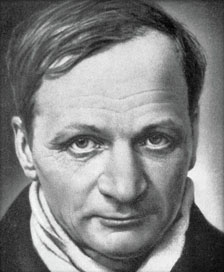

Andrey Platonovich Platonov, real name Klimentov; August 16, 1899, Voronezh, Russian Empire – January 5, 1951, Moscow, USSR) – Russian Soviet writer, poet, publicist, playwright, screenwriter, journalist, war correspondent and engineer. Participant of the Great Patriotic War.

Author of the novels “Chevengur”, “Happy Moscow”, many novels and short stories, including “The Hidden Man”, “Juvenile Sea”, “Epiphanian Locks”, “The Pit”, “In a Beautiful and Furious World”, “Jan”, “ Return”. Platonov is the creator of a unique, well-recognized artistic style.

Andrei Platonovich Klimentov was born on August 16, 1899 (he considered September 1 as his birthday) a mile from Voronezh, in Yamskaya Sloboda. Father – Platon Firsovich Klimentov (1870-1952) worked as a locomotive driver and mechanic in the Voronezh railway workshops. Twice Hero of Labor (1920, 1922), in 1928 he joined the CPSU (b). Mother – Lobochikhina Maria Vasilievna (1874/1875 – 1928/1929) – daughter of a watchmaker, housewife, mother of eleven (ten) children. As the eldest son, Andrei helped raise and feed his many brothers and sisters. Both parents are buried at the Chugunovskoye cemetery in Voronezh.

In 1906, Andrei entered a parochial school. In 1909-1913 he studied at a city 4-grade school. He began writing poetry at the age of 12.

Worked since 1913. He was engaged in minor paperwork in the provincial branch of the Rossiya insurance company. He worked as an assistant driver on a locomotive on the Ustye estate of Colonel Ya. G. Bek-Marmarchev. Since 1915, Platonov’s life has included hard physical labor. He works as a foundry worker at a pipe factory. Manufactures millstones in Voronezh workshops.

Since 1918, he has been collaborating with the Voronezh newspapers Izvestia fortified area and Krasnaya Derevnya. Publishes poems, essays, notes, reviews. Platonov’s first story, “The Next One,” is published in the magazine “Iron Path.”

Army, study

In 1918, Platonov decides to continue his studies and enters the Voronezh University in the physics and mathematics department, but is soon transferred to the historical and philological department.

A year later, the aspiring writer again radically changes his plans and becomes a student in the electrical engineering department of the Voronezh Workers’ Railway Polytechnic. The plans were disrupted by the Civil War. The writer was able to graduate from college only in 1921, after the end of hostilities.

He voluntarily became a participant in the Civil War, where he served as a front-line correspondent. He served in the main revolutionary committee of the South-Eastern Railways, in the editorial office of the magazine “Ironway”.

Since 1919, he published works, collaborating with several newspapers as a poet, publicist and critic. In the summer of 1919, he visited Novokhopyorsk as a correspondent for the newspaper Izvestia of the Defense Council of the Voronezh Fortified Region.

Soon he was mobilized into the Red Army. He serves as an assistant driver on a steam locomotive for military transportation, then as an ordinary rifleman of a railway detachment in a Special Purpose Unit (CHON). He even takes part in battles with the Cossacks.

In 1920 he submitted an application to join the RCP(b). He was recommended by his publisher and member of the presidium of the Gubernia Communist Party Yu. Litvin-Molotov: “I recommend Comrade Klimentov. Platonov is sincere in his writings – he is also sincere in this case, joining our party organization, for he is a real proletarian, a worker, consciously perceiving all phenomena.”

Platonov himself, in his application to join the RCP(b), wrote:

“Our direct natural working path leads me to the Communist Party. I recognized myself as inseparable and united with all the young working humanity growing out of the bourgeois chaos. And for everyone – for the life of humanity, for its merging into one being, in one breath, I want to fight and live. I love the party – it is the prototype of the future society of people, their unity, discipline, power and collective labor conscience; she is the organizing heart of resurrected humanity. Andrey Klimentov (Platonov).”

He was accepted into the party. The “Voronezh Commune” reported this on August 7 in the “Party Life” section. The surname Klimentov (Platonov) was listed first on the list “for approval as a candidate of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks).” He was enrolled as a cadet at the provincial Soviet-party school.

