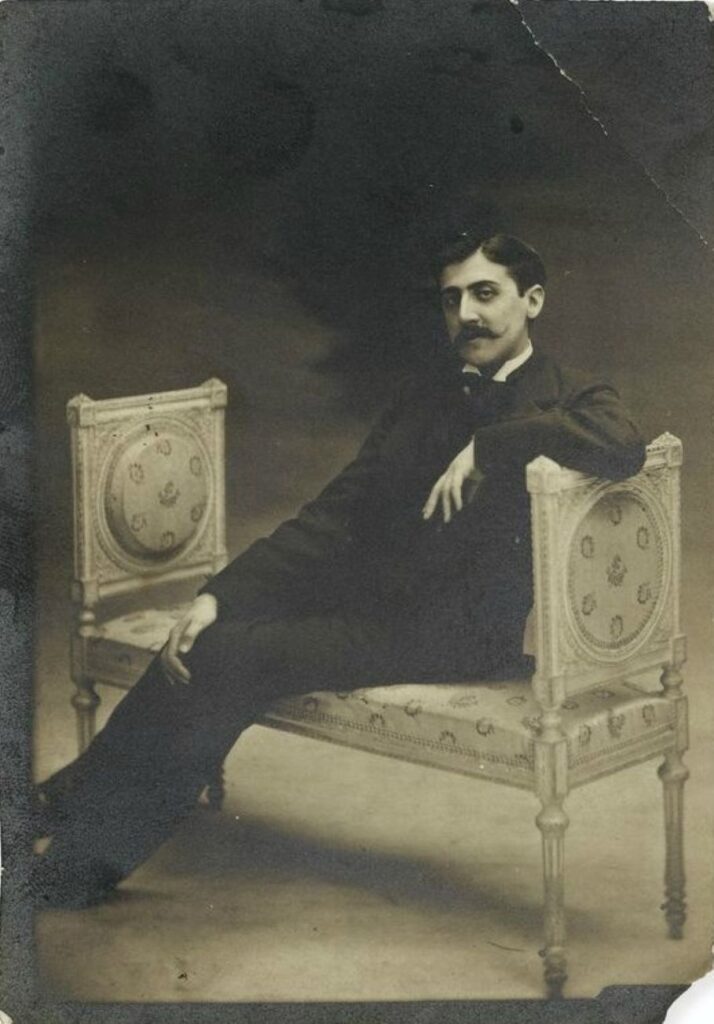

A Young Girl’s Confession, Marcel Proust

A Young Girl’s Confession

The cravings of the senses carry us hither and yon, but once the hour is past, what do you bring back? Remorse and spiritual dissipation.

You go out in joy and you often return in sadness, so that the pleasures of the evening cast a gloom on the morning.

Thus, the delight of the senses flatters us at first, but in the end it wounds and it kills.

—THOMAS À KEMPIS: IMITATION OF CHRIST, BOOK I, CHAPTER 18

Amid the oblivion we seek in false

delights,

The sweet and melancholy scent of lilac

blossoms

Wafts back more virginal through our

intoxications.

—HENRI DE RÉGNIER: SITES, POEM 8 (1887)

At last my deliverance is approaching. Of course I was clumsy, my aim was poor, I almost missed myself. Of course it would have been better to die from the first shot; but in the end the bullet could not be extracted, and then the complications with my heart set in. It will not be very long now. But still, a whole week! It can last for a whole week more!—during which I can do nothing but struggle to recapture the horrible chain of events.

If I were not so weak, if I had enough willpower to get up, to leave, I would go and die at Les Oublis, in the park where I spent all my summers until the age of fifteen. No other place is more deeply imbued with my mother, so thoroughly has it been permeated with her presence, and even more so her absence. To a person who loves, is not absence the most certain, the most effective, the most durable, the most indestructible, the most faithful of presences?

My mother would always bring me to Les Oublis at the end of April, leave two days later, visit for another two days in mid-May, then come to take me home during the last week of June. Her ever so brief visits were the sweetest thing in the world and the cruelest. During those two days she showered me with affection, while normally quite chary with it in order to inure me and calm my morbid sensitivity.

On both evenings she spent at Les Oublis she would come to my bed and say good night, an old habit that she had cast off because it gave me too much pleasure and too much pain, so that, instead of falling asleep, I kept calling her back to say good night to me again, until I no longer dared to do so even though I felt the passionate need all the more, and I kept inventing new pretexts: my burning pillow, which had to be turned over, my frozen feet, which she alone could warm by rubbing them. . . .

So many lovely moments were lovelier still because I sensed that my mother was truly herself at such times and that her usual coldness must have cost her dearly. On the day she left, a day of despair, when I clung to her dress all the way to the train, begging her to take me back to Paris, I could easily glimpse the truth amid her pretense, sift out her sadness, which infected all her cheerful and exasperated reproaches for my “silly and ridiculous” sadness, which she wanted to teach me to control, but which she shared.

