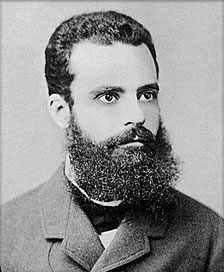

Vilfredo Federico Damaso Pareto (UK: /pæˈreɪtoʊ, -ˈriːt-/ parr-AY-toh, -EE-, US: /pəˈreɪtoʊ/ pə-RAY-toh, Italian: [vilˈfreːdo paˈreːto], Ligurian: [paˈɾeːtu]; born Wilfried Fritz Pareto; 15 July 1848 – 19 August 1923) was an Italian polymath, whose areas of interest included sociology, civil engineering, economics, political science, and philosophy. He made several important contributions to economics, particularly in the study of income distribution and in the analysis of individuals’ choices. He was also responsible for popularising the use of the term “elite” in social analysis.

He introduced the concept of Pareto efficiency and helped develop the field of microeconomics. He was also the first to claim that income follows a Pareto distribution, which is a power law probability distribution. The Pareto principle was named after him, and it was built on his observations that 80% of the wealth in Italy belonged to about 20% of the population. He also contributed to the fields of sociology and mathematics.

Biography

Pareto was born of an exiled noble Genoese family on 15 July 1848 in Paris, the centre of the popular revolutions of that year. His father, Raffaele Pareto (1812–1882), was an Italian civil engineer and Ligurian marquis who had left Italy much as Giuseppe Mazzini and other Italian nationalists had. His mother, Marie Metenier, was a French woman. Enthusiastic about the revolutions of 1848 in the German states, his parents named him Wilfried Fritz, which became Vilfredo Federico upon his family’s move back to Italy in 1858. In his childhood, Pareto lived in a middle-class environment, receiving a high standard of education, attending the newly created Istituto Tecnico Leardi where Ferdinando Pio Rosellini was his mathematics professor. In 1869, he earned a doctorate in engineering from what is now the Polytechnic University of Turin (then the Technical School for Engineers), with a dissertation entitled “The Fundamental Principles of Equilibrium in Solid Bodies”. His later interest in equilibrium analysis in economics and sociology can be traced back to this dissertation. Pareto was among the contributors to the Rome-based magazine La Ronda between 1919 and 1922.

From civil engineer to classical liberal economist

For some years after graduation, he worked as a civil engineer, first for the state-owned Italian Railway Company and later in private industry. He was manager of the Iron Works of San Giovanni Valdarno and later general manager of Italian Iron Works.

He did not begin serious work in economics until his mid-forties. He started his career as a fiery advocate of classical liberalism, besetting the most ardent British liberals with his attacks on any form of government intervention in the free market. In 1886, he became a lecturer on economics and management at the University of Florence. His stay in Florence was marked by political activity, much of it fueled by his own frustrations with government regulators. In 1889, after the death of his parents, Pareto changed his lifestyle, quitting his job and marrying a Russian woman, Alessandrina Bakunina.

Economics and sociology

In 1893, he succeeded Léon Walras to the chair of Political Economy at the University of Lausanne in Switzerland where he remained for the rest of his life. He published there in 1896-1897 a textbook containing the Pareto distribution of how wealth is distributed, which he believed was a constant “through any human society, in any age, or country”. In 1906, he made the famous observation that twenty per cent of the population owned eighty per cent of the property in Italy, later generalised by Joseph M. Juran into the Pareto principle (also termed the 80–20 rule).

Pareto maintained cordial personal relationships with individual socialists, but he always thought their economic ideas were severely flawed. He later became suspicious of their motives and denounced socialist leaders as an ‘aristocracy of brigands’ who threatened to despoil the country and criticized the government of the Italian statesman Giovanni Giolitti for not taking a tougher stance against worker strikes. Growing unrest among labour in the Kingdom of Italy led him to the anti-socialist and anti-democratic camp. His attitude towards Italian fascism in his last years is a matter of controversy.