Nevertheless, the young man was soon expelled due to a quarrel with the cell secretary. In addition, he lost his patron: Litvin-Molotov was transferred from Voronezh to Krasnodar, this deprived Platonov of friendly support. It turned out to be difficult for him to maintain party discipline – he missed meetings. And on October 30, 1921, he was expelled. Then he submitted applications several times with a request to be reinstated in the ranks of the party.

At this time, he meets his future wife Maria Kashintseva. He was known in the literary and journalistic community, she had recently entered the philology department. The romance developed rapidly: already in April of the next year they begin to live together, and in September their son Plato is born. From the very beginning, the writer insisted on an official marriage, but they got married more than twenty years after they met, in May 1943. Andrei and Maria Platonov lived together until his death. His wife served as a literary secretary and contributed to the return of Platonov’s name to Russian literature.

Platonov writes a lot. In 1921, his first brochure, Electrification, was published. And after graduating from college, Platonov calls electrical engineering his main specialty. His poems were published in the collective collection “Poems”. A book of his poems, “Blue Depth,” is being published in Krasnodar. The poet Bryusov spoke positively about her.

Working as an engineer. Moving to Moscow

The future writer works on the land. The Voronezh land is black earth, there are great hopes for it: it should feed the young Soviet state.

Shocked by the news of mass famine in the Volga region, in 1922 Platonov entered the service of the Voronezh Provincial Land Administration and headed the provincial Commission for Hydrofication. In a few years, the province will have 763 ponds, 315 mine wells, 16 tube wells and 3 rural electric power plants. Platonov looked for funds to purchase the necessary equipment and encouraged enthusiasts who selflessly worked “waist-deep in the swamp.”

In 1923-1926 he was both a land reclamation engineer and a specialist in agricultural electrification. He headed the electrification department and supervised the construction of three power plants, one of them in the village of Rogachevka was later burned by fists.

Platonov puts forward rationalization proposals: projects for hydrofication of the region, plans to insure crops against drought. He voiced proposals in the spring of 1924 at the First All-Russian Hydrological Congress.

Then he again asks to be accepted into the ranks of the RCP (b). He’s writing:

“I was in the Bolshevik party, went through a purge and left on my own statement, not getting along with the cell. In the statement, I indicated that I did not consider myself to have left the party and did not cease to be a Marxist and communist. I just don’t consider it necessary to perform the duties of attending meetings where Pravda articles are poorly commented on. I consider it more necessary to work on the actual construction of the elements of socialism, in the form of electrification, on the organization of new forms of community life. Meetings must be turned into sincere, constant, working and human communication of people professing the same view of life, struggle and work. I believe that such an act of mine was negative, I personally considered it obligatory for everyone, I now repent of this childish step and do not want to minimize it or hush it up. I made a mistake, but I won’t make any more mistakes.” However, he was denied reinstatement – both this time and subsequent ones.

In June 1925, Platonov first met with the writer Viktor Shklovsky – he flew to Voronezh to promote the achievements of Soviet aviation with the slogan “Facing the Village.”

At the First All-Russian Land Reclamation Conference in Moscow (1926), Platonov was included in the Central Committee of the Trade Union of Forest and Land Workers.

In June 1926, 26-year-old Platonov moved to Moscow with his wife and son; the family received a room in the Central House of Specialists, Bolshoi Zlatoustinsky Lane, 6.

For four months (December 1926 – March 1927) Platonov worked in Tambov without his family. There he creates the “Epiphanian Gateways”, “Ethereal Route”, “City of Grads”. He writes about his work to his wife Maria:

“I live poorly. Reduced more than 50% of its staff. There is a howl. Everyone hates me, even senior engineers (old bureaucrats who have long lost the habit of building). I scatter the remains of the technicians throughout the village wilderness. I expect either a denunciation against myself, or a brick on the street. I left many without work and, probably, without a piece of bread. But I acted wisely and as a pure builder. And there was dirt, ugliness, loafing, whispering. I made the air much healthier. I will long be remembered here as a beast and a cruel person. Where do they treat me better? Who deserved to be treated differently from me? I have one relief – I acted completely impartially, solely from the point of view of the benefits of construction. I don’t know anyone here and have no connections with anyone.” (From a letter to his wife Maria. Tambov, January 28, 1927)