I can still feel my agitation during one of those days of her departures (just that intact agitation not adulterated by today’s painful remembrance), when I made the sweet discovery of her affection, so similar to and so superior to my own. Like all discoveries, it had been foreseen, foreshadowed, but so many facts seemed to contradict it!

My sweetest impressions are of the years when she returned to Les Oublis, summoned by my illness. Not only was she paying me an extra visit, on which I had not counted, but she was all sweetness and tenderness, pouring them out, on and on, without disguise or constraint.

Even in those times when they were not yet sweetened and softened by the thought that they would someday be lacking, her sweetness and tenderness meant so much to me that the joys of convalescence always saddened me to death: the day was coming when I would be sound enough for my mother to leave, and until then, I was no longer sick enough to keep her from reviving her severity, her unlenient justice.

One day, the uncles I stayed with at Les Oublis had failed to tell me that my mother would be arriving; they had concealed the news because my second cousin had dropped by to spend a few hours with me, and they had feared I might neglect him in my joyful anguish of looking forward to my mother’s visit.

That ruse may have been the first of the circumstances that, independent of my will, were the accomplices of all the dispositions for evil that I bore inside myself, like all children of my age, though to no higher degree.

That second cousin, who was fifteen (I was fourteen), was already quite depraved, and he taught me things that instantly gave me thrills of remorse and delight. Listening to him, letting his hands caress mine, I reveled in a joy that was poisoned at its very source; soon I mustered the strength to get away from him and I fled into the park with a wild need for my mother, who I knew was, alas, in Paris, and against my will I kept calling to her along the garden trails.

All at once, while passing an arbor, I spotted her sitting on a bench, smiling and holding out her arms to me. She lifted her veil to kiss me, I flung myself against her cheeks and burst into tears; I wept and wept, telling her all those ugly things that required the ignorance of my age to be told, and that she knew how to listen to divinely, though failing to grasp them and softening their significance with a goodness that eased the weight on my conscience. This weight kept easing and easing; my crushed and humiliated soul kept rising lighter and lighter, more and more powerful, overflowing—I was all soul.

A divine sweetness was emanating from my mother and from my recovered innocence. My nostrils soon inhaled an equally fresh and equally pure fragrance. It came from a lilac bush, on which a branch hidden by my mother’s parasol was already in blossom, suffusing the air with an invisible perfume. High up in the trees the birds were singing with all their might. Higher still, among the green tops, the sky was so profoundly blue that it almost resembled the entrance to a heaven in which you could ascend forever.

I kissed my mother. Never have I recaptured the sweetness of that kiss. She left the next day, and that departure was crueler than all the ones preceding it. Having once sinned, I felt forsaken not only by joy but also by the necessary strength and support.

All these separations were preparing me, in spite of myself, for what the irrevocable separation would be someday, even if, back then, I never seriously envisaged the possibility of surviving my mother. I had resolved to kill myself within a minute after her death. Later on, absence taught me far more bitter lessons: that you get accustomed to absence, that the greatest abatement of the self, the most humiliating torment is to feel that you are no longer tormented by absence. However, those lessons were to be contradicted in the aftermath.

I now think back mainly to the small garden where I breakfasted with my mother amid countless pansies. They had always seemed a bit sad, as grave as coats-of-arms, but soft and velvety, often mauve, sometimes violet, almost black, with graceful and mysterious yellow patterns, a few utterly white and of a frail innocence. I now pick them all in my memory, those pansies; their sadness has increased because they have been understood, their velvety sweetness has vanished forever.

How could all this fresh water of memories have spurted once again and flowed through my impure soul of today without getting soiled? What virtue does this morning scent of lilacs have that it can pass through so many foul vapors without mingling and weakening? Alas!—my soul of fourteen reawakens not only inside me but, at the same time, far away from me, outside me. I do know that it is no longer my soul and that it does not depend on me to become my soul again. Yet back then it never occurred to me that I would someday regret its loss.

It was nothing but pure; I had to make it strong and able to perform the highest tasks in the future. At Les Oublis, after my mother and I, during the hot hours of the day, visited the pond with its flashes of sunlight and sparkling fish, or strolled through the fields in the morning or the evening, I confidently dreamed about that future, which was never beautiful enough for her love or my desire to please her.

And if not my willpower, then at least the forces of my imagination and my emotion were stirred up inside me, tumultuously calling for the destiny in which they would be realized, and repeatedly striking the wall of my heart as if to open it and dash outside myself, into life.

If, then, I jumped with all my strength, if I kissed my mother a thousand times, running far ahead like a young dog or indefinitely lagging behind to pick cornflowers and red poppies, which I brought her,