushing open the sliding doors of the brain. Under that keen, steady gaze I have felt the seat of my skull glowing like an asbestos grill, glowing with short, violet waves which no living matter can resist.

I have felt the cool, dull tremors in every vertebra, each socket, each nodule, cushion and fiber vibrating at such a speed that the whole backbone together with my rudimentary tail is thrown into incandescent relief.

My spine becomes a barometer of light registering the pressure and deflection of all the waves which escape the heavy, fluid substance of matter. I feel the feathery, jubilant weight of his eye rising from its matrix to brush the prisms of light.

Not the eye of a shark, nor a horse, nor a fly, not any known flexible eye, but the eye of a coccus newborn, a coccus travelling on the wave of an epidemic, always a millimeter in advance of the crest. The eye that gloats and ravages.

The eye that precedes doom. The waiting, lurking eye of the ghoul, the torpid, monstrously indifferent eye of the leper, the still, all-inclusive eye of the Buddha which never closes. The insatiable eye.

It is with this eye that I see him walking through the wings of the Folies-Bergère, walking across the ceiling with sticky, clinging feet, crawling on all fours over candelabras, warm breasts, crinolines, training that huge, cold searchlight on the inner organs of a Venus, on the foam of a wave of lace, on the cicatrices that are dyed with ink in the satin throat of a puppet, on the pulleys that will hoist a Babylon in paint and papier-mâché, on the empty seats which rise tier upon tier like layers of sharks’ teeth.

I see him walking across the proscenium with his beautiful suede gloves, see him peeling them off and tossing them to the inky squib which has swallowed the seats and the glass chandeliers, the fake marble, the brass posts, the thick velvet cords and the chipped plaster.

I see the world of behind the scenes upside down, each fragment a new universe, each human body or puppet or pulley framed in its own inconceivable niche. I see the lovely Venus prone and full athwart her strange axis, her hair dipped in laudanum, her mouth bright with asphodels; she lies in the neap of the tide, taut with starry sap, her toes tinctured with light, her eyes transfixed.

He does not wait for the curtain to rise; he waits for it to fall. He waits for that moment when all the conglomerations artificially produced resolve back into their natural component entities, when the nymphs and the dryads strewing themselves like flowers over the floor of the stage gaze vacantly into the mirror of the tank where a moment ago, tesselated with spotlights, they swam like goldfish.

Deprived of the miracle of color, registering everything in degrees of black and white, Brassai nevertheless seems to convey by the purity and quality of his tones all the effects of sunlight, and even more impressively the effects of night light.

A man of the city, he limits himself to that spectacular feast which only such a city as Paris can offer. No phase of cosmopolitan life has escaped his eye. His albums of black and white comprise a vast encyclopaedia of the city’s architecture, its growth, its history, its origins.

Whatever aspect of the city his eye seizes upon the result is a vast metaphor whose brilliant arc, studded with incalculable vistas backward and forward, glistens now like a drop of dew suspended in the morning light.

The Cemetery Montmartre, for example, shot from the bridge at night is a phantasmagoric creation of death flowering in electricity, the intense patches of night lie upon the tombs and crosses in a crazy patchwork of steel girders which fade with the sunlight into bright green lawns and flower beds and graveled walks.

Brassai strikes at the accidental modulations, the illogical syntax, the mythical juxtaposition of things, at that anomalous, sporadic form of growth which a walk through the streets or a glance at a map or a scene in a film conveys to the sleeping portion of the brain. What is most familiar to the eye, what has become stale and commonplace, acquires through the flick of his magic lens the properties of the unique.

Just as a thousand diverse types may write automatically and yet only one of them will bear the signature of André Breton, so a thousand men may photograph the Cemetery Montmartre but one of them will stand out triumphantly as Brassai’s.

No matter how perfect the machine, no matter how little of human guidance is involved, the mark of personality is always there. The photograph seems to carry with it the same degree of personality as any other form or expression of art.

Brassai is Brassai and Man Ray is Man Ray. One man may try to interfere as little as possible with the apparatus, or the results obtained from the apparatus; the other may endeavor to subjugate it to his will, to dominate it, control it, use it like an artist. But no matter what the approach or the technique involved the thing that registers is the stamp of individuality.

Perhaps the difference which I observe between the work of Brassai and that of other photographers lies in this—that Brassai seems overwhelmed by the fullness of life. How else are we to explain that a chicken bone, under the optical alchemy of Brassai, acquires the attributes of the marvelous, whereas the most fantastic inventions of other men often leave us with a sense of unfulfillment?

The man who looked at the chicken bone transferred his whole personality to it in looking at it; he transmitted to an insignificant phenomenon the fullness of his knowledge of life, the experience acquired from looking at millions of other objects and participating in the wisdom which their relationships one to another inspired.

The desire which Brassai so strongly evinces, a desire not to tamper with the object but regard it as it is, was this not provoked by a profound humility, a respect and reverence for the object itself?

The more the man detached from his view of life, from the objects and identities that make life, all intrusion of individual will and ego, the more readily and easily he entered into the multitudinous identities which ordinarily remain alien and closed to us. By depersonalizing himself, as it were, he was enabled to discover his personality everywhere in everything.

Perhaps this is not the method of art. Perhaps art demands the wholly personal, the catalytic power of will. Perhaps.

All I know is that when I look at these photographs which seem to have been taken at random by a man loath to assert any values except what were inherent in the phenomena, I am impressed by their authority.

I realize in looking at his photos that by looking at things aesthetically, just as much as by looking at things moralistically or pragmatically, we are destroying their value, their significance.

Objects do not fade away with time: they are destroyed! From the moment that we cease to regard them awesomely they die. They may carry on an existence for thousands of years, but as dead matter, as fossil, as archaeologic data.

What once inspired an artist or a people can, after a certain moment, fail to elicit even the interest of a scientist. Objects die in proportion as the vision of things dies. The object and the vision are one. Nothing flourishes after the vital flow is broken, neither the thing seen, nor the one who sees.

It happens that the man who introduced me to Brassai is a man who has no understanding