The summer of 1927 was a time of hope for the writer. The June issue of the magazine “Young Guard” publishes the story “Epiphanian Gateways”. A collection of short stories of the same name will be published as a separate book. Platonov hopes to get a job at SovKino. The draft film script based on the story “The Sandy Teacher” is receiving positive reviews. However, reality will differ from expectations. Platonov will not get a job at Sovkino; the production of the film will drag on for years. Books prepared by the writer for publication will not be published. And in the fall of 1927, Platonov’s family was evicted from the Central House of Agriculture and Forestry Specialists. They move to Maria’s father in Leningrad. Despite all this, Platonov is enthusiastically working on the novel “Chevengur”.

In 1927-1930, Platonov created the famous stories “The Pit” and the novel “Chevengur”, which were published in 1985-1987 in magazines of the Perestroika era. Innovative in language and content, the works depict the construction of a new communist society in a fantastic spirit. None of them were published during the writer’s lifetime.

Maxim Gorky treated Platonov warmly and supported him more than once. In 1929, the Soviet classicist read “Chevengur” in manuscript, which seemed “extremely interesting” to him (though he doubted that they would decide to publish it). In the fall of 1929, Maxim Gorky, in response to a letter dated September 21, wrote to Platonov:

“In your psyche,” as I perceive it, “there is an affinity with Gogol. Therefore: try yourself on comedy, not drama. Do not be angry. Don’t worry… Everything will pass, only the truth will remain.”

1930s: devastating criticism. Son’s arrest

Platonov conducts active scientific and literary work. Despite this, living conditions remain difficult, “no room, no money, clothes are worn out.”

Literary workers from RAPP or those close to the proletarian sector recoiled from it after the story “Doubting Makar” (in the magazine “October”). This is taken advantage of by “fellow travelers” grouped around the publishing house “Federation”. Playing on his indignation against writers who are weaker than him creatively, but who live better than Platonov in everyday life, the “fellow travelers” try to secure the writer in their camp.

Being in deep depression, Platonov wrote the story “For Future Use” in 1931, which was published by Alexander Fadeev, editor of the magazine “Krasnaya Nov”. Having touched upon the painful questions of the first five-year plan in the genre of satire, the writer did not give clear answers to them.

The story is sharply criticized by Stalin himself. The leader noted the “gibberish” language and “buffoonery” of the story, as well as the satirical portrayal of the leaders of the collective farm movement. Stalin sent a letter to the editors of Krasnaya Novya, where he described the work as “a story by an agent of our enemies, written with the aim of debunking the collective farm movement.” Stalin demands that the author and publisher be punished in a postscript: “We should punish both the author and the bunglers [who published the story] so that the punishment would benefit them.”

Fadeev, in order to correct the mistake, writes a devastating article in Izvestia, “About one kulak chronicle.” Literaturnaya Gazeta, Pravda and other publications publish revealing articles in which the writer is called a “class enemy” and a “literary subkulak”. In the following years, Platonov, who actually found himself in literary isolation, was almost never published; publishing houses terminated contracts with him.

Platonov resorts to extreme measures – he writes letters of repentance to the editors of Literaturnaya Gazeta and Pravda and to Stalin himself. On June 8, 1931, Platonov wrote a letter to Stalin explaining his position and assuring that he had realized the mistake:

“…After re-reading my story, I changed my mind a lot; I noticed in her something that was imperceptible to me during the period of work and obvious to every proletarian person – the spirit of irony, ambiguity, false stylistics… Knowing that you are at the head of this policy, that in it, in the policy of the party, lies concern about millions, I leave aside all concern for my personality and try to find a way to reduce the harm from the publication of the story “For Future Use.”

Stalin entrusted the “re-education” of Platonov to Gorky. On July 24, Platonov writes to Gorky:

“I cannot become a class enemy, and it is impossible to bring me to this state, because the working class is my homeland, and my future is connected with the proletariat. I say this not for the sake of self-defense, not for the sake of disguise – this is really the case.”

Rejecting accusations of cunning and deceit, the writer admitted that, artistically, the story “For Future Use” is a “minor” text. A personal meeting with Gorky never took place at that time: the literary environment, with indifferent silence or aggressive attacks (which would be repeated again in the late thirties and late forties), gave a clear answer to the question whether Platonov “could be a Soviet writer.”