Pareto’s relationship with scientific sociology in the age of the foundation is grafted in a paradigmatic way at the moment in which he, starting from the political economy, criticizes positivism as a totalizing and metaphysical system devoid of a rigorous logical-experimental method. In this sense we can read the fate of the Paretian production within a history of the social sciences that continues to show its peculiarity and interest for its contributions in the 21st century. The story of Pareto is also part of the multidisciplinary research of a scientific model that privileges sociology as a critique of cumulative models of knowledge as well as a discipline tending to the affirmation of relational models of science.

Personal life

In 1889, Pareto married Alessandrina Bakunina, a Russian woman. She left him in 1902 for a young servant. Twenty years later in 1923, he married Jeanne Regis, a French woman, just before his death in Geneva, Switzerland on 19 August 1923.

Sociology

Pareto’s later years were spent in collecting the material for his best-known work, Trattato di sociologia generale (1916) (The Mind and Society, published in 1935). His final work was Compendio di sociologia generale (1920).

In his Trattato di Sociologia Generale (1916, rev. French trans. 1917), published in English by Harcourt, Brace in a four-volume edition edited by Arthur Livingston under the title The Mind and Society (1935), Pareto developed the notion of the circulation of elites, the first social cycle theory in sociology. He is famous for saying “history is a graveyard of aristocracies”.

Pareto seems to have turned to sociology for an understanding of why his abstract mathematical economic theories did not work out in practice, in the belief that unforeseen or uncontrollable social factors intervened. His sociology holds that much social action is nonlogical and that much personal action is designed to give spurious logicality to non-rational actions. We are driven, he taught, by certain “residues” and by “derivations” from these residues. The more important of these have to do with conservatism and risk-taking, and human history is the story of the alternate dominance of these sentiments in the ruling elite, which comes into power strong in conservatism but gradually changes over to the philosophy of the “foxes” or speculators. A catastrophe results, with a return to conservatism; the “lion” mentality follows. This cycle might be broken by the use of force, says Pareto, but the elite becomes weak and humanitarian and shrinks from violence.

Among those who introduced Pareto’s sociology to the United States were George Homans and Lawrence J. Henderson at Harvard, and Paretian ideas gained considerable influence, especially on Harvard sociologist Talcott Parsons, who developed a systems approach to society and economics that argues the status quo is usually functional. The American historian Bernard DeVoto played an important role in introducing Pareto’s ideas to these Cambridge intellectuals and other Americans in the 1930s. Wallace Stegner, in his biography of DeVoto, recounts these developments and says this about the often misunderstood distinction between “residues” and “derivations”: “Basic to Pareto’s method is the analysis of society through its non-rational ‘residues,’ which are persistent and unquestioned social habits, beliefs, and assumptions, and its ‘derivations,’ which are the explanations, justifications, and rationalizations we make of them. One of the commonest errors of social thinkers is to assume rationality and logic in social attitudes and structures; another is to confuse residues and derivations.”

Fascism and power distribution

Renato Cirillo wrote that Vilfredo Pareto had frequently been considered a predecessor of fascism as a result of his support for the movement when it began. However, Cirillo disagreed with this interpretation, suggesting that Pareto was critical of fascism in his private letters.

Pareto argued that democracy was an illusion and that a ruling class always emerged and enriched itself. For him, the key question was how actively the rulers ruled. For this reason, he called for a drastic reduction of the state and welcomed Benito Mussolini’s rule as a transition to this minimal state so as to liberate the “pure” economic forces.

When he was still a young student, the future leader of Italian fascism Benito Mussolini attended some of Pareto’s lectures at the University of Lausanne in 1904. It has been argued that Mussolini’s move away from socialism towards a form of “elitism” may be attributed to Pareto’s ideas. Franz Borkenau, a biographer, argued that Mussolini followed Pareto’s policy ideas during the beginning of his tenure as prime minister.

Karl Popper dubbed Pareto the “theoretician of totalitarianism”, but, according to Renato Cirillo, there is no evidence in Popper’s published work that he read Pareto in any detail before repeating what was then a common but dubious judgement in anti-fascist circles.

Economic concepts

Pareto Theory of Maximum Economics

Pareto turned his interest to economic matters, and he became an advocate of free trade, finding himself in conflict with the Italian government. His writings reflected the ideas of Léon Walras that economics is essentially a mathematical science. Pareto was a leader of the “Lausanne School” and represents the second generation of the Neoclassical Revolution. His “tastes-and-obstacles” approach to general equilibrium theory was resurrected during the great “Paretian Revival” of the 1930s and has influenced theoretical economics since.