Later, with the help of Fadeev, who sought to make amends, Platonov and his family settled in the wing of the “Herzen House”, where they would live in two rooms for the remaining twenty years of his life. The plays “Death Announcement” (“High Voltage”, 1932, published 1984), “14 Red Huts” (1932, published 1988), “Lyceum Student” (1948, published 1974) and “Noah’s Ark” were written here. (1950, published 1993), the stories “The Juvenile Sea” (1932, published 1986) and “Jan” (1935, published 1966), the novels “Happy Moscow” (1936, published 1991) and “Journey from Leningrad to Moscow in 1937″ (1937, manuscript lost), the stories “The Inanimate Enemy” (1943, published 1965) and “Aphrodite” (1946, published 1962).

Soon, the RAPP, which criticized Platonov, was itself criticized for excesses and dissolved. Stalin showed his interest in Platonov in 1932. On October 26, the leader came to Gorky’s apartment to meet with leading literary authors. It was there that he called Soviet writers “engineers of human souls.” And the first thing Stalin asked was: “Is Platonov here?”

In 1934, thanks to the support of Gorky, Platonov was included in a collective writing trip to Central Asia: this was a sign of trust. From Turkmenistan the writer brought the story “Takyr”, the story “Jan” and other works. In 1936, the stories “Fro”, “Immortality”, “Clay House in the District Garden”, “The Third Son”, “Semyon” were published, in 1937 – the story “The Potudan River”.

At this time, Platonov collaborated with the famous philosopher György Lukács and also with the critic Mikhail Lifshitz. This is the period of their joint work in the magazine “Literary Critic” and Platonov’s connection with the circle or, as the participants themselves called it, the Lukács-Lifshitz movement. Platonov was included in the philosophical discussions about alienation and freedom that were going on in the current.

In January 1937, during the trial of the so-called “parallel Trotskyist center”, even before the verdict was pronounced, A.P. Platonov published an article “Overcoming Villainy” in the Literary Gazette, in which he justified the need for a death sentence for the defendants:

Is there any organic, calorific principle in the “soul” of Radek, Pyatakov or other criminals? Can they really be called people, even in the elementary sense? No, this is already something inorganic, although deadly poisonous, like the corpse poison from a monster. How do they bear themselves? One, however, couldn’t stand it—Tomsky. Destroying these special villains is a natural, vital task. The life of a working man in the Soviet Union is sacred, and whoever kills it will no longer have to breathe. 〈…〉 Could we, writers, predict the appearance in our books or simply discern such “packaged” villains as the Trotskyists? Yes, they could, because quite a long time ago J.V. Stalin identified them as the vanguard of the counter-revolutionary bourgeoisie. 〈…〉 In short, we need great anti-fascist literature as a defensive weapon.

In the thirties, close acquaintances of the writer were arrested – S. Budantsev, A. Novikov, B. Pilnyak, G. Litvin-Molotov. In May 1938, Platon’s 15-year-old son was arrested. The reason for the arrest, according to one version, was youthful self-indulgence. Plato and a friend wrote a letter to a German journalist who lived next door in the same house with an offer to buy important “information.” According to another version, he was arrested following a denunciation by a classmate (they were both in love with the same girl).

The NKVD authorities reacted quickly, taking advantage of unexpected incriminating evidence on Andrei Platonov. In September 1938, Platon Platonov was convicted and sentenced to ten years in forced labor camps. The writer’s son was sent to serve his sentence in Norillag. To free his son from prison, Platonov wrote letters to Stalin, People’s Commissar of Internal Affairs Nikolai Yezhov and his deputy Mikhail Frinovsky, USSR Prosecutor Mikhail Pankratyev and Chairman of the Supreme Court of the USSR Ivan Golyakov.

In October 1940, the son returned from prison after the efforts of Platonov’s friends and thanks to the assistance of Mikhail Sholokhov, but was terminally ill with tuberculosis. In the summer of 1942, we managed to get our son into a sanatorium, but the treatment did not help. In January 1943, Platon Platonov died.

War correspondent

During the Great Patriotic War, already in August 1941, the writer volunteered to go to the front as a private. But he soon became a military journalist, with the rank of captain in 1942 serving as a correspondent for the newspaper “Red Star”. Platonov – participant in the defensive period of the Battle of Moscow; in December he was presented with the award “For the Defense of Moscow”. Platonov’s stories appear in print. His first war story, “Armor,” was published in September 1942. He talked about a sailor who invented a composition for heavy-duty armor. After his death, it becomes clear: armor, “new metal,” “hard and viscous, elastic and tough” is the character of the people.

Themes of Platonov’s military works: military labor and the feat of the Russian soldier, depiction of the anti-human essence of fascism. Red Star editor-in-chief David Ortenberg recalled: “He was fascinated not so much by the operational affairs of the army and navy, but by people. He absorbed everything he saw and heard through the eyes of an artist.”

Four of his books were published during these years. The war stories “Spiritualized People”, “Recovery of the Dead”, “No Death!”, “Towards the Sunset”, as well as the story “Aphrodite” – a deep reflection on one’s own fate and era – are becoming very famous.

At the front, Platonov is modest in everyday life, spends a lot of time on the front line among the soldiers, and participates in battles. In addition to the Battle of Moscow, Platonov fought in the Battle of Rzhev, as part of the Voronezh Front on the southern flank of the Kursk Bulge in a tank brigade, showed heroism on the Prokhorovsky field on July 12, 1943, served in Ukraine and partisans in the Belarusian forests near Gomel. He conscientiously performed the duties of a military correspondent and risked his life more than once. Quote from a letter to his wife:

“I’m near Kursk. I watch and experience the strongest air battles. One day I went on an adventure. The Germans raided one station. Everyone left the train, me too. Almost everyone lay down, I didn’t have time and stood looking at the flares. Then I didn’t have time to lie down; my head hit a tree, but my head survived. It ended with a headache for two days, which never hurts me, and bleeding from the nose. Now all this has passed; the blast wave was weak for my death. Only a direct hit to the head will kill me.” June 6, 1943.

At the end of the war, he was awarded a second medal – the medal “For Victory over Germany.” During the war, Platonov was awarded the rank of major.

Towards the end of the war, Platonov’s health deteriorated sharply. After the bombing near Lvov in the summer of 1944, a cavity formed in the lungs and tuberculosis began. He did not pay attention to the cough, fever, and elevated temperature, and continued to go to the fronts. In the fall of 1944, Red Star received a telegram: “Platonov has fallen ill. It’s been lying for the last few days. Can’t work. How to proceed?”

However, the writer found the strength to return to writing stories and created a number of brilliant portraits of Soviet officers. At the same time, his daughter Maria was born – “dear Khy” and “little Muma,” as he affectionately called her in letters of 1945 on the southern coast of Crimea, where he was then being treated. In February 1946, the writer was demobilized due to illness.

Last years

Bedridden by a progressive illness, Platonov did not stop working: after the war, Russian and Bashkir folk tales were published in his retellings. He wrote the plays “Pushkin at the Lyceum”, “Noah’s Ark”, seven film scripts, several stories about children and original fairy tales published in children’s publishing houses. The writer’s archive contains the novel “Happy Moscow,” unfinished since the 1930s.

In 1946, his story “Return” (author’s title “Ivanov’s Family”) was published. The critic Ermilov accused the author of “vulgarity” and “the most vile slander against the Soviet people, the Soviet family, and the victorious soldiers returning home.” Alexander Fadeev joined the criticism, who in Pravda called “Ivanov’s Family” “a deceitful and dirty storyteller” and “philistine gossip creeping onto the pages of the press.” On the contrary, Konstantin Simonov, who published the story, wrote: “As for the story “Ivanov’s Family,” Krivitsky and I really liked it. We wanted to publish Platonov, a comrade from Red Star, in the first issue we published.” Konstantin Simonov condemned the critic Ermilov for persecuting the front-line soldier Platonov: “Before this, I firmly, firmly did not like or respect Ermilov. The article was merciless, the blow was inflicted on a defenseless person who had just gotten back on his feet.” Ermilov in 1964, answering the question of critic V. Levin: “Have you had any works that you consider erroneous and would like to cross out?”, replied: “I was not able to enter into the originality of Platonov’s artistic world, to hear his special poetic language , his sadness and his joy for people. I approached the story with standards that were far removed from the real complexity of life and art.”