In his Manual of Political Economy (1906) the focus is on equilibrium in terms of solutions to individual problems of “objectives and constraints”. He used the indifference curve of Edgeworth (1881) extensively, for the theory of the consumer and, another great novelty, in his theory of the producer. He gave the first presentation of the trade-off box now known as the “Edgeworth-Bowley” box.

Pareto was the first to realize that cardinal utility could be dispensed with, and economic equilibrium thought of in terms of ordinal utility – that is, it was not necessary to know how much a person valued this or that, only that he preferred X of this to Y of that. Utility was a preference-ordering. With this, Pareto not only inaugurated modern microeconomics, but he also demolished the alliance of economics and utilitarian philosophy (which calls for the greatest good for the greatest number; Pareto said “good” cannot be measured). He replaced it with the notion of Pareto-optimality, the idea that a system is enjoying maximum economic satisfaction when no one can be made better off without making someone else worse off. Pareto optimality is widely used in welfare economics and game theory. A standard theorem is that a perfectly competitive market creates distributions of wealth that are Pareto optimal.

Concepts

Some economic concepts in current use are based on his work:

The Pareto index is a measure of the inequality of income distribution.

He argued that in all countries and times, the distribution of income and wealth is highly skewed, with a few holding most of the wealth. He argued that all observed societies follow a regular logarithmic pattern:

N = A x m {\displaystyle \ N=Ax^{m}}

where N is the number of people with wealth higher than x, and A and m are constants. Over the years, Pareto’s Law has proved remarkably close to observed data:

The Pareto chart is a special type of histogram, used to view the causes of a problem in order of severity from largest to smallest. It is a statistical tool that graphically demonstrates the Pareto principle or the 80–20 rule.

Pareto’s law concerns the distribution of income.

The Pareto distribution is a probability distribution used, among other things, as a mathematical realization of Pareto’s law.

Ophelimity is a measure of purely economic satisfaction.

Major works

Cours d’Économie Politique Professé a l’Université de Lausanne (in French), 1896–97. (Vol. I, Vol. II)

Les Systèmes Socialistes (in French), 1902. (Vol. I, Vol. II)

Manuale di economia politica con una introduzione alla scienza sociale (in Italian), 1906.

Trattato di sociologia generale (in Italian), G. Barbéra, Florence, 1916. (Vol. I, Vol. II)

Compendio di sociologia generale (in Italian). Florence: Barbèra. 1920. (Abridgement of Trattato di sociologia generale)

with Bo Gabriel Montgomery. Politique financière d’aujourd’hui, principalement en considération de la situation financière et économique en Suisse. Attinger Frères, 1919.

Fatti e teorie (in Italian), 1920. (Collection of previously published articles with an original epilogue)

Trasformazione della democrazia (in Italian), 1921. (Collection of previously published articles with an original appendix)

English translations

The Mind and Society. Translated by Bongiorno, Andrew; Livingston, Arthur. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company. 1935. (translation of Trattato di sociologia generale). (Vol. I, Vol. II, Vol. III, Vol. IV)

Compendium of General Sociology, University of Minnesota Press, 1980 (abridgement of The Mind and Society; translation of Compendio di sociologia generale).

Sociological Writings, Praeger, 1966 (translations of excerpts from major works).

Manual of Political Economy, Augustus M. Kelley, 1971 (translation of 1927 French edition of Manuale di economia politica con una introduzione alla scienza sociale).

The Transformation of Democracy, Transaction Books, 1984 (translation of Trasformazione della democrazia).

The Rise and Fall of Elites: An Application of Theoretical Sociology, Transaction Publishers, 1991 (translation of essay Un applicazione di teorie sociologiche).

Articles

“The Parliamentary Régime in Italy,” Political Science Quarterly, Vol. VIII, Ginn & Company, 1893.

“The New Theories of Economics,” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 5, No. 4, Sep. 1897.

“An Italian View,” The Living Age, November 1922.