Subsequently, Platonov managed to publish several reviews, a couple of stories in the magazine Ogonyok, and several collections of folk tales in literary adaptation. His last lifetime publication was the book of Russian fairy tales “The Magic Ring” (under the general editorship of Mikhail Sholokhov, who helped Platonov at that time), which was published several months before the writer’s death.

Andrei Platonov died on January 5, 1951 in Moscow from tuberculosis. He was buried at the Armenian cemetery, behind the Krasnopresnenskaya outpost, next to his son.

After his death, an obituary was published in Literaturnaya Gazeta, ending with the words of farewell: “Andrei Platonov was closely connected with the Soviet people. He dedicated the strength of his heart to him, gave him his talent.” The text was signed by all the main writers of that time: A. Fadeev, M. Sholokhov, A. Tvardovsky, N. Tikhonov, K. Fedin, P. Pavlenko, I. Erenburg, V. Grossman, K. Simonov, A. Surkov, K. Paustovsky, M. Prishvin, B. Pasternak, A. Krivitsky and many others.

Posthumous publication of books

Daughter Maria Platonova (1944-2005) prepared her father’s books for publication. Thanks to her efforts, “Chevengur” and “The Pit,” “Juvenile Sea” and “14 Red Huts” saw the light of day for the first time in Russia. Thanks to her care at the Institute of World Literature. Gorky, where she worked since 1992, the group of Collected Works of Andrei Platonov was formed, the unique “Notebooks” of the writer were published, volumes of the scientific Collected Works were prepared and published.

Awards

Medal “For victory over Germany in the Great Patriotic War of 1941-1945”

Medal “For the Defense of Moscow”

Works

Novels

1929 – “Chevengur” (in the first edition – “Builders of the Country”, 1927)

1933 – “Technical Novel” (not finished)

1933 – 1936 – “Happy Moscow[de]” (not finished)

1936 – “Macedonian Officer” (not finished)

1937 – “Journey from Leningrad to Moscow” (not finished, manuscript lost)

Stories

1926 — “Epifansky locks”

1927 – “City of Grads”, “The Hidden Man”, “Ethereal Route”, “Yamskaya Sloboda” (published – 1927)

1930 – “Pit”

1931 — “For future use”

1932 — “Bread and Reading”

1934 – “Garbage Wind”, “Juvenile Sea”, “Jan[en]”

1937 — “Potudan River”

1944 — “The Gift of Life”

Stories

1920 — “Chuldik and Epishka”

1921 — “Markun”

1926 – “Anti-sexus”, “The Motherland of Electricity”

1927 – “Yamskaya Sloboda”, “Sandy Teacher”, “How Ilyich’s Lamp Was Lighted”

1929 – “State Resident”, “Doubting Makar”

1934 – “Takyr”

1936 – “The Third Son”, “Immortality”

1937 – “In a Beautiful and Furious World”, “Fro”

1938 – “July Thunderstorm”

1939 — “Across the Midnight Sky”

1941 — “The Iron Old Woman”

1942 – “Under the skies of the motherland” (collection of stories), published in Ufa

1942 — “Spiritualized People” (collection of stories)

1943 – “Stories about the Motherland” (collection of stories)

1943 — “Armor” (collection of stories)

1945 – collection of stories “Towards the Sunset”, story “Nikita”

1946 – “Ivanov’s Family” (“Return”)

“Inanimate Enemy”, story

“War” (in manuscript without autodating; approximately 1927)

“Comrade of the Proletariat” (in manuscript without autodating; approximately 1929)

Plays

1928 — “Fools on the Periphery”

1930 – “Hurdy Organ”

1931 – “High Voltage”, “14 Red Huts”

1944 — “Magical Creature”

1948 — “Lyceum Student”

1951 — “Noah’s Ark” (unfinished mystery play)

Other

1921 – brochure “Electrification”

1922 – book of poems “Blue Depth”

1928 – essay “Che-Che-O” (co-authored with B. A. Pilnyak)

1939 – book “Nikolai Ostrovsky” (not published)[48]

1947 – books “Finist – Clear Falcon”, “Bashkir Folk Tales”

1950 – “The Magic Ring” (collection of Russian folk tales)

Platonov Andrey Platonovich

Platonov Andrey Platonovich

(1899—1951